INTRODUCTION AND IMPORTANCE/EXPANDING ROLE OF EPIDEMIOLOGY IN THE HEALTHCARE FACILITIES

The term epidemiology is derived from the Greek

epi (on or upon),

demos (people or population), and

logos (word or reason). Literally, it means “the study of things that happen to people”; historically, it has involved the study of epidemics (

1,

2). The Harvard School of Public Health defines epidemiology as “the study of the frequency, distribution and determinants of disease in humans. Epidemiologists use many approaches, but the ultimate aim of epidemiologic research is the prevention or effective control of human disease.” (

3) For many years, the population for discussion in this text would have been solely/predominately hospitalized patients, and the terms hospital-acquired or nosocomial infection would have been used. Since the spectrum of healthcare and the interaction of different types of healthcare facilities (including hospital, long-term care, rehabilitation, or ambulatory care facilities) have expanded in recent years, a more appropriate term healthcare-associated infections (HAI) will be used in this chapter (still used interchangeably with nosocomial as appropriate) (

4).

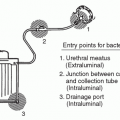

In hospitals alone, HAIs account for an estimated 2 million infections, 90,000 deaths, and $4.5 billion in excess healthcare costs annually (

4,

5). There has been a shift in the patient population that healthcare facilities care for, especially in hospitals, to more complicated patients, including those who are more severely ill (multiple comorbidities and the need for intensive care unit [ICU] level of care) and an increasing number of patients who are severely immunocompromised. More invasive devices and procedures are used in patients and for longer durations of time. In recent cost-conscious times, there have been staffing shortages (decreasing staff to patient ratios). In addition, over several decades, multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) and emerging infectious diseases have developed or increased. All of these have added to the challenge of preventing and controlling HAIs (

6). Even with these challenges, recent data have documented that a much greater proportion of HAIs are preventable than previously estimated. Facilities in many areas have found that using bundled interventions and prevention measures have been able to substantially reduce HAIs such as central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLA-BSIs) (

7,

8).

In recent years, the incidence and severity of

Clostridium difficile infection have increased dramatically. Since 2000, widespread regional outbreaks associated with a previously uncommon hypervirulent strain (B1NAP1) of

C. difficile have occurred in North America and Europe. Most likely because of increased toxin production as well as other virulence factors, this epidemic strain has caused more severe and refractory disease leading to complications, including ICU admission, colectomies, and death (

9). Despite improvements in many other HAIs,

C. difficile continues to be a challenge to the healthcare epidemiology community. It is in this spirit that many healthcare epidemiology professionals have expanded their focus to also promote sensible antimicrobial prescribing through more formal antimicrobial stewardship programs (

10,

11).

The 2009 H1N1 Influenza outbreaks tested the healthcare system, and in many institutions healthcare epidemiology professionals took a lead in response. The surges of patients, testing challenges, isolation challenges, and healthcare worker (HCW) exposures presented a real-time experience in preparation and response to a pandemic and other challenges (

12).

Since the last edition of this text, legislation that obligates hospitals to report specific HAI information has been passed in many states (

13). Professional infection control and healthcare epidemiology organizations and healthcare epidemiologists throughout the United States assisted in framing legislation and helping hospitals how to comply with these legislations (

13,

14,

15). Each state was able to choose the HAIs, specific measures and mechanisms of reporting. Most have adapted

definitions, templates, and reporting via the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) (

13).

In addition, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has created a reportable “hospital-acquired conditions” (HAC) which are quality measures to reduce payments to hospitals for hospital-acquired complications of care. The CMS rule that went into effect in October 2008 stipulated that hospitals would no longer receive additional reimbursement for ten HAC, three of which were HAIs, including ICU CLA-BSIs (

16,

17).

All of these challenges illustrate the important and evolving role that those in infection control and healthcare epidemiology have in healthcare facilities. Although the circumstances may change, it is the working knowledge of the principals of epidemiology and especially of the subtleties that apply to HAI/adverse events that is essential and sets us apart from other HCWs. The healthcare epidemiologist will be the one person who has the skills to analytically review occurrences and design studies to evaluate risk factors and interventions (i.e., wielding the power of epidemiology to impact prevention and control of HAIs).

It is with this in mind that the focus of this chapter is to review the basic principles of epidemiology with special emphasis on the relationship of these to HAIs. This first chapter in earlier editions of this text,

Hospital Infections (

1) had been relatively stable and written by one of the fathers of infectious diseases epidemiology and nosocomial infections. Although much of the basic format of this chapter is unchanged, the author hopes to update this classic chapter including new nomenclature, advanced epidemiological methods and updated examples, and references for the basic epidemiological principals related to HAIs.

EPIDEMIOLOGIC METHODS

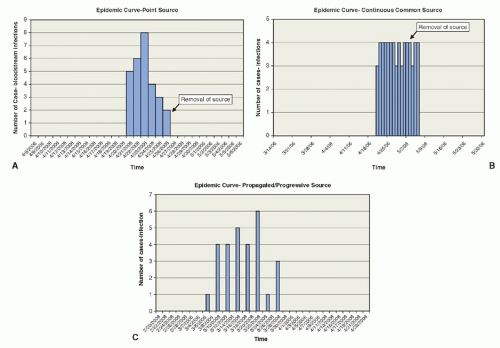

Generally, three techniques are used in epidemiologic studies: descriptive, analytic, and experimental; all may be used in investigating HAIs. Descriptive epidemiology is the foundation for evaluation of HAIs and is used in both surveillance and most investigations of potential problems/outbreaks. Once the

initial problem has been defined by descriptive epidemiology, additional studies using analytic and/or experimental methods can be conducted to develop more information about the problem, confirm initial impressions, prove/disprove hypotheses (including identifying risk factors/potential associations/sources or causes), and evaluate the effectiveness of control measures and/or prevention measures.

The presentation of descriptive epidemiology can include case report/case series. A case report is the clinical description of a single patient. A case series is a report of more than one patient. These types of studies/publications are easy to prepare and can serve as examples to other healthcare epidemiologists. These studies also can serve as a resource to generate hypotheses and ideas for additional studies. The disadvantage of this type of study is that patient numbers are small, and the findings may not be generalizable to other populations. In addition, no comparison to other groups has been made.

The analytic study section will discuss case-control and cohort studies, which are the comparative studies frequently used in healthcare epidemiology, especially to explore outbreaks and healthcare epidemiology problems to identify risk factors and potential associations. Additional analytic-type studies that can be used for healthcare epidemiologic studies are ecologic or cross-sectional studies. Experimental methods of studies include randomized control trials (RCTs; rarely used in healthcare epidemiology) and quasi-experimental studies (to evaluate an intervention without randomization).

DESCRIPTIVE EPIDEMIOLOGY

Descriptive epidemiologic studies evaluate the occurrence of disease in terms of time, place, and person (

1,

38); each “case” of a disease is first characterized by describing these three attributes. When data from the individual cases are combined and analyzed, the parameters of the outbreak or disease problem should be characterized. Issues that arise regarding time, place, and person in general descriptive epidemiology and specifics to healthcare epidemiology are discussed next.