The esophagus is a thin-walled, hollow tube with an average length of 25 cm.

The normal esophagus is lined with stratified squamous epithelium similar to the buccal mucosa.

There are many methods of subdividing the esophagus, all of which are arbitrary.

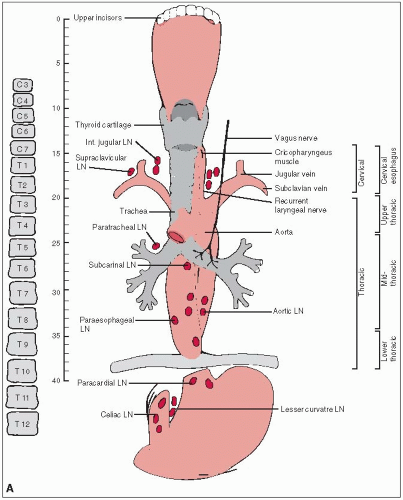

The cervical esophagus begins at the cricopharyngeal muscle (C7) and extends to the thoracic inlet (T3). The thoracic esophagus represents the remainder of the organ, going from T3 to T10 or T11.

The American Joint Committee on Cancer divides the esophagus into four regions: cervical, upper thoracic, midthoracic, and lower thoracic.

Figure 23-1 correlates the basic anatomy of the esophagus with the subdivision schemes described above.

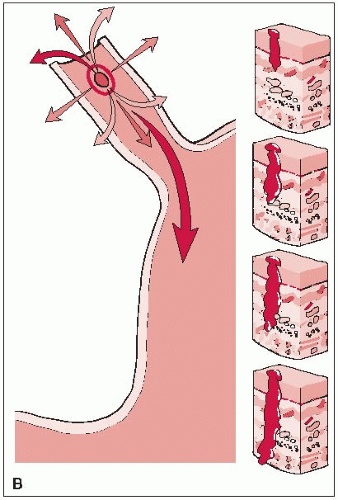

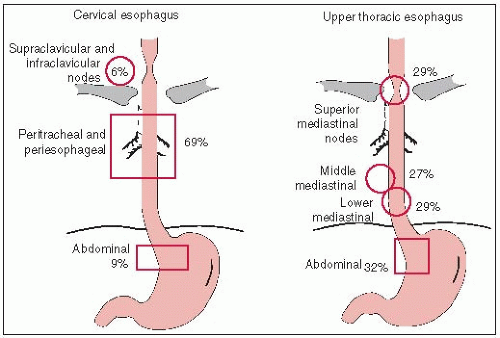

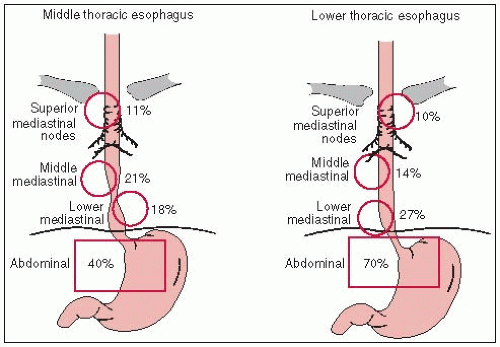

The esophagus has a dual longitudinal interconnecting system of lymphatics. As a result of this system, lymph fluid can travel the entire length of the esophagus before draining into the lymph nodes, so that the entire esophagus is at risk for lymphatic metastasis.

In “skip areas,” up to 8 cm of normal tissue can exist between gross tumor and micrometastasis within lymph fluid traveling in the esophagus (13).

Lymphatics of the esophagus drain into nodes that usually follow arteries, including the inferior thyroid artery, the bronchial and esophageal arteries from the aorta, and the left gastric artery (celiac axis) (27). Figure 23-2 illustrates the major lymph node groups draining the esophagus.

Lymph node metastases are found in about 70% of patients at autopsy.

The estimated incidence of squamous cell cancer in each third of the esophagus is as follows: upper third, 10% to 25%; middle third, 40% to 50%; lower third, 25% to 50% (16, 21).

Achalasia of long duration (≥25 years) is associated with a 5% incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (35). Caustic burns, especially lye corrosion, are related to the development of esophageal cancer (2, 15).

Adenocarcinoma has now surpassed squamous cell carcinoma as the most common histology (7). The incidence of adenocarcinoma has increased 350% since 1970 and now accounts for 75% of all esophageal cancers in Caucasian males.

The condition most commonly associated with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is Barrett’s esophagus.

Symptoms of esophageal cancer usually start 3 to 4 months before diagnosis.

Dysphagia and weight loss are seen in over 90% of patients.

Odynophagia (pain on swallowing) is present in up to 50% of patients.

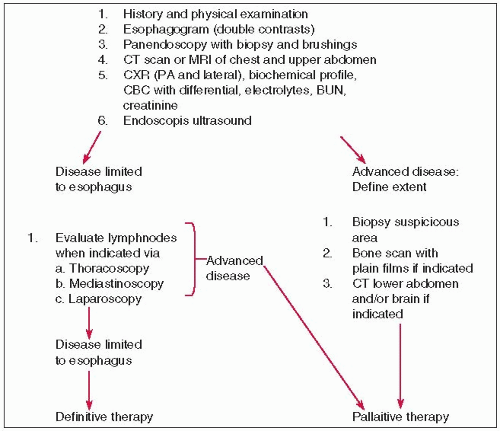

All patients with suspected esophageal cancer should have a workup similar to that outlined in Figure 23-3.

Computed tomography (CT) (9) has an accuracy of 51% to 70% (based on a threshold for malignancy of 10 mm) in the detection of mediastinal nodes in patients with esophageal cancer, and 79% (based on a threshold of 8 mm) in the detection of left-sided gastric or celiac nodes (24). Understaging of disease with CT occurs more frequently than overstaging, increasing the likelihood of inappropriate surgery.

Endoscopic ultrasound is superior for T-staging (sensitivity, 81%; specificity, 67%), and for N-staging (sensitivity, 63%; specificity, 88%) (9).

Most malignant tumors metabolize glucose at a much higher rate than normal tissue; as a result, there is an increased accumulation of the glucose analog fluoro-18 2-deoxyglucose (FDG) in malignant tissue. Positron emission tomography (34) provides diagnostic information based on this increased FDG uptake and often demonstrates early-stage disease before any structural abnormality is evident. PET also can help exclude the presence of malignant disease in an anatomically altered structure.

FDG-PET imaging is superior to CT imaging for evaluating distant metastases (sensitivity, 74%; specificity, 90%) (9).

A number of staging systems have been proposed.

Table 23-1 represents the American Joint Committee on Cancer clinical and pathologic staging system (1). The T stages are illustrated in Figure 23-1B.

TABLE 23-1 AJCC Staging for Cancer of the Esophagus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||