ENDOCRINE AND METABOLIC CONSEQUENCES OF OBESITY

Part of “CHAPTER 126 – OBESITY“

Various alterations in endocrine and metabolic function can be observed in obese individuals, including disturbances of growth hormone, changes of thyroid function, adrenal hormone metabolism, and insulin secretion and insulin action and alterations in lipid metabolism that may lead to hyperlipidemia. These are thought to be secondary to, rather than a primary characteristic of, obesity.

OBESITY AND GROWTH HORMONE

Growth hormone secretion in response to hypoglycemia or arginine is decreased in obese compared with lean patients, but weight reduction restores normal responses and plasma levels.

OBESITY AND THYROID FUNCTION

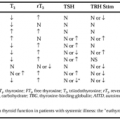

Thyroid function is normal in most obese patients, but subtle changes in thyroid hormone metabolism may occur. Plasma triiodothyronine (T3) levels are increased and reverse triiodothyronine levels (rT3) are decreased in many obese patients, whereas plasma thyroxine (T4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels are normal (see Chap. 33). The plasma T3 and rT3 changes are reversed by weight loss and T3 may even become subnormal although thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) remains normal. Hypothyroidism is rarely a cause of obesity, but it should be considered in the differential diagnosis. The obesity caused by hypothyroidism usually is mild, and restoration of euthyroidism eliminates the problem.

OBESITY AND ADRENAL FUNCTION

Cortisol secretion rates are increased in obesity, but normal plasma cortisol concentration, normal diurnal variation in secretion, and normal response to dexamethasone suppression distinguish obesity-associated alterations in adrenal function from Cushing syndrome (see Chap. 75). Total 24-hour urinary 17-hydroxycorticosteroids generally are increased in obese patients but are normal when expressed per kilogram of body weight. Twenty-four–hour urinary 17-ketosteroids may be normal or slightly increased in obesity. Weight reduction normalizes the cortisol secretion rate and 24-hour urinary 17-hydroxysteroid and 17-ketosteroid levels, indicating that these changes are secondary to obesity. However, hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing syndrome) can cause obesity; thus, it always should be considered and ruled out in an obese person (see Chap. 74). When Cushing syndrome is the cause of obesity, it tends to be mild and completely reversible after definitive treatment.

OBESITY AND SEX HORMONES

The onset of menarche is earlier in obese than in nonobese girls, and obese women often suffer from a variety of menstrual cycle abnormalities, including hypermenorrhea, oligomenorrhea, amenorrhea, irregular or anovulatory cycles, infertility, and premature menopause. Obesity is often associated with polycystic ovarian disease, hyperandrogenism, and hirsutism (see Chap. 96 and Chap. 101). Although the mechanism of these disorders in obese women is unknown, the disorders could be secondary to alterations in hypothalamic-pituitary function, to abnormalities in the synthesis or secretion of estrogens or androgens from the ovaries or adrenals, or to alterations in the metabolism of sex steroids by non–steroid-producing peripheral tissues. Elevation of plasma luteinizing hormone, reduction of plasma follicle-stimulating hormone, and increased luteinizing hormone/follicle-stimulating hormone ratios have been reported in some obese women. Elevated circulating levels of estrogens and androgens also have been reported in some obese women. These hormones may be of either ovarian or adrenal origin. Alterations in sex steroid metabolism, specifically increased conversion of androstenedione of adrenal origin to estrone and its metabolites by non–steroid-producing peripheral tissues, also may play a role in some of the menstrual cycle abnormalities and in the increase in prevalence of breast cancer in obese women.22 Conversely, an increased conversion of estrogen to androgen, which has been postulated to occur, may be a factor in creating hirsutism or abnormal menstruation. Most of these changes are reversible by weight loss.

In men with severe obesity, both serum total and free testosterone levels may be mildly decreased. Increased conversion of androgens to estrogens may result in increased serum estrogen levels. Usually, libido and potency remain normal.

Amenorrhea of hypothalamic origin, such as is found in starvation, occurs frequently in obese women who lose a great deal of weight. This is often accompanied by low T3 levels, leukopenia, and cold sensitivity. This may persist for long periods of time after weight loss and cannot be safely repaired by hormone therapy.

OBESITY AND DIABETES MELLITUS

Obesity is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes. On average, >70% of type 2 diabetics studied in various populations throughout the world are obese, with prevalence variation dependent upon the population studied.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree