Evaluation of Patients for Metastasis Prior to Primary Therapy

Polly Niravath

C. Kent Osborne

After the diagnosis of breast cancer is established, subsequent evaluation for metastatic disease prior to initiation of primary therapy is a somewhat controversial topic. High-quality evidence in this regard is unfortunately lacking; therefore, there is not a common, standardized approach to staging among practitioners in the United States. However, staging clearly does have important implications on both prognosis and treatment. This chapter aims to shed light on the available evidence to support staging for newly diagnosed breast cancer.

The danger of an overly aggressive staging approach is likely greater than the risks of a more judicious staging philosophy. Increased staging examinations impose unnecessary financial expense on the health care system. Especially when considering the sheer number of breast cancer patients, the societal and economic cost of “overstaging” is quite considerable; worldwide, approximately 1.15 million new cases of breast cancer occur each year (1). Furthermore, many staging modalities are likely to lead to “false positives” that result in needless biopsies that pose potential danger to the patient’s health, invoke patient anxiety, increase health care costs, and delay essential treatments.

Currently, in the United States, staging with advanced imaging modalities is becoming more common for early stage breast cancer patients. A review of Medicare records shows that 18.8% of women with stage I or II breast cancer had CT scans, PET scans, and/or brain MRI as part of a staging workup. The use of preoperative staging CT scan increased from 5.7% to 12.4% between 1992 and 2005, and the use of PET scans increased from 0.8% to 3.4% in the same time period. Brain MRI increased from 0.2% to 1.1%, but bone scans actually declined from 20.1% to 10.7% (2). Although the data do not necessarily support staging asymptomatic patients with early stage breast cancer, this practice is clearly increasing in the United States, which leads to increased medical costs and procedures. Also, the use of preoperative CT scans and bone scans have been shown to significantly delay the time from initial breast complaint to the time of breast surgery (3). If the imaging uncovers false positives, delays will, of course, be even longer because biopsies or confirmatory imaging is often ordered as a result of an abnormal staging examination. These delays in the time to surgery represent a needless decrease in the quality of breast cancer care.

INITIAL EVALUATION

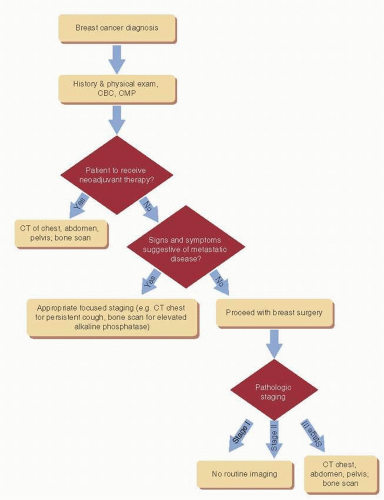

After a patient has had a breast biopsy that establishes the diagnosis of breast cancer, the physician should perform a thorough history and physical exam, including complete review of systems. Routine blood tests, including complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel, should also be done at this time. If the patient appears to have early stage disease and the evaluation discussed does not indicate distant metastatic disease, then there is no need for preoperative advanced staging modalities. However, if a patient does have signs or symptoms of possible metastatic disease, such as weight loss, bone pain, persistent cough, or elevated alkaline phosphatase, appropriate staging studies should be done at the physician’s discretion (see Fig. 31-1).

In the case of patients with locally advanced disease at the time of diagnosis (T2 or larger lesions or palpable lymphadenopathy), neoadjuvant therapy may be an appropriate approach for them. In this case, it would be prudent to obtain staging prior to starting neoadjuvant therapy with CT scan with contrast of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis as well as bone scan.

For those patients who are not receiving neoadjuvant therapy, however, the risk of distant metastasis is better evaluated based on surgical pathologic criteria, such as tumor size and degree of lymph node involvement. Thus, in cases of small breast cancers that are not amenable to neoadjuvant therapy, decisions regarding staging evaluations are best made after surgery because the pathologic stage of the cancer should inform the choice of staging modalities. In this way, many patients with earlier stage disease can be spared unnecessary imaging procedures, and only those with highest risk of disease will receive advanced staging evaluation. Although it is true that some patients with occult metastatic disease may undergo breast surgery prior to discovering the

metastases, there may be some benefit from breast surgery for these patients because retrospective studies have shown increased overall survival in those metastatic patients who have had mastectomy with negative margins at the time of diagnosis (4, 5). However, preliminary data from two randomized trials in Turkey and India suggest that there is no overall survival advantage to mastectomy for metastatic patients (6, 7), but definitive conclusions about the role of surgery in this setting await additional data. In the meantime, surgery to control local disease is also an important endpoint.

metastases, there may be some benefit from breast surgery for these patients because retrospective studies have shown increased overall survival in those metastatic patients who have had mastectomy with negative margins at the time of diagnosis (4, 5). However, preliminary data from two randomized trials in Turkey and India suggest that there is no overall survival advantage to mastectomy for metastatic patients (6, 7), but definitive conclusions about the role of surgery in this setting await additional data. In the meantime, surgery to control local disease is also an important endpoint.

EVALUATION OF THE IPSILATERAL AND CONTRALATERAL BREASTS

At the time of breast cancer diagnosis and prior to breast surgery, each woman should have a bilateral breast exam and mammogram to exclude multicentric disease within the same breast as well as contralateral breast cancer. Depending on the density of the woman’s breast and the discretion of the radiologist, breast ultrasound may also be pursued. Ultrasound also affords the possibility to look at the axillary lymph nodes in greater detail than the mammogram does. Please refer to Chapter 12 for more information regarding the use of breast ultrasound in the diagnosis of breast cancer.

Breast MRI is likely the most sensitive imaging modality for comprehensively evaluating the breasts prior to surgery. A large meta-analysis of more than 2,600 newly diagnosed breast cancer patients discovered that 16% of them were found to have additional foci of malignancy in the affected breast. Furthermore, 11.3% converted from wide local excision (WLE) to more extensive surgery, which may have been wider excision or mastectomy. Specifically, 8.1% of the total

group converted from WLE to mastectomy. Conversely, surgery was changed from WLE to mastectomy because of a false positive in 1.1% of women, and surgery was changed from WLE to more extensive excision in 5.5% of patients for a false-positive finding. In this study, for every three women who were found to have additional lesions on MRI, one of the three proved to be a false positive (8).

group converted from WLE to mastectomy. Conversely, surgery was changed from WLE to mastectomy because of a false positive in 1.1% of women, and surgery was changed from WLE to more extensive excision in 5.5% of patients for a false-positive finding. In this study, for every three women who were found to have additional lesions on MRI, one of the three proved to be a false positive (8).

These risks and benefits are perhaps better weighed when one takes into account the histology of the tumor. It is well known that lobular cancers tend to be more often multicentric and mammographically occult (9). Theoretically, when isolating a high-risk population such as this, the potential benefits of breast MRI may be greater. One retrospective study of 267 breast cancer patients found that 25.5% of patients had more extensive surgery because of preoperative MRI findings. Among these patients, 29% turned out to have had no pathologic verification on surgical specimen to justify the additional surgery. However, when the small subset of lobular carcinoma was studied, 11 of 24 (46%) patients with lobular carcinoma had a change in management because of MRI findings. Furthermore, 9 of these 11 patients had pathologic verification of additional malignancy at the time of surgery, yielding an 82% sensitivity (10). However, it must be noted that ultrasound was not evaluated in this study. In practice, ultrasound is commonly used in conjunction with mammogram to define the extent of disease. Future prospective studies are needed to compare the sensitivity and specificity of combined mammogram and ultrasound to that of breast MRI. Also, it is unknown whether the wider excisions and mastectomies that were prompted by MRI findings would have proven to be clinically relevant. Because almost all women who have lumpectomies will receive adjuvant radiation, it is not known whether the additional surgery truly does lower local recurrence rate as compared to adjuvant radiation. Nonetheless, women with lobular carcinoma may be more likely to have other areas of disease uncovered by MRI, and they are less likely to have false-positive MRI results. Based on the available evidence, breast MRI may be pursued at the physician’s discretion in cases of lobular cancer, particularly in the case of a woman with dense breasts on mammogram or high probability of breast cancer. Please refer to Chapter 13 for more information on breast MRI.

TABLE 31-1 Metastases Discovered from Staging Studies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

BASIC STAGING FOR SYSTEMIC DISEASE (BONE SCAN, LIVER ULTRASOUND, AND CHEST X-RAY)

The scarce data available regarding staging practices in the Unites States reveal that approximately 88% of physicians routinely order staging chest x-rays for all newly diagnosed breast cancer patients, and 39% routinely order bone scans (11). However, the evidence does not support this approach. A systematic review examined the utility of chest x-rays, bone scans, and liver ultrasounds in staging asymptomatic breast cancer patients who have just undergone breast surgery for clinical stage I-III disease (12). The results, among others, are summarized in Table 31-1 (12, 13, 14, 15 and 16). Clearly, the yield of these staging procedures in uncovering metastatic disease is quite low, particularly in stage I and II disease, and especially when weighed against the risk of false positives, which often necessitate biopsies and provoke anxiety. In fact, when reported, the rate of false positives was far higher than the rate of true positives for all three staging examinations in stage I and II patients.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree