Major Concepts

Outbreaks

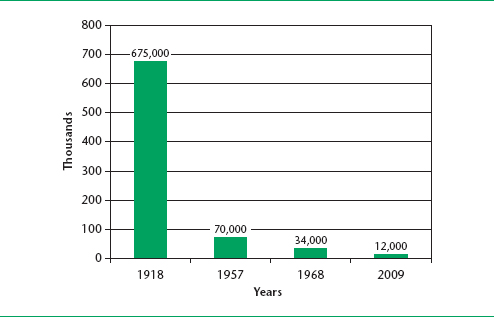

Influenza infections typically occur as sporadic cases, local outbreaks, and seasonal epidemics resulting from antigenic drift. Pandemics arise by antigenic shift and are rare but typically much more pathogenic. Four human influenza pandemics have occurred since 1900. Several regions of the world have recently experienced sporadic outbreaks of H5N1 avian influenza in humans. H5N1 infection is associated with a high mortality rate, especially in Southeast Asia. Almost all of the human infections resulted from contact with ill or dead birds or contaminated material from them. Due to differences between the cellular binding sites of human and avian influenza viruses, avian influenza viruses are very rarely able to be transmitted between humans. Beginning in 2009, a new strain of H1N1 virus spread rapidly throughout the world. This virus contained genetic information from influenza viruses of swine, birds, and humans and generated great concern that it would result in death rates similar to those experienced in the devastating 1918 pandemic. Fortunately, this did not occur, and the 2009–2010 H1N1 pandemic resulted in a fatality rate slightly lower than that of a typical year. The massive mobilization of health care resources and enormous associated expenses may nevertheless serve to alert the medical profession and the public to the necessary actions that must be taken when a true public health emergency does occur.

Symptoms

Influenza is usually self-limiting, with rapid and complete recovery from uncomplicated infections. Serious or fatal complications may occur in some populations, including secondary bacterial pneumonia, Reye syndrome, encephalitis, and myocarditis. Persons at high risk include the elderly, individuals with chronic health problems, and the immunosuppressed.

Prevention

Vaccinations are recommended for at-risk populations as well as young children, health care workers, residents of long-term care facilities, and pregnant women. Rapid mutation by influenza viruses allows them to escape immune responses against strains to which an individual was previously exposed via infection or vaccination. Annual immunization is therefore recommended to defend against newly arising viral variants. Other means of preventing infection include personal hygienic practices.

Infection

Influenza is caused by single-stranded RNA viruses of the Orthomyxoviridae family. They are divided into three general types: A, B, and C. A and B types are responsible for human epidemics and cause more severe disease symptoms than type C. Type A viruses also infect animals other than humans, including pigs and birds, and are solely responsible for pandemics. They are divided into subgroups based on differential expression of the hemagglutinin and neuraminidase surface glycoproteins.

Protection

Treatment for influenza often entails bed rest, aspirin, and supportive care. Several types of antiviral compounds may also be used. Adamantanes may have neurological side effects, and the avian H5N1 strains have developed resistance to them. Most H5N1 isolates retain susceptibility to neuraminidase inhibitors, and these drugs are becoming more widely available.

Influenza viruses infect the respiratory tract, causing the familiar symptoms of fever, cough, sore throat, muscle aches, and general malaise. While most individuals usually recover in a week or two, some 20,000 to 40,000 deaths occurred in each of 11 recent epidemics in the United States alone, making this illness a very important public health care concern. Infection rates are highest among school-aged children; however, the elderly and individuals with chronic health problems (including cardiac, pulmonary, renal, and metabolic diseases, and anemia) and immunosuppressed individuals are particularly susceptible to severe disease manifestations and death. The most dangerous forms of influenza outbreaks are the periodic influenza pandemics. In the not-so-distant past, these have occurred in 1889, 1918, 1957, and 1968. Since then, the H3N2 type (the same general type prevalent in 1968) has killed 400,000 Americans, 80% to 90% of whom were over the age of 65 years. H1N1 type (the general type prevalent in 1918) reappeared in 1976 and again in 2009, both times promoting fears of massive loss of life that, fortunately, did not materialize.

Sporadic cases of influenza, localized outbreaks, and epidemics occur frequently, and individuals with chronic illnesses or compromised immune systems are at greatest risk. Epidemics are most frequent in the winter months in temperate climates and in the rainy season in tropical regions. Pandemics recur infrequently, are more pathogenic, and often strike wider segments of the population. These require major antigenic changes in viral surface glycoproteins, the ability to sustain high levels of human-to-human transmission, and pathogenicity in humans. People residing in closed environments, such as nursing homes, mental health facilities, and boarding schools, generally have higher rates of infection. Ten pandemics are believed to have occurred in the past 300 years. Several of the most recent are discussed here.

1918 “Spanish Flu” Pandemic (Type H1N1)

The “Spanish flu” pandemic of 1918 caused the largest numbers of recorded deaths from an infectious disease in this short of a period of time. It is believed to have begun as a viral infection of pigs in the American Midwest. A mild form of this disease then occurred in humans in March 1918. The virus responsible is believed to have arisen as a result of a reassortment of genomic RNA from human and pig influenza viruses. This form of influenza struck troops gathered in an American army base in Kansas prior to transport to France for service in World War I. Due to the speed of transportation at the time and to the state of enhanced travel due to the worldwide military conflict, the infection was able to circle the globe within four months. By August of that year, major outbreaks were reported in France, Sierra Leone, and Boston.

The loss of life was massive and was most pronounced among young adults. Half of the soldiers who died during World War I died of influenza. In one Alaskan village, 85% of the population died within one week. Some South Pacific islands suffered mortality rates of 20%. More than 675,000 deaths occurred in the United States and 20 to 50 million more throughout the world.

1957 “Asian Flu” Pandemic (Type H2N2)

This pandemic originated in central China in 1956 or 1957, migrated to Hong Kong, and then spread to other areas of the world. It entered the United States in June 1957 with the arrival of naval personnel at Newport, Rhode Island, or San Diego, California. The first recognized outbreak in the country was during a conference of high school girls in Davis, California. From there, the flu was transported to another large conference of students from 43 states in Grinnell, Iowa. Attendees soon spread the epidemic throughout the country. An estimated 70,000 deaths occurred in the United States.

1968 “Hong Kong Flu” Pandemic (Type H3N2)

This pandemic originated in Hong Kong in early 1968 and reached the United States later that year. It was responsible for 34,000 deaths in the nation. Variants of the H3N2 subtype remain in circulation.

1976 “Swine Flu” (Type H1N1)

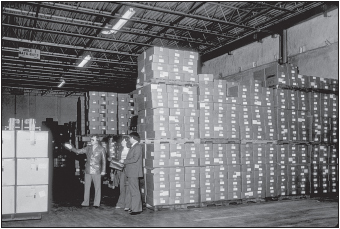

In 1974, a swine influenza virus was found in autopsied lung tissue of a young farmer after treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In February 1976, five cases of human infection with a swine influenza virus were found among army recruits at Fort Dix, New Jersey. It was apparently transmitted between humans, for about 500 other people in that part of the state were also infected. This particular influenza strain caused a great deal of concern because of its host species of origin and because it was of the H1N1 type responsible for the massive destruction in 1918. A national movement was initiated in the United States to immunize all Americans against this variant via the National Influenza Immunization Program. This program began in October 1976, and 40 million people were vaccinated before the program was halted in mid-December. The vaccine had proved to be dangerous, and by January 1977, more than 500 cases of Guillain-Barré syndrome had been reported, resulting in 25 vaccine-related deaths. This syndrome is a neurological disorder, potentially resulting from an immunopathological response to the vaccine. Its primary symptom is weakness, with potential for the involvement of respiratory muscles. Most affected individuals recover within three months. Fortunately, the feared pandemic did not occur, confirmed cases during this outbreak being confined to New Jersey.

FIGURE 19.2 Boxes of “swine flu” vaccine, stored in connection with the National Influenza Immunization Program

Source: CDC.

Influenza is typically characterized by fever of 102°F to 104°F and chills, sore throat, dryness of the nasopharyngeal area, cough that aggravates substernal pain, headache, retro-orbital pain, severe myalgia (muscle aches) that may particularly affect the back and limbs, fatigue, prostration, and general malaise. Gastrointestinal involvement, including nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, is present in up to 25% of infections of schoolchildren. Due to rapid antigenic changes in the virus (to be discussed shortly), individuals may be infected by slightly different influenza variants every year and hence develop disease repeatedly. In uncomplicated cases, infection is usually self-limiting and resolves completely within one week. In susceptible persons, serious complications may occur, including infection with bacteria, especially Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, or Streptococcus pyogenes, resulting in pneumonia. Encephalitis, with confusion, delirium, and coma, may occur, as well as myocarditis.

Much of the danger arising during influenza epidemics results from their rapidity, the prevalence of morbidity, and the severity of complications. Reye syndrome, a serious complication affecting the central nervous system and liver, may occur in children receiving aspirin or other salicylates. It is more common in those infected with type B influenza. During pandemics of type A influenza, the viral strains may be considerably more pathogenic. In 1918, infected persons’ lungs filled with blood and body fluids, potentially drowning the person within two to three days. Dark areas frequently occurred on the skin as well.

Viral Types

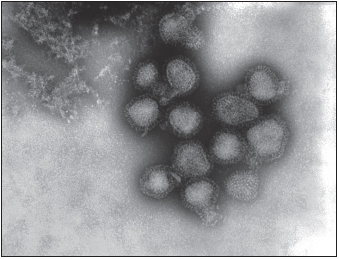

Influenza results from infection with influenza virus of the Orthomyxoviridae family, first isolated in 1933. The virus particles are spherical to ovoid, 80 to 120 nanometers in diameter, surrounded by a lipid bilayer outer membrane obtained from the host cell. Inside of the envelope, the inner matrix surrounds the nucleocapsid containing single-stranded, negative-sense genomic RNA and several proteins, including the RNA polymerase needed for replication. The genome consists of eight single-stranded RNAs encoding ten proteins.

Viruses may be divided into three major categories—A, B, and C—based on antigenic differences in viral nucleoproteins and matrix proteins. Types A and B cause winter epidemics; C viruses cause only mild illness. Type A influenza viruses cause disease in humans, pigs, birds, horses, mink, seals, and whales. They have been responsible for all of the recorded pandemics. Bird reservoirs are present for all known A subtypes. Type B viruses affect only humans. They cause some of the regional epidemics but not pandemics.

Type A viral subtypes are differentiated on the basis of two surface molecules, hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (N). As stated earlier, the Spanish flu, the Swine flu, and the 2009–2010 flu strains were of the H1N1 type. Several types of hemagglutinin have been reported in humans—H0, H1, H2, H3, H5, and H7; H5 and H7 are less common and were derived from avian viruses. Two types of neuraminidase commonly occur in humans—N1 and N2; infection with N7 is rare. Influenza variants are named according to their site of isolation, culture number, year of isolation, and, for A strains, the H and N type. Several such variants include A/Singapore/1/57 (H2N2), A/Hong Kong/1/68 (H3N2), A/New Jersey/8/76 (H1N1), and B/Yamanashi/166/98.

FIGURE 19.3 H3N2 “Hong Kong flu” virus showing spikes of hemagglutinin and neuraminidase on the surface

Source: CDC/Fred Murphy.

Life Cycle

Influenza viruses typically enter a host by inhalation, but infection may also occur by direct contact with infectious material, which may persist in this state for 48 hours, especially under conditions of low humidity or cold. The viruses primarily infect tracheobronchial epithelial cells of the upper respiratory tract and major airways but may also infect the lower respiratory tract. This process involves several glycoproteins on the viral surface. Trimers of the viral hemagglutinin bind to a sugar, sialic (N

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree