EVALUATION OF THE INFERTILE COUPLE

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Treating the couple as a unit is important. Although infertility is not lethal, the desire to reproduce is a basic human instinct, and deprivation of fertility may lead to guilt and depression. Because infertility is not a disease and the couple generally are otherwise healthy, they should be encouraged to be active in their evaluation and in determining their course of therapy after 1 year of unprotected intercourse, unless the female partner’s age is 35 years of age or older, she has anovulatory cycles, or she has a history of pelvic pain, pelvic infection, or pelvic surgery. Evaluation of the male partner should be performed early on and he should definitely be evaluated if he has a history of testicular atrophy, testicular injury, undescended testicles, or sexual dysfunction. Most couples are anxious to learn the reason for their infertility even if it cannot be corrected.

Approximately 10% to 40% of couples have more than one cause for their infertility. In the United States, couples seeking evaluation and treatment have limited time as well as limited emotional and financial resources to invest. For these reasons, a comprehensive infertility evaluation should be completed as expeditiously as possible. The couple should be counseled regarding the diagnosis and prognosis, and the treatment alternatives should be presented in an objective, circumspect manner as soon as the tests are completed. When treatment is undertaken, end points should be determined, and periodic reassessment should be anticipated. The decision to terminate therapeutic efforts should be left to the patient; however, after a trial of reasonable duration, continuation of a therapeutic regimen should be discouraged.

The psychological aspects of the diagnosis of infertility and its treatment should be addressed early in the therapeutic alliance, and additional support should be offered to those needing it. The clinical condition of infertility must be presented to the couple as a problem shared by the partners without blaming one individual.

ASSESSMENT OF OVULATION

Ovulatory function spans a spectrum from normal ovulation with optimal reproductive potential to frank anovulation. In between, various degrees of ovulatory dysfunction exist, encompassing entities such as luteal phase deficiency, short luteal phase, and luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome. The first two conditions result from insufficient progesterone production to permit normal endometrial maturational changes and implantation of the embryo, or normal levels of progesterone production that are not sustained long enough to allow complete endometrial maturation.14 Luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome occurs when there is luteinization of the preovulatory follicle and progesterone production, but the ovum is not released from the preovulatory follicle.

The incidence, underlying pathophysiology, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment are controversial for all of these entities. Ovulation most commonly is evaluated by basal body temperature (BBT) charts, which rely on the thermogenic shift induced by pregnanediol, the principal metabolite of progesterone, to indicate the onset and duration of the luteal phase. Such charts lack sensitivity. One large study that measured serum levels of luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), estradiol, and progesterone noted that the time of ovulation was correctly identified by BBT in only 22% of cycles and that 22% of the charts were incorrectly interpreted as showing anovulation.15

Serum progesterone measurement and endometrial biopsy are more reliable methods of assessing ovulatory function. Most laboratories cite a serum progesterone value of 4 to 5 ng/mL as indicative of ovulation and a midluteal value of 10 ng/mL as consistent with normal luteal function. However, progesterone is secreted in a pulsate fashion, and a single value may not reflect luteal function adequately. A midluteal progesterone determination does not depict early or late luteal function, and a single determination may not be sensitive enough to detect subtle luteal dysfunction. Some physicians have proposed using three plasma luteal determinations, with a total value of 15 ng/mL or greater considered consistent with normal luteal function.16

Endometrial biopsy using a dating technique, such as urinary luteinizing hormone predictor kits, has been the traditional

method of evaluating luteal function17 (Fig. 103-1 and Fig. 103-2). Although some subjectivity exists in the interpretation, the test is less expensive than multiple progesterone determinations. However, it is invasive and may require repetition. Moreover, as documented in the original publication, an error in interpretation occurs in 20% to 25% of specimens. The specificity of endometrial biopsy and effectiveness of available treatment remain controversial.

method of evaluating luteal function17 (Fig. 103-1 and Fig. 103-2). Although some subjectivity exists in the interpretation, the test is less expensive than multiple progesterone determinations. However, it is invasive and may require repetition. Moreover, as documented in the original publication, an error in interpretation occurs in 20% to 25% of specimens. The specificity of endometrial biopsy and effectiveness of available treatment remain controversial.

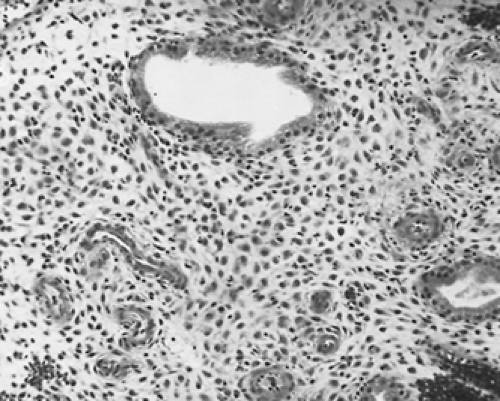

FIGURE 103-2. Endometrial biopsy, representative of day 24 of the menstrual cycle, shows periarteriolar and subcapsular pseudodecidual changes with stromal edema. If this specimen had been obtained the day before menstruation, it would be consistent with luteal-phase deficiency. However, to establish the diagnosis of luteal deficiency, the biopsy findings must be confirmed in two sequential cycles. (Hematoxylin and eosin; ×100)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

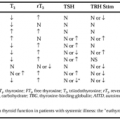

|