CHAPTER 28 Echinococcosis

Etiology

Hydatid disease (echinococcosis) is the infection of humans by the larval stages of taeniid cestodes of the genus Echinococcus. Four species of Echinococcus are currently recognized, of which three cause distinct forms of disease: E. granulosus (cystic hydatid disease), E. multilocularis (alveolar hydatid disease), and E. vogeli (polycystic hydatid disease). The fourth species, E. oligarthrus, has only rarely (fewer than five cases) been identified as a cause of human disease. Diverse subpopulations of E. granulosus, distinguished by morphologic and biologic characteristics, have long been recognized; the taxonomic significance of these differences remains unresolved and controversial. However, recent demonstrations of consistent genetic differences has prompted calls for splitting this species.1 As a cause of morbidity in humans, Echinococcus species rank high among the helminths.

Life cycle

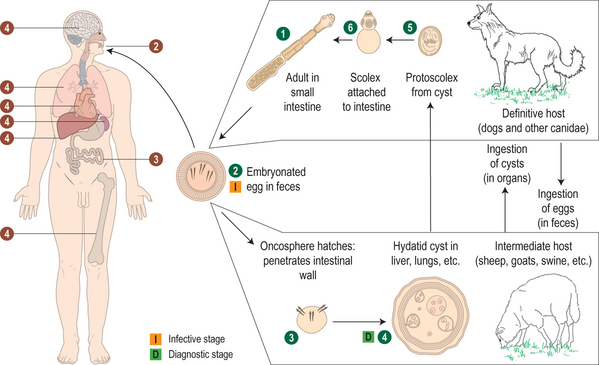

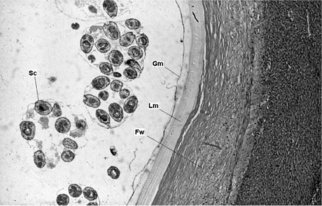

The life cycles of Echinococcus species involve carnivores as final hosts and herbivores or omnivores as intermediate hosts (Fig. 28.1). In their adult stage, these cestodes are small, ranging about 2–12 mm in length, with three to six segments. They typically localize in the lower duodenum and jejunum of the final host. Embryophores containing infective embryos are expelled in large numbers in the feces of the final carnivorous host. After ingestion by the intermediate host, the embryo is released into the small intestine, which it penetrates, and enters the portal circulation. The site of localization and development of the embryo to the larval or hydatid stage differs with species of Echinococcus and may be influenced as well by species of the intermediate host. Humans are an incidental intermediate host, since further development of these cestodes depends on ingestion of their larvae (hydatids) by a carnivore. The microscopic structure of a hydatid cyst is shown in Figure 28.2.

Epidemiology

Distribution and transmission patterns

Cystic hydatid disease (CHD) is caused by the larval stage of E. granulosus. Molecular studies using mitochondrial DNA sequences have identified nine distinct genetic types (G1–9) within E. granulosus.2,3 These include two sheep strains (G1, G2), two bovid strains (G3, G5), a horse strain (G4), the camelid strain (G6), a pig strain (G7), and the cervid strain (G8). A ninth genotype (G9) has been described in swine in Poland.2 The sheep strain (G1) is the most cosmopolitan form that is most commonly associated with human infections. The other strains appear to be genetically distinct, suggesting that the taxon E. granulosus is paraphyletic and may require taxonomic revision.2,3 The ‘cervid,’ or northern sylvatic genotype (G8), is maintained in cycles involving wolves and dogs and moose and reindeer in northern North America and Eurasia. Human infection with this strain is characterized by predominantly pulmonary localization, slower and more benign growth, and less frequent occurrence of clinical complications than reported for other forms.2 The presence of distinct strains of E. granulosus has important implications for public health. The shortened maturation time of the adult form of the parasite in the intestine of dogs suggests that, where echinococcidal drugs are used for controls, the period for administering antiparasite drugs to dogs will have to be shortened in those areas where the G2, G5, and G6 strains occur.4

E. granulosus is prevalent in broad regions of Eurasia, in several South American countries, and in Africa (Fig. 28.3). Humans become infected through association with dogs that have been fed viscera from slaughtered animals or have had access to carcasses or discarded offal of domestic ungulates in which the larvae are present.

Most cases of cystic echinococcosis reported in North America continue to be diagnosed in immigrants who acquired their infections in their countries of origin;5 historically, this was mainly Icelanders, Italians, and Greeks, but in more recent years increasing numbers of cases are diagnosed in persons of Middle Eastern and Asian origin [Schantz, unpublished].

E. granulosus is highly endemic in Argentina, southern Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay. In endemic areas the prevalence of infection in humans can be as high as 3–6%; 89% of adult livestock may be infected and 46% of dogs.6 Practices that facilitate transmission of the parasite include feeding dogs with infected offal or discarding infected offal in the field where dogs can have easy access to it. In areas with no control programs, livestock is commonly slaughtered in open areas where there is no veterinary supervision.7

Alveolar hydatid disease is caused by E. multilocularis, which has an extensive geographical range in the northern hemisphere. The natural cycle involves foxes and small rodents as final and intermediate hosts, respectively. E. multilocularis is endemic in the central part of Europe, parts of the Near East, Russia, and the central Asian republics, China, northern Japan, and Alaska.6 Recent surveys in central Europe have extended the known distribution of E. multilocularis from four countries at the end of the 1980s to 11 countries in 1999, although the annual incidence of disease in humans remains low.9 There is evi-dence of parasites spreading from endemic to previously nonendemic areas in North America and on the north island, Hokkaido, of Japan, due principally to the movement or relocation of definitive hosts, foxes and coyotes. In North America the parasite has been recorded in two distinct geographic regions: the north tundra zone (western Alaska) and central North America.9,10 Despite the presence of infected definitive and intermediate hosts in 12 of the states in central North America, only one human case of alveolar echinococcosis has been described in Minnesota.11

China is a newly recognized focus of alveolar echinococcosis (AE) in Asia. E. multilocularis occurs in three areas: northeastern China including Inner Mongolia Autonomous region and Heliongjiang Province; central China including Gansu Province, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Sichuan Province, Qinghai Province and Tibet Autonomous Region; northwestern China including Xingjian Uygur Autonomous Region.12 The highest prevalence of AE in the world was found in Qinghai Province with 800 infections per 100 000 inhabitants.13

The infection of humans by the larval E. multilocularis is often the result of association with dogs and perhaps cats that have eaten infected rodents. Until recently, certain villages within the zone of tundra were hyperendemic foci because of the close interaction between dogs and wild rodents that live as commensals in and around dwellings; however, transmission has declined as a result of improved housing and control measures. In central Europe, rodents inhabiting cultivated fields and gardens become infected by ingesting embryophores expelled by foxes and, in turn, may be a source of infection for dogs and cats. A recent case-control study demonstrated a higher risk of alveolar hydatidosis among individuals who owned dogs that killed game, dogs that roamed outdoors unattended, individuals who were farmers, and individuals who owned cats.14 In rural regions of central North America, the cycle involves foxes and rodents of the genera Peromyscus and Microtus. Allowing pet dogs and cats in these regions to prey on local rodents may be hazardous.

Polycystic hydatid disease, caused by E. vogeli, has been reported infrequently from Central and South America. The natural hosts of this cestode are the bush dog, Speothos venaticus, and the paca, Cuniculus paca.1 The larval stage occurs occasionally in rodents or other species. Little is known of the epidemiology of polycystic hydatid disease. The natural final host of E. vogeli, the bush dog, is a wary and rarely seen animal that is an unlikely source of infection for humans. The intermediate host, the paca, is widely hunted for food in northern South America and local hunters routinely feed the viscera of pacas to their dogs; thus, infected dogs may be the primary source of infection for humans.15

Clinical Manifestations

Cystic hydatid disease

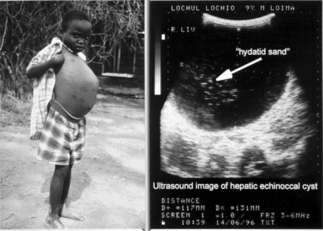

In humans, hydatid cysts of E. granulosus are slowly enlarging masses comparable to benign neoplasms; most human infections remain asymptomatic. Hydatid cysts are frequently observed as incidental findings at autopsy at rates much higher than the reported local morbidity rates. The clinical manifestations are variable and are determined by the site, size, and condition of the cysts.16 Hydatid cysts in the liver and the lungs together account for 90% of affected localizations. The average liver-to-lung infection ratio varies from 2.1:1 in clinical cases to 6:1 and 12:1 in asymptomatic individuals with hydatid disease.17 The chronic signs of hepatic cystic echinococcosis include hepatomegaly with or without the presence of a mass in the upper right quadrant (see Fig. 28.3). Obstructive jaundice accompanied by symptoms such as mild epigastric pain, indigestion, and nausea may occur occasionally. Cysts may also become secondarily infected with bacteria and manifest as an abscess. Features of lung involvement include coughing, hemoptysis, dyspnea, and fever. In about 10% of cases the cysts occur in organs other than the lungs and liver. Other known complications include anaphylaxis, secondary spread following rupture, pathological fracture of bones and formation of hepatopulmonary fistulae.18 The northern form (G7 genotype) causes a milder form of the disease with cysts usually localized in the lungs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree