Clinical and Endoscopic Features of Sessile Serrated Polyps

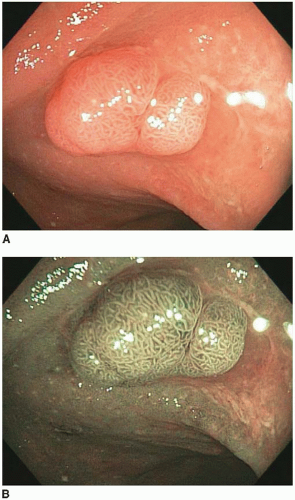

Sessile serrated polyps are nondysplastic polyps that show a predilection for the abdominal colon and, unlike most hyperplastic polyps, are more common among women. These polyps have been termed “serrated polyps with abnormal proliferation,” “giant hyperplastic polyps,” and “sessile serrated adenomas,” but are now classified as “sessile serrated adenomas/polyps” by the World Health Organization in order to avoid confusion with hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas.

16 Sessile serrated polyps represent 2% to 9% of all endoscopically resected polyps and 7% to 21% of all nondysplastic serrated polyps.

7,

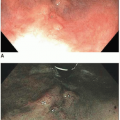

17 Sessile serrated polyps are plaques that merge imperceptibly with the adjacent nonlesional mucosa, and, thus, their size maybe difficult to appreciate endoscopically. They are often covered with a thick layer of mucus and contain round dilated crypts that are visible by chromoendoscopy. A growing body of evidence indicates that these polyps represent precursors to some sporadic colonic adenocarcinomas characterized by a high degree of microsatellite instability (MSI-H). They are believed to confer a biologic risk approaching that of conventional adenomas of comparable size. Thus, screening guidelines parallel those for conventional adenomas with overt dysplasia.

Pathologic Features of Sessile Serrated Polyps

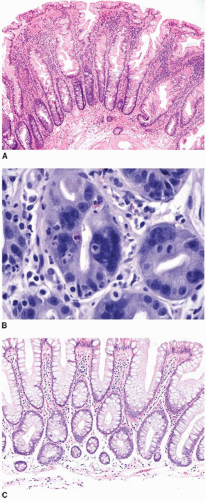

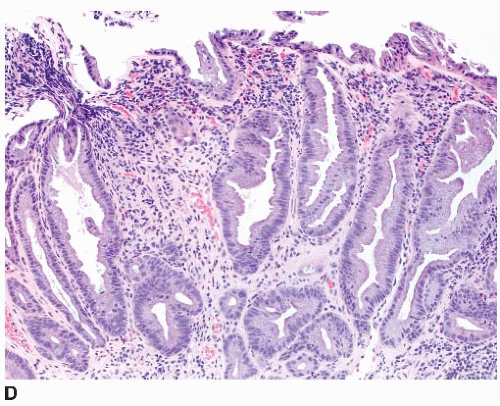

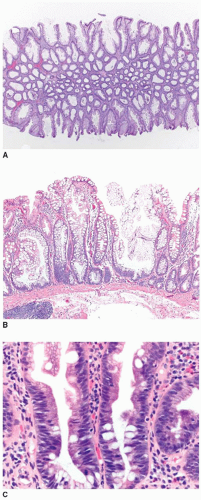

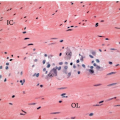

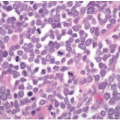

Sessile serrated polyps are broad-based polyps that contain numerous elongated crypts with prominent infolding of the crypt epithelium (

Figure 4.2A). The crypts of a sessile serrated polyp show persistent dilatation at their bases, often with branching or budding above the muscularis mucosae (

Figure 4.2B). The crypts contain variable numbers of goblet cells and nongoblet mucinous columnar cells, similar to hyperplastic polyps, but they tend to show a greater degree of cytologic atypia that extends in an asymmetric fashion from the crypt bases (

Figure 4.2C).

7,

18 Distinction of sessile serrated polyp from hyperplastic polyp is subject to a high degree of interobserver variability, particularly when polyps are smaller than 1 cm in diameter and occur in the left colon. Diagnostic challenges stem from the fact that there are no “hard” criteria for a diagnosis of sessile serrated polyp. Rather, the diagnosis is based on a constellation of seven findings, four or more of which should be present in order to classify a polyp as a sessile serrated polyp (

Table 4.1).

7,

18 Unfortunately, quantifying these features is somewhat subjective, and many are frequently present to a variable extent among small, serrated polyps of the descending colon and rectum, resulting in substantial overlap between the diagnostic criteria for hyperplastic polyp and sessile serrated polyp.

8 Indeed, hyperplastic polyps of the abdominal colon also show immunohistochemical and molecular features that substantially overlap with those of sessile serrated polyps, as discussed subsequently.

19Immunohistochemical and Molecular Features of Sessile Serrated Polyps

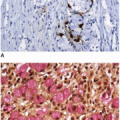

Sessile serrated polyps show Ki-67 nuclear staining of approximately 33% of the nuclei, which is slightly more than hyperplastic polyps, but less than that of conventional adenomas. Ki-67-labeled nuclei are not confined to the basal epithelial cells, but are randomly distributed within the crypts, reflecting abnormal proliferation.

10 Cytokeratin 20 and CDX2 immunostains demonstrate randomly distributed positive cells within the crypts.

10 Sessile serrated polyps show immunostaining for MUC2, MUC5AC, and MUC6.

11,

17,

20 Early studies suggested that MUC6 positivity may be a helpful marker to distinguish between sessile serrated polyps and hyperplastic polyps, but better designed studies have since refuted this notion.

20 MUC6 immunostains are often positive in hyperplastic polyps of the abdominal colon, suggesting that it is a marker of location (i.e., proximal colon) rather than phenotype among serrated polyps.

21Seventy-eight to 100% of sessile serrated polyps harbor

BRAF mutations, whereas

KRAS mutations are uncommon, being observed in less than 10% of cases.

8,

13,

14,

22 These polyps frequently

(60% to 70%) show the CIMP.

14,

22 Loss of MGMT and MLH1 immunoexpression is limited to the superficial epithelial cells, but reflects the nonproliferative nature of the polyp surface, rather than underlying microsatellite instability (MSI). Early investigations reported

MGMT and

MLH1 promoter methylation in 40% and 72% of sessile serrated polyps, respectively.

7,

14,

17,

23 Unfortunately, these studies utilized qualitative, rather than quantitative, assays, and more recent data indicate that sessile serrated polyps are microsatellite stable with preserved MLH1 function.

24