Introduction

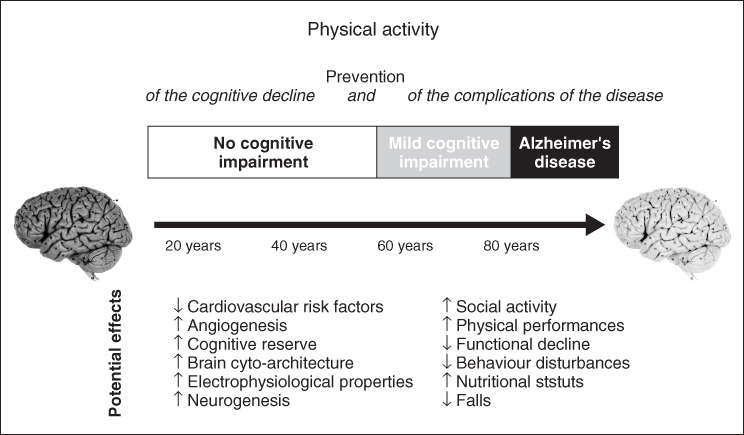

The incidence and prevalence of dementia are expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades. In the absence of curative treatment, risk factor modification remains the cornerstone for dementia prevention. Population studies and randomized controlled trials have recently indicated that people who are cognitively, socially and physically active have a reduced risk of cognitive impairment. Dementia is now considered as a long process resulting from accumulation of both risk and protective factors during lifespan (Figure 77.1).1 Physical activity appears to be one of the main factors that contribute to the maintenance of a healthy ageing brain. Basic research trials also confirmed that an enriched environment and physical activity enhance the proliferation of new brain cells and promote brain repair in animal models.2 Some of the most promising strategies for the prevention of dementia include vascular risk factor control, but also cognitive activity and physical activity.

Physical activity is already known as a cost-effective practice that has demonstrated during the past 30 years numerous physical benefits in the field of heart disease and cancer. The benefits of physical activity on brain functioning have been reported more recently.

Results from clinical and basic research facilitated by new technological approaches such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) support the benefit of physical activity on cognitive decline in humans. However, none of the clinical research has clearly demonstrated that physical activity can prevent dementia. Nevertheless, growing evidence supports the view that physical activity may, at least, slow cognitive decline. Even a small delay of the onset of cognitive decline or a slowing of the disease progression would have a significant impact on this major public health priority.

Physical activity has also been shown to improve function even in frail nursing home residents3 and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients.4 Physical activity yields an important and potent protective factor against functional decline and various frequent and devastating complications of the disease such as falls, fractures, malnutrition and behavioural disturbances, such as depression and anxiety. For demented patients, physical activity may also prevent key problems and have a major impact on the burden of the disease and quality of life.

Physical Activity and The Prevention of Dementia in Clinical Research

Evidence that physical activity prevents cognitive decline is difficult to obtain. Results from epidemiological studies must be considered carefully as numerous biases may influence the relationship between exercise and the risk of dementia: the lifestyle of sedentary participants usually differs from that of exercisers in many ways. Many potential confounders between physical activity and the risk of dementia exist. Moreover, in most epidemiological studies, the assessment of physical activity is questionable. Involvement in physical activity varies substantially during a lifetime. The assessment of physical activity may not correspond to the mean long-term regular activity and even less to activity over the subject’s past lifetime. Conclusions about the impact of different types, intensity and duration of the past physical activity are even more difficult to draw. An important limitation of most epidemiological studies is also that elderly subjects in the preclinical stage of dementia usually reduce their physical activity. Inactivity is a symptom frequently reported in the early phase of dementia rather than a risk factor. Behaviour disturbances such as depression or apathy usually precede the diagnosis of dementia and result in low physical activity. Finally, it is nearly impossible to discriminate between the effects of physical activity per se and the effects related to cognitive stimulation during physical activities that involve cognitive functions. It is therefore difficult to ascertain the specific effects of mobility and energy expenditure on brain functioning.

Despite these limitations, many authors have examined the association between participation in physical activity and cognitive function in large groups of elderly people. Most of the time, the relationship between participation in physical activity and cognitive function is strong. Physically active aged individuals performed better in cognitive tests than their sedentary counterparts, especially in executive tests.5 In several cross-sectional studies, cardiovascular fitness was associated with attention and executive function or visuospatial function. However, the cross-sectional design of these studies precludes inferences about causality in the relationship between physical activity and cognitive function. These cross-sectional studies are also subject to important methodological bias.

Table 77.1 reports most of the longitudinal epidemiological studies published during the past 10 years which have evaluated the association between physical activity and dementia or cognitive decline. Most of these epidemiological studies were controlled for potential confounders and suggest a protective effect of physical activity.

Table 77.1 Observational epidemiological studies on physical activity and risk of dementia or cognitive decline.

| Study | Longitudinal non-demented population-based study | Summary of major findings (adjusted for confounders) |

| Physical activity as a significant preventive factor for dementia | ||

| Hisayama Study (Yoshitake, 1995)6 | 828 individuals aged 65 years or over | Physical activity was associated with reduced risks of AD |

| Paquid study (Fabrigoule, 1995)7 | 2040 individuals aged 65 years or over | Physical activity was associated with reduced risks of dementia |

| Canadian Study of Health and Aging (Laurin, 2001)8 | 6434 individuals aged 65 years or over | High levels of physical activity were associated with reduced risks of cognitive impairment, AD and dementia of any type |

| Health Care Financing Administration Study (Scarmeas, 2001)9 | 1772 individuals aged 65 years or over | Leisure physical activities (walking for pleasure or going for an excursion) were associated with reduced risks of dementia |

| Bronx Aging Study (Yamada, 2003)10 | 469 individuals aged 75 years or over | Dancing was the only physical activity associated with a lower risk of dementia |

| Honolulu–Asia Aging Study (Abbott, 2004)11 | 2257 men aged 71–93 years | Walking more than 2 miles per day was associated with a lower risk of dementia |

| Cardiovascular Health Cognitive Study (Podewils, 2005)12 | 3375 individuals aged 65 years or over | Individuals engaged in more than four physical activities had lower risk of dementia |

| Cardiovascular risk factors, Aging and Incidence of Dementia (CAIDE) (Rovio, 2005)13 | 1449 individuals aged 65–79 years | Leisure-time physical activity, at least twice per week, was associated with a reduced risk of dementia and AD |

| The INVADE Study (Etgen, 2010)14 | 3903 individuals aged 55 years or over | Moderate or high physical activity was associated with a reduced incidence of cognitive impairment |

| Adult Change in Thought (Larson, 2006)15 | 1740 individuals aged 65 years or over | Physical activity at least three times per week was associated with a reduced risk of dementia |

| Physical activity as a non-significant preventive factor for dementia | ||

| Sydney Older Persons Study (Broe, 1998)16 | 327 individuals aged 75 years or over | No statistically significant association between physical activity and dementia |

| Radiation Effect Research Foundation Adult Health Study (Yamada, 2003)10 | 1774 individuals | No statistically significant association between physical activity and dementia |

| Kungsholmen Project (Wang, 2002)17 | 776 individuals aged 75 years or over | Daily physical activity was associated with a no significant reduction risk of dementia |

| Physical activity as a significant preventive factor for cognitive decline | ||

| MacArthur Study (Albert, 1995)18 | 1192 individuals aged 70 to 79 years | Strenuous physical activity was associated with a reduced risk of cognitive decline |

| Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (Yaffe, 2001)19 | 5925 individuals aged 65 years or over | Highest quartile of blocks walked per day was associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline |

| Brescia Study (Pignatti, 2002)20 | 364 individuals aged 70–85 years | Inactivity was associated with a higher risk of cognitive decline |

| Sonoma Study (Barnes, 2003)21 | 349 individuals aged 55 years or over | High peak oxygen consumption (VO2) was associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline |

| Monongahela Valley Independent Elders Survey (MoVIES) (Lytle, 2004)22 | 1146 individuals aged 65 years or over | Exercising five times per week or more was associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline |

| Nurses’ Health Study (Weuve, 2004)23 | 18 766 women aged 70–81 years | Walking at least 1.5 h per week at a pace of 21–30 min per mile was associated with a lower risk of cognitive decline |

| Physical activity as non-significant preventive factor for cognitive decline | ||

| Sydney Older Persons Study (Broe, 1998)16 | 327 individuals aged 75 years or over | No statistically significant association between physical activity and cognitive decline |

Currently, no randomized controlled trial (RCT) has ever concluded that physical activity prevents dementia or AD. Several randomized trials have reported a beneficial effect of a physical exercise programme on the cognitive performances of non-demented participants whereas other randomized trials have reported no cognitive improvement after a physical activity programme. None of these trials were designed to assess incidence of AD or dementia as the main outcome.

In 2003, Colcombe et al.,24 in a meta-analysis of 18 interventional studies with a randomized design published between 1996 and 2001, Christie concluded that there is a significant effect of aerobic exercise training on cognitive function. In a Cochrane review published in 2008, Angevaren et al.25 assessed the effectiveness of physical activity on cognitive function in people older than 55 years of age without known cognitive impairment. Eight out of 11 RCTs that compared aerobic physical activity programmes with any other intervention or no intervention reported an improvement in cognitive capacity that coincided with the increased cardiorespiratory fitness of the intervention group.

Since the above meta-analysis and systematic review, three large RCTs have reinforced these conclusions in non-demented elderly persons but also in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Patients with MCI are known to be at high risk for cognitive decline and AD and may be a target population for prevention programme.

Lautenschlager et al. reported that about 20 min per day of physical activity improved the cognitive function of 170 older adults with MCI.26 The size of the effect of 6 and 18 months of a physical programme was modest but comparable to the benefit usually reported with the use of donepezil. Other authors have also reported that a high-intensity aerobic exercise programme (75–85% of heart rate reserve for 45–60 min per day, 4 days per week for 6 months) results in an improvement of executive control processes in older women with MCI.27

Finally, in the Lifestyle Interventions and Independence for Elders pilot (LIFE-P) study, 102 older adults at risk for mobility disability were randomized to a moderate-intensity physical activity intervention during 1 year. It was reported that the improvements in cognitive scores were associated with improvements in physical function.28

Physical Activity and Executive Function

Most of the epidemiological studies and RCTs support the idea that the effects of physical activity were greatest for those tasks involving executive control processes.24 Physical activity may influence structures and functions of the brain differently than other stimulation such as cognitive stimulation. In the MOBILIZE Boston Study, the neuropsychological executive tests were positively associated with participation in physical activity. In contrast, delayed recall of episodic memory was not associated with physical activity.5 Other studies have reported that aerobic exercise intervention enhances executive function, whereas other cognitive functions seem to be less sensitive or insensitive to physical exercise. Using fMRI, it was recently demonstrated that physical activity enhances plasticity in prefrontal cortical regions that support executive function.29 A physical activity programme also results in an increased grey matter volume mainly in prefrontal and cingulate regions and changes in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) levels.30 Colcombe et al.24 reported that fitter older subjects had a greater grey matter volume in the prefrontal, parietal and temporal regions and a greater white matter volume in the genu of the corpus callosum than their less fit counterparts after controlling for potential confounders. These regions of the brain may retain more plasticity. These results support the notion of a specific biologically determined relationship between executive function and physical activity.

Further research is still required to increase our knowledge regarding the relationship between exercise and cognitive function in humans. However, clinical research and recent research on neuroimaging provide convincing support for the hypothesis that physical activity affects cognitive and neural plasticity in later life and prevents age-related cognitive decline.

Frailty, Physical Activity and Cognitive Reserve

Frailty is a clinical syndrome manifested by weight loss, weakness, fatigue, slow walking speed and low physical activity. These factors diminish the physiological reserves in elderly patients and put them at risk for adverse health outcomes such as disability, hospitalization and death when confronted by a stressor. Frailty has also been reported to be an independent predictor of cognitive decline31 and dementia.32

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree