Marlene L. Durand

Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis refers to bacterial or fungal infection inside the eye involving the vitreous and/or aqueous humors. Most cases of endophthalmitis are caused by bacteria and present acutely. Acute endophthalmitis is a medical emergency because delayed or inadequate therapy may result in irreversible vision loss. Endophthalmitis may be either exogenous, in which organisms are introduced directly into the eye from an external source, or endogenous, in which the eye is seeded during bacteremia or fungemia. The majority of cases are exogenous and occur after eye surgery, intraocular injections (e.g., given for treatment of macular degeneration), and eye trauma, from extension of corneal infection (keratitis), or through a glaucoma filtering bleb. In exogenous endophthalmitis, the infection is confined to the eye and there are rarely any systemic symptoms. In endogenous endophthalmitis, patients may have prominent symptoms of the underlying systemic infection (e.g., endocarditis).

Categories

It is useful to further classify endophthalmitis into several categories (Table 116-1). The presentation and typical pathogens vary by category, but treatment almost always requires the intraocular injection of antibiotics and, often, vitrectomy.

TABLE 116-1

Endophthalmitis Categories and the Most Common Pathogens in Each

| CATEGORY | PATHOGEN |

| Acute postcataract | Coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| Chronic postcataract | Propionibacterium acnes |

| Postinjection | Viridans streptococci, coagulase-negative staphylococci |

| Bleb-related | Streptococci, Haemophilus influenzae |

| Post-traumatic | Bacillus cereus |

| Endogenous | Staphylococcus aureus, streptococci, gram-negative bacilli |

| Fungal | Candida, Aspergillus, Fusarium |

Acute Postcataract Endophthalmitis

Cataract surgery is one of the most common surgeries performed worldwide, with over 2 million cataract surgeries performed annually in the United States alone. Removing a cataract, or opacified lens, requires making an incision through the sclera or cornea and then through the anterior lens capsule to remove the lens. An attempt is made to leave the posterior lens capsule intact. In most cases, an artificial intraocular lens (IOL) is placed in the residual capsular bag. The incidence of postcataract endophthalmitis is 0.1% to 0.2% in several large series worldwide.1,2,3,4 The pathogenesis of postcataract endophthalmitis has been well established, and in nearly all cases the source of the bacteria is the patient’s own eyelid or conjunctival flora.5,6 These bacteria contaminate the aqueous at the time of surgery, and many studies have found that aqueous samples taken at the close of surgery often grow bacteria (8% to 43% of cases).7–10 Endophthalmitis is rare despite this high rate of intraoperative contamination, and rabbit experiments with Staphylococcus epidermidis suggest that the immune system can clear small inocula of bacteria of low virulence from the aqueous.11

An incision through the cornea rather than the sclera is commonly used for cataract surgery, but this may slightly increase the risk for endophthalmitis.12,13 These clear cornea incisions are considered self-sealing and do not require sutures, but such incisions may gape intermittently in the early postoperative period, leading to potential contamination.14,15

The vitreous is more susceptible to infection than the aqueous, and the risk for postcataract endophthalmitis is nearly 14 times higher if the posterior lens capsule is inadvertently broken during surgery, thereby establishing a communication with the vitreous.16 Silicone rather than acrylic IOLs also increase the risk for endophthalmitis.4

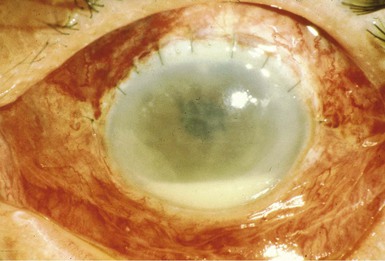

Symptoms of endophthalmitis occur within 1 week of surgery in 75% of patients and include eye pain (74%), redness (82%), and decreased vision (94%).17 The patient often has no symptoms for several days and then symptoms develop rapidly within 24 hours. The pain is often not severe, and patients feel otherwise well. Signs of systemic illness are absent: there is no fever, and the white blood cell count is normal in two thirds of patients and only mildly elevated in the rest. The physical examination is unremarkable except for the involved eye, which is usually injected and has a hypopyon (Fig. 116-1). The hypopyon is a layer of white blood cells in the anterior chamber. Slit-lamp examination reveals white blood cells in the aqueous and vitreous. Inflammation may be so severe that it obscures the funduscopic view of the retina.

In temperate climates, nearly all postcataract endophthalmitis cases are due to bacteria and 95% are due to gram-positive cocci. Coagulase-negative staphylococci are the major pathogens, causing 70% of culture-positive cases, regardless of whether a scleral tunnel or clear cornea incision was used for the surgery.17,18 Staphylococcus aureus (10%), streptococci (9%), other gram-positive cocci (5%), and gram-negative bacilli (6%) account for the remaining cases. Streptococci (e.g. viridans streptococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and β-hemolytic streptococci) are associated with a particularly poor outcome. Thirty percent of patients with clinical evidence of endophthalmitis have negative or equivocal vitreous cultures.17 In tropical countries such as India, fungi typically cause 10% to 15% of postoperative endophthalmitis cases.19

Chronic Postcataract Endophthalmitis

Chronic postcataract endophthalmitis, also termed chronic pseudophakic endophthalmitis in reference to the IOL, is a rare, indolent infection that is almost always due to Propionibacterium acnes. A few cases have been caused by coagulase-negative staphylococci and diphtheroids. Patients present with a persistent decrease in vision in the involved eye, and half also have eye pain, which is usually mild. On slit-lamp examination there are white blood cells in the anterior chamber and usually also in the anterior vitreous. A small hypopyon is present in half of patients, and in nearly all patients there is a white plaque in the residual posterior lens capsule. Patients often are misdiagnosed as having anterior uveitis and may be treated for months with topical corticosteroids, producing a waxing and waning course of intraocular inflammation. Diagnosis may be difficult because aqueous or vitreous cultures are frequently negative, even in cases in which electron microscopy of the removed artificial lens or lens capsule shows bacteria.20,21 Biopsy of the posterior lens capsule, including the white plaque, is most likely to yield positive cultures, and capsulectomy is important for successful treatment.22 Leaving the original IOL in place has a 40% to 50% relapse rate.

Postinjection Endophthalmitis

Neovascular, or “wet,” macular degeneration accounts for approximately 10% of macular degeneration cases. In recent years, wet macular degeneration has been treated with intravitreal injections of anti–vascular endothelial growth factors, such as bevacizumab, ranibizumab, or pegaptanib. These injections are usually repeated monthly, over for many months. Each injection carries a small risk for endophthalmitis. A study using a Medicare database of nearly 41,000 injections found an endophthalmitis rate of 0.09% per injection.23 This is similar to the postcataract endophthalmitis rate of 0.1%, but the patient faces this risk with each monthly injection. Symptoms usually develop within 1 week after injection and include eye pain and decreased vision. A hypopyon is found in about 80% of patients. As with postcataract endophthalmitis, gram-positive cocci cause 95% of cases but viridans streptococci cause a much higher percentage of postinjection cases (25%) than postcataract endophthalmitis cases (9%). Patients with streptococcal endophthalmitis have a poor visual prognosis.

Bleb-Related Endophthalmitis

A filtering bleb is a defect in the sclera, covered only by conjunctiva, that is surgically created to control glaucoma refractory to medical treatment. The bleb allows excess aqueous to filter out of the eye and into the systemic circulation. Because the only barrier to the aqueous humor at the site of the bleb is the thin conjunctiva, acute endophthalmitis may occur at any time, particularly if the eye becomes colonized by virulent bacteria. Bleb-related endophthalmitis usually occurs abruptly, months to years after bleb surgery. One study found that endophthalmitis developed an average of 2 years after bleb placement (range, 1 month to 8 years).24 The incidence of endophthalmitis in another series was 1.3% per patient-year.25 Bleb-related endophthalmitis is typically fulminant. Patients complain of sudden onset of eye pain and decreased vision. On examination, the patient has an injected eye, a hypopyon, and often a purulent bleb.

Streptococci, including S. pneumoniae and viridans streptococci, and coagulase-negative staphylococci are the predominant pathogens in recent series, each causing 20% to 30% of cases.24,25,26,27 Other causes include S. aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis, and, in one series,27 enterococci and Serratia.

Post-traumatic Endophthalmitis

Post-traumatic endophthalmitis develops in 3% to 10% of eyes that have sustained penetrating trauma.28,29 Endophthalmitis is most likely to follow a lacerating injury with a metal object, whereas glass laceration injuries and blunt trauma rarely lead to endophthalmitis. Lens disruption is another major risk factor and was present in 86% of post-traumatic endophthalmitis cases in one study.30 Other risk factors include retained intraocular foreign bodies and delay in primary closure of greater than 24 hours.31,32 Bacillus species (often Bacillus cereus) and coagulase-negative staphylococci are the major causes of post-traumatic endophthalmitis. Whereas eyes with endophthalmitis due to coagulase-negative staphylococci often have a good visual outcome, those with Bacillus endophthalmitis usually lose all useful vision.33 Rare cases of successful therapy have been described.34 Onset of symptoms in 12 to 24 hours after trauma, marked intraocular inflammation, and a ring corneal infiltrate are characteristic of this infection. Other causes of post-traumatic endophthalmitis include streptococci, gram-negative bacilli such as Klebsiella and Pseudomonas, and molds.35,36 Unlike bacterial cases, post-traumatic endophthalmitis due to molds usually has a subacute presentation (see later discussion).

Prompt repair of open globe injuries is important in preventing endophthalmitis, and prophylactic antibiotics may also lower the risk. One prospective trial that gave prophylactic intravenous antibiotics for 5 days reported a low overall post-traumatic endophthalmitis rate of 2.6% and found that intravitreal antibiotics given at the time of surgical repair significantly lowered the rate in those eyes with intraocular foreign bodies.28 A retrospective study of 558 patients who underwent surgical repair of open globe injuries and received 2 days of prophylactic intravenous vancomycin plus ceftazidime beginning on presentation reported one of the lowest rates of post-traumatic endophthalmitis in the literature at 0.9%.37

Endogenous Bacterial Endophthalmitis

Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis results from bacteremic seeding of the eye. Usually a significant focus of bacteremia is identified, such as endocarditis or an intraabdominal abscess, but transient bacteremia rarely may cause endophthalmitis. Endocarditis was the source in nearly 40% of cases in one U.S. series of 28 patients, whereas 1 patient developed endophthalmitis 2 days after upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, presumably from transient bacteremia.38 Patients who are injection drug users also are at risk for endophthalmitis from transient bacteremia. Gastrointestinal or hepatic abscesses, urinary tract infections, meningitis, and infected indwelling catheters are other sources of bacteremia in endogenous endophthalmitis case series.38,39,40 In Taiwan, Singapore, and other east Asian nations, pyogenic liver abscess due to Klebsiella pneumoniae is prevalent41 and may be complicated by endogenous endophthalmitis in almost 10% of patients.42

The bacteria involved in endogenous endophthalmitis (e.g., S. aureus, streptococci, gram-negative bacilli) typically cause acute inflammation, and most patients present with acute decrease in vision and eye pain. These may be their only complaints, and the source of bacteremia may not be apparent initially. In one series, half of the patients presented to an ophthalmologist.38 In a series of 27 patients with fungal or bacterial endogenous endophthalmitis, fewer than 20% of patients had fever on presentation and more than 40% had an unremarkable general physical examination.40 A delay in diagnosis is common, but endophthalmitis should be considered in any patient who presents with acute vitritis and hypopyon. Patients with known endocarditis should be monitored for new visual complaints and examined by an ophthalmologist promptly if these develop.

Diagnosis usually is established by culture of vitreous samples or by blood cultures in patients with endophthalmitis whose vitreous cultures fail to grow. Blood cultures are positive in approximately three fourths of patients tested, as are vitreous cultures.38 In North America and Europe, streptococci (S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus anginosus group, and group A and group B streptococci) cause 30% to 50% of cases and S. aureus causes about 25% of cases; gram-negative bacilli (e.g., Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, Serratia) cause only one third of cases.38,40 In Asia, gram-negative bacilli (e.g., Klebsiella, E. coli) cause the majority of cases,39,43 with K. pneumoniae accounting for 60% of cases in one study.43 In Taiwan, a syndrome of Klebsiella liver abscess and endophthalmitis occurring primarily in diabetic patients has been well-described44 and appears to be associated with a strain of K. pneumoniae exhibiting a hypermucoviscosity phenotype.45

Fungal Endophthalmitis

Fungal endophthalmitis cases may be divided into two major categories by incidence and response to therapy: Candida endophthalmitis and mold endophthalmitis. In industrialized nations and colder climates, Candida endophthalmitis is more common than mold endophthalmitis, whereas the reverse is true in tropical countries. Candida endophthalmitis is most often endogenous and usually responds well to treatment, whereas mold endophthalmitis is almost always exogenous and successful therapy is uncommon. Endophthalmitis due to Cryptococcus or the dimorphic fungi, Histoplasma and Coccidioides, is rare and almost always a result of disseminated disease.46–48

Endogenous Candida Endophthalmitis

In the literature on endogenous Candida endophthalmitis, the term is used variably. In some reports, it is used to describe both chorioretinitis and “endophthalmitis” (i.e., infection with significant vitritis), whereas in other reports it is used only for those cases with significant vitritis (the usual meaning of endophthalmitis). A better term is ocular candidiasis, which encompasses the spectrum of intraocular infection from chorioretinitis to endophthalmitis. To avoid confusion, we will reserve “endophthalmitis” for those cases with significant vitritis and the degree of vitritis will be described. Ophthalmologists grade the degree of vitreous inflammation on a scale of 1 to 4, with 1+ white blood cells considered mild vitritis, and 4+ cells severe vitritis. Determining the degree of vitreous inflammation is important. Ocular candidiasis with moderate to severe vitritis (i.e., endophthalmitis) requires intravitreal injection of amphotericin or voriconazole and usually vitrectomy, in addition to systemic therapy. In contrast, chorioretinitis with minimal or no vitritis usually resolves with systemic therapy alone. Visual outcome also depends on the initial degree of vitreous involvement.49

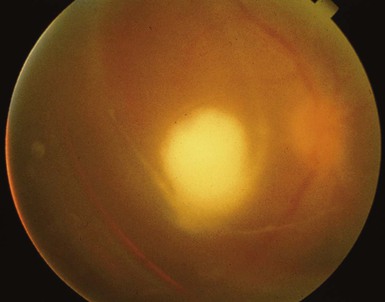

Candidemic seeding of the eye starts in the highly vascular choroid, so chorioretinitis is the initial manifestation seen in most prospective trials of candidemia. In chorioretinitis, there are typically several white chorioretinal lesions but a clear vitreous. As infection progresses, there is significant vitritis, and examination reveals a cloudy vitreous that often contains inflammatory “fluff balls” (Fig. 116-2). Chorioretinitis is much more common than endophthalmitis, and chorioretinitis often is asymptomatic. In a prospective multicenter study of 118 hospitalized patients with candidemia, 9% were found to have chorioretinitis, almost none had eye symptoms, and none had endophthalmitis (significant vitritis).50 In another trial of 370 patients with candidemia, 16% had possible or probable ocular involvement, although only 1.6% had endophthalmitis.51 Undiagnosed and untreated chorioretinitis may progress to endophthalmitis, and patients with the latter usually present with a gradual and painless decrease in vision. This presentation is common in outpatients who have had transient, usually asymptomatic, candidemia. The major risk factors for candidemia in outpatients are indwelling central venous catheters (or recent history of such a catheter) and illicit injection drug use. The latter is the most common risk factor in some recent studies and accounted for 70% of cases of fungal endophthalmitis between 2001 and 2007 in a study from Australia.52 Outpatients who present with endogenous Candida endophthalmitis often have a subacute presentation (i.e., 2 weeks of progressive vision loss) and may be misdiagnosed as having uveitis, especially if a history of an indwelling central venous catheter in the previous months, or injection drug use, is not elicited. Such patients do not usually show other signs of systemic infection, and blood cultures are usually negative, because candidemia was transient and occurred days or weeks earlier. There is often a substantial delay in diagnosis, and such a delay may lead to permanent vision loss. This delay was illustrated by a retrospective 10-year study, published in 1997, of 15 patients with endogenous Candida endophthalmitis (11 from indwelling lines): the average time from onset of symptoms to treatment of endophthalmitis was 2 months.53 Although vitreous aspirate alone may yield the diagnosis in some cases, this is often nondiagnostic and a vitrectomy for culture is usually necessary to make the diagnosis.

Exogenous Candida Endophthalmitis

Exogenous cases are uncommon but may develop after eye surgery, eye trauma, or keratitis.54 Initially, only the aqueous may have inflammation, and then the infection may extend into the vitreous. Candida parapsilosis has been a common cause of postsurgical outbreaks of Candida endophthalmitis, possibly because this species appears to survive well in irrigation fluids and on prosthetic materials.55 Rarely, endophthalmitis may develop after corneal transplantation (postkeratoplasty endophthalmitis). The overall incidence of bacterial and fungal postkeratoplasty endophthalmitis is 0.2% in the United States.56,57 Contaminated donor corneas are usually the source, and culture of the unused donor corneal rim at time of surgery may be helpful. A rim culture that grows Candida species predicts a 3% chance of developing Candida endophthalmitis.56 Awareness of this increased risk may allow for earlier detection and treatment of postkeratoplasty fungal endophthalmitis. Contamination of donor corneas with Candida may develop during storage in standard media that contain broad-spectrum antibacterial antibiotics but typically no antifungal agents.57

Mold Endophthalmitis

Endophthalmitis due to molds is rare in Western countries. In the United States, it is most common in tropical areas, such as Florida, where 6% of 278 endophthalmitis cases treated between 1996 and 2001 were due to Aspergillus and other molds.58 In tropical countries, such as India, fungal endophthalmitis is a significant problem. Molds accounted for 22% of 124 postcataract endophthalmitis cases in northern India59 and 21% of 170 postoperative endophthalmitis cases in southern India.60

Mold endophthalmitis is usually exogenous, with most cases occurring after eye surgery, after penetrating eye trauma, or as an extension of fungal keratitis (keratomycosis).54

Postoperative mold endophthalmitis usually presents within days to weeks of eye surgery. Patients complain of eye pain and decreased vision. The surgical corneal or scleral incision may appear normal or may show evidence of wound involvement.61 Extensive eye involvement (cornea, anterior segment, vitreous) and early presentation (37% within 1 week) characterized postcataract fungal endophthalmitis in one series from India.62 Post-traumatic mold endophthalmitis also may present relatively quickly; in a series from India, the average time to presentation after eye trauma was 7 days.63 In endophthalmitis due to keratomycosis, the diagnosis is made when there is evidence of extension of the corneal infection into the aqueous. On slit-lamp examination, the fungal keratitis extends through the full thickness of the cornea and there is significant inflammation in the aqueous. Sometimes, frondlike projections may be seen extending from the back of the cornea into the aqueous. Both corneal trauma and contact lens wear are risk factors for keratomycosis-associated endophthalmitis.

Endogenous mold endophthalmitis has been reported primarily in intravenous drug abusers or immunocompromised patients. The latter include organ transplant patients and patients with hematologic malignancies.64,65 Most of these immunocompromised patients have a focus of fungal infection elsewhere, usually the lungs.64,65

Aspergillus is the most common cause of mold endophthalmitis, causing 50% to 90% of cases.60,63 Fusarium is another common cause of mold endophthalmitis, and most cases result from Fusarium keratitis. Several recent cases occurred after a nationwide outbreak of Fusarium keratitis, from 2004 to 2006, associated with a contact lens cleaning solution.66,67 In this outbreak, 6% of cases developed endophthalmitis.66,68

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree