Epidemiology of Colorectal Adenocarcinoma

Karen Curtin

Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide, affecting more individuals in economically developed, affluent nations than in underdeveloped countries. Only a small fraction of colorectal cancers are associated with known genetic syndromes. An estimated 75% to 95% of patients have little or no genetic risk, and most do not have a family history of the disease. Increasing age is strongly associated with colorectal cancer development; evidence suggests that lifestyle and diet may be involved. As the majority of colorectal cancers are sporadic, this chapter focuses on the epidemiology of potentially modifiable factors that have been associated with increasing or decreasing risk of this disease.

Each section of this chapter is based on the most recent information available. Estimates of risk are derived from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of results across dozens of epidemiologic studies published over the past four decades. These cohort-based, case-control, and prospective investigations have been conducted in populations around the globe and thus reflect findings in tens of thousands of individuals collectively. The impact of each factor on colorectal cancer development is portrayed as a percentage of increased or decreased risk at the individual level. Estimates of attributable risk at the population level are also provided.

INCIDENCE AND MORTALITY OF COLORECTAL CARCINOMA

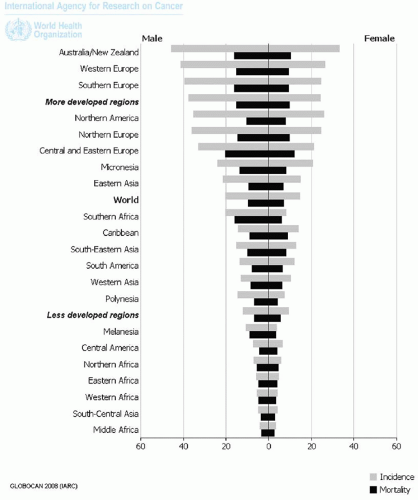

Colorectal carcinoma is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide. There were 1.2 million newly diagnosed cases and 608,000 cancer-related deaths in 2008, making it the fourth most common cause of death from cancer.1,2 Approximately 60% of colorectal cancers are diagnosed in economically developed regions: The highest estimated incidence rates are observed in Australia, New Zealand, and Western Europe. There is less regional variability with respect to colorectal cancer mortality rates. Both incidence and mortality rates are slightly lower in women than in men (Figure 2.1).

Approximately 143,460 individuals (73,420 men and 70,040 women) in the United States have been diagnosed with colorectal cancer, and 51,690 people have died of this malignancy in 2012.3 The age-adjusted incidence rate is an estimated 46.3 per 100,000 individuals per year, and the age-adjusted annual mortality rate is 16.7 per 100,000. These values are based on 2005 to 2009 data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program, National Cancer Institute, U.S. National Institutes of Health (http://seer.cancer.gov), and are based upon findings obtained from specific geographic areas representing 28% of the population.3 Although incidence rates for colon cancer are similar for men and women, rectal cancers occur more often in men.4 Recent declines in colorectal cancer incidence in the United States (2.5% annually from 1998 to 2009) reflect the introduction of colonoscopy as a screening tool in the early 1990s and its widespread use beginning in 2001, which coincided with expanded insurance reimbursement.3,5

Five-year survival rates for colorectal cancer range from 90% for localized cancers to 12% for individuals with metastatic disease.3,6 Stage-independent disparities in survival among regions in the United States and worldwide exist due to differences in access to diagnostic services and treatment. Five-year survival rates have improved significantly over the last few decades in the United States, but death rates continue to be higher among blacks than whites and other racial/ethnic groups (Table 2.1). This disparity in survival has widened in comparison to trends for other cancers.3,6

Table 2.1 Age-Adjusted Colorectal Cancer-Related Death Rates by Race/Ethnicity in the United States, 2005-2009 (per 100,000 Men or Women) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

NONMODIFIABLE RISK FACTORS

Some colorectal cancer risk factors, such as age, history of polyps, and genetic risk, cannot be altered or modified by the individual. Increasing age is strongly associated with increased colorectal cancer incidence: The median age at colorectal cancer diagnosis in the United States is 69 years, and nearly two-thirds of tumors are diagnosed in persons 65 years of age and older, while only 5% are diagnosed before the age of 45 years.3 Colorectal adenomas are precursor lesions of colorectal cancer.7 The lifetime risk of developing a colorectal adenoma may be over 18% in the United States, but detection and removal of polyps before malignant transformation reduces the risk of death from colorectal cancer.8,9 Although hyperplastic polyps have been considered to have little potential for progression to cancer, large nondysplastic serrated polyps (>1 cm) of the abdominal colon are associated with an increased risk of colon cancer, especially if they are multiple, as discussed in Chapters 4,11, and 12.10

Only 5% to 6% of colorectal cancers develop in association with heritable disease.11,12 The most common of these inherited disorders are familial adenomatous polyposis, which results from APC mutations, and Lynch syndrome, which is caused by mutations in DNA repair genes, as discussed in Chapters 11 and 12. Individuals with familial adenomatous polyposis typically develop hundreds of polyps at a young age, and virtually 100% will develop colorectal cancer unless a prophylactic colectomy is performed.13 The lifetime risk of colorectal cancer among patients with Lynch syndrome may be as high as 70% to 80%, but cancers are usually diagnosed in the fifth decade of life, which is later than those associated with familial adenomatous polyposis.4,12

Approximately 20% to 25% of colorectal cancers occur in patients with a family history of colorectal cancer, unassociated with familial adenomatous polyposis or Lynch syndrome. Such tumors are considered familial cancers and are likely due to inheritance of relatively common, low-penetrance genetic variants that portend low to modest cancer risk.11 It is unclear whether familial colorectal carcinomas occur due to an inherited predisposition, shared environmental exposure, or a combination of both. Low-penetrance variants affecting APC, BLM, HRAS1, and TGFβR1 have been described, and recent efforts to uncover additional genetic susceptibility variants have revealed a number of genome-wide associations.11 Genetic variants present in the SMAD7 gene and regions on chromosomes 8q24 and 18q21, all of which are commonly altered in colorectal cancers, have been identified in many people. These variants are associated with a modest (10% to 30%) increased risk in carriers compared with individuals without the variant.14, 15 and 16˜ Other genetic variants in candidate genes interact with diet and lifestyle factors, such as inflammation or insulin-related pathway, and are associated with very modest effects on colorectal

cancer risk. A detailed discussion of the extensive catalog of candidate genetic variants is beyond the scope of this chapter.

cancer risk. A detailed discussion of the extensive catalog of candidate genetic variants is beyond the scope of this chapter.

MODIFIABLE RISK FACTORS

Environmental lifestyle and dietary influences are considered to represent modifiable risk factors for colorectal cancer. Epidemiologic studies evaluating associations between the environment and colorectal cancer have shown that colorectal cancer incidence in populations migrating from low-risk to high-risk countries approaches that of the new host nation within a generation or two.17,18 For example, offspring of Japanese migrants to the United States have a similar colorectal cancer risk to white Americans that is three to four times that of Japanese people in Japan.18 Colorectal cancer risk is clearly related to a variety of environmental influences, including medications, exposure to cigarette smoke, physical activity, obesity, and alcohol use. Numerous dietary factors have been implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis, although the evidence is generally more inconsistent than that of lifestyle factors. Methods used to measure dietary influences vary widely and include diet records, diet histories and food frequency questionnaires, 24-hour dietary recall, and other forms of self-reporting. Thus, intake is often misreported or imprecise. Only widely studied dietary factors related to colorectal cancer, such as folate and other B vitamins, fiber from grains, fruits and vegetables, calcium and vitamin D, and red and processed meats, are discussed in this chapter.

Aspirin and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs

Epidemiologic, clinical, and observational studies have consistently shown that aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) protect against colorectal cancer and substantially reduce its incidence. Numerous epidemiologic studies have demonstrated decreased colorectal cancer incidence, prevention of adenoma recurrence, and reduction in colorectal cancer mortality among regular users of these agents.19,20 The effect of NSAIDs ranges from 20% to 60% reduced risk of colorectal cancer based on relative risk estimates of 0.4 to 0.8.19 Presumably, inhibition of the cyclooxygenase-2 pathway reduces prostaglandin synthesis and cell growth, although other biologic mechanisms of action unrelated to prostaglandin metabolism may also be important. These agents modulate insulin-mediated metabolism and reduce inflammation, both of which are important to colorectal carcinogenesis, as discussed in subsequent sections.21

Despite epidemiologic evidence supporting NSAID use in the prevention of colorectal cancer, the American Cancer Society and other groups have not yet endorsed their routine use in cancer prevention because of concerns regarding toxicity and bleeding risk. However, recent findings suggest that low-dose aspirin (75 mg/day) protects against colorectal cancer in the general population after only 5 years of use and may tip the scale in favor of future recommendations.22,23

Hormone Replacement Therapy

Most colorectal cancer patients are men, especially patients younger than 50 years of age, raising the possibility that hormonal influences play a role in the development of colorectal carcinoma. Estrogens decrease colonic transit time and production of insulin-like growth factor-1, thereby modifying potential cancer risk factors. Some colon cancers express estrogen receptor-β, which could modify the effect of hormone replacement therapy on tumor growth.24

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree