Introduction

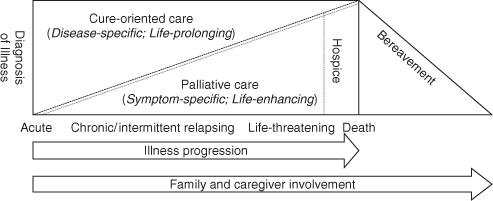

Palliative care (also known as supportive care) encompasses the assessment and treatment of pain and other non-pain symptoms with the goal of relieving suffering across multiple domains. Palliative care can be provided in conjunction with curative treatment at any point in a disease trajectory, even from the time of diagnosis (see Figure 135.1).

Figure 135.1 Palliative care is most effective for patients and their families when it is integrated across the healthcare continuum. It is optimally initiated in collaboration during the cure-oriented phase, continuing through the course of illness and culminating in end-of-life care (hospice), then bereavement support for family and caregivers. As the disease progresses, more palliative services are integrated into the patient’s care as needed. Simultaneously, the emphasis on curative (or life-prolonging) therapies diminishes as the goals of care focus more on palliative care measures (quality-of-life-enhancing).

Palliative care assists increasing numbers of people with chronic, debilitating and life-limiting illnesses. A growing number of programmes provide this care in a variety of settings: hospitals, outpatient settings, community programmes within home health organizations and hospices. Within these settings, dedicated teams may include physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, counsellors, nursing assistants, rehabilitation specialists, speech and language pathologists and other healthcare professionals. These providers assess and treat pain along with other non-pain symptoms and also facilitate patient-centred communication and decision-making. The ideal palliative care delivery system fosters the coordination of continuity of care across settings throughout the disease continuum (see Figure 135.1). Whereas palliative care refers to an approach to care focused on symptom management and improving quality of life, palliative medicine refers to the medical specialty focused on providing palliative care. Despite the emergence of palliative medicine as a formally recognized medical specialty across the world, all physicians who care for patients with serious and advanced illnesses need to be able to provide appropriate pain and symptom management and identify and treat other sources of suffering in their patients. In order to achieve this goal, all physicians need training in palliative care.1–3

Palliative care services and palliative care domains are summarized in Tables 135.1 and 135.2, respectivly.

Table 135.1 Palliative care services.

|

Source: information from WHO’s Definition of Palliative Care, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/(last accessed 26 November 2011).

Table 135.2 Palliative care domains.

| Area | Examples |

| Physical | Pain, shortness of breath, nausea, fatigue, weakness, anorexia, insomnia, confusion, constipation, treatment side effects, functional capacities, treatment efficacy and alternatives (and patient and family preferences) |

| Psychological/psychiatric | Anxiety, depression, care-giving needs or capacity of family; stress; grief and bereavement risks for the patient and family (e.g. depression and co-morbid complications); coping strategies |

| Social | Family structure and geographic location; cultural concerns and needs; finances; sexuality; living arrangements; caregiver availability; access to transportation; access to prescription and over-the-counter medicines |

| Spiritual/religious/existential | Spiritual background, beliefs and practices of the patient and family; hopes and fears; life completion tasks; wishes regarding care setting for death |

Source: information from National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, 2nd edn, 2009, http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org (last accessed 7 November 2011).

Palliative and Hospice Care

Palliative care is not synonymous with hospice care in that hospice utilization in the USA requires that a physician endorse a prognosis of 6 months or less in order for a patient to qualify for services. Enrolment in a hospice programme is but a final piece in what the whole of palliative care provides, ideally from the onset of serious life-threatening illness. The goal of palliative care is to prevent and relieve suffering and to support the best possible quality of life for patients and their families, regardless of the stage of the disease or the need for other therapies. Palliative care is both a philosophy of care and an organized, highly structured system for delivering care. The fundamental elements of hospice and palliative care maintain the following:4

Symptom Assessment and Treatment

Palliative care aims at the relief of suffering caused by physical, psychosocial and spiritual aspects of disease and utilizes an interdisciplinary team to provide care. By focused symptom management and clear goals of care, patients living with advanced illness can improve quality of life and spend valuable time with friends, family and loved ones. One of the core principles of the delivery of end-of-life care is the alleviation of pain and other physical and psychological symptoms. The goal of pain and symptom management is a reduction of the symptoms to a level that the patient defines as satisfactory. Providers should be careful not to state that all symptoms will be completely alleviated, because although this goal is sometimes achievable, more often symptoms, such as pain and nausea, are attenuated to an acceptable level.

Pain

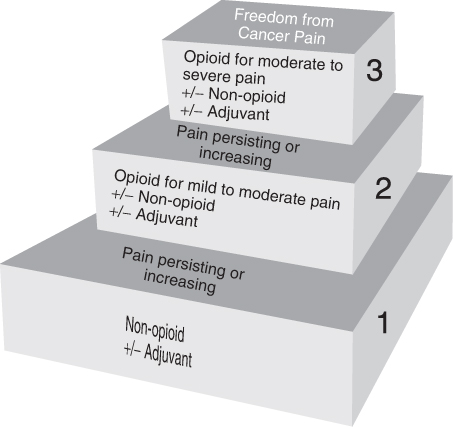

The optimal control of pain in the palliative care patient relies on the understanding of the underlying pathophysiology and mechanisms involved and include somatic, neuropathic and visceral aetiologies. These might include tumour invasion of local tissues or metastatic bone pain (somatic), nerve compression or chemotherapy-related nerve pain (neuropathy) or bowel obstruction (visceral). Therefore, management starts with the evaluation of the causes of the pain by a comprehensive history, physical and directed imaging as indicated by the initial evaluation.5 Many cases of advanced life-threatening illness require the use of opioids; providers should prescribe opioids in doses sufficient to relieve pain and to acquire skills in the management of predictable opioid side effects. Providers must also anticipate and correct patients’ misconceptions about the use of opioids, including side effects, addiction, somnolence and hastening of death. Because patients may become unable to take medications orally, the sublingual, transdermal, rectal and subcutaneous routes may be used. The World Health Organization (WHO) pain relief ladder (see Figure 135.2) is a well-established and reasonable starting point in the management of pain symptoms. If pain occurs, the first step is oral administration of medication in the following order: non-opioids (aspirin and paracetamol); then, as necessary, mild opioids (codeine); then strong opioids such as morphine, until the patient’s pain is attenuated. It should be noted that this approach has potential limitations in the context of longer survival and increasing disease complexity if used in isolation and without a comprehensive clinical approach to the pain syndrome. To complement this, combination and adjuvant therapies, including procedural interventions, are used where appropriate, tailored to the needs of an individual with the goals of optimizing pain relief and minimizing adverse effects.6, 7 Furthermore, older and debilitated patients’ ability to request ‘on demand’ (or PRN) medications should compel the provider to consider scheduled dosing, particularly if in a setting such as a long-term care facility where frequent and timely reassessment of pain can be limited by staffing. To maintain freedom from pain, drugs should be given ‘by the clock’, that is, every 2–6 h, rather than ‘on demand’. This three-step approach of administering the right drug in the right dose at the right time is inexpensive and 80–90% effective.8 Surgical intervention on appropriate nerves may provide further pain relief if drugs are not wholly effective (see Figure 135.2).

Figure 135.2 WHO’s Pain Ladder.8 Reproduced with permission from the World Health Organization from http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/index.html (last accessed 26 September 2011).

In essence, the optimal means of providing palliation of pain symptoms is first to consider evaluation and treatment of the underlying removal or minimization of the cause (i.e. disease-directed therapies). For example, in malignant bone pain, surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and/or bisphosphonates may be used.9 In infection, antimicrobials or surgical drainage of an abscess may be required. Alongside disease-directed therapy, there are a host of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies, which should be used on an individual basis depending on the clinical situation.

Non-Pain Symptoms

Dyspnoea and Respiratory Symptoms

Changes in respiratory patterns are common in dying patients. Breathing usually becomes shallow as death nears and periods of apnoea are common. Opioids are the main therapy for treating dyspnoea. Some patients and providers may not be familiar with using opioids for this purpose and should be educated. Secretions that accumulate in the pharynx due to the patient being too weak or unresponsive to swallow or cough can produce a rattling sound that can be distressing to the family. Deep suctioning should be avoided as it can lead to gagging and may be uncomfortable. Atropine, scopolamine or glycopyrrolate (the last does not cross the blood–brain barrier, thereby minimizing contribution to delirium) can be effective in reducing rattle by decreasing the amount of mucus and saliva produced. Rooms should be cool and well ventilated and a fan can aid in reducing the sensation of dyspnoea. It may be appropriate to stop taking blood pressure and monitor only respiratory rate and pulse in order to avoid disturbing the patient or causing alarm to the patient’s loved ones.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms: Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms in patients with advanced illnesses, including cancer, congestive heart failure, end-stage renal disease and AIDS. For patients and families facing a life-threatening illness, nausea and vomiting can cause substantial distress due to concerns about maintaining adequate nutrition and also fear that these symptoms indicate disease progression.10 Nausea and vomiting can be triggered by activation of any of four general pathways (Table 135.3).11

Table 135.3 General pathways that can trigger nausea and vomiting.

| Area | Activated by | Mediated by |

| Cortex | Meningeal irritation Increased intracranial pressure Cognitive/emotional factors | Anxiety |

| Chemoreceptor trigger zone (located in the floor of the fourth ventricle and lacks a blood–brain barrier) | Metabolic abnormalities Toxins Medications | Primarily by the dopamine (D2) receptor, but others include neurokinin-1 (NK1) and serotonin (5HT3) |

| Vestibular system | Motion or inner ear disease | Via histamine (H1) and muscarinic acetylcholine (ACh) receptors |

| Peripheral pathways. Signals transmitted along afferent tracts (vagus, glossopharyngeal, splanchnic and sympathetic nerves) |