Chapter 8

Early Detection Strategies

THE NEXT BEST THING TO PREVENTING CANCER is catching it early, when it’s more likely to be cured. That’s why surveillance is so important. It doesn’t prevent cancer or reduce risk, but if a tumor develops, surveillance offers the opportunity to find it before it spreads.

High-Risk Surveillance for Breast Cancer

Routine cancer screenings recommended for the general population aren’t adequate for high-risk women, who

• tend to develop breast cancer when younger, before routine screening in the general population begins.

• need screening beginning at a younger age, when breasts are more dense and mammography is less effective.

• have a higher lifetime risk for cancer.

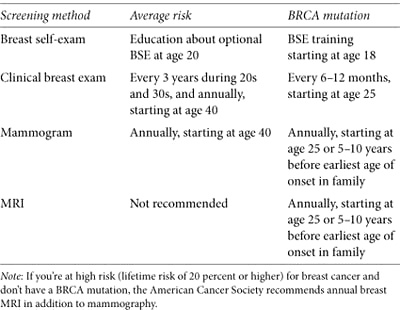

If you have an elevated risk for breast cancer and still have your natural breasts, your screening repertoire should include all the actions listed in table 7.

The Vocabulary of Screening

Scientists use certain criteria to describe the utility of screening tests. Sensitivity is the probability of a true positive test among those who have the disease—if two women in a group of one hundred have cancer, a highly sensitive test would correctly identify both. A highly sensitive test doesn’t miss many cancers, though it’s more likely to identify normal tissue as suspicious (false-positive), leading to more unnecessary biopsies. Specificity is the probability of a true negative test among those who don’t have the disease. A highly specific test correctly identifies normal tissue—if only two women in the group of one hundred have cancer, yet ten falsely test positive, the test isn’t very specific. A highly specific test is less likely to produce false positives, but it may also miss more cancers. The ideal test is both sensitive and specific—if someone tests positive, they have the disease. If they test negative, they don’t. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to develop the ideal test, and screening methods usually compromise one quality or the other.

Table 7. NCCN guidelines for breast cancer surveillance

Breast Exams

You and a healthcare professional should carefully examine your breasts for changes and abnormalities. Performing routine breast self-exams (BSE) has long been recommended. It may cause false positives—women who practice regular BSE have more biopsies for benign lumps than women who don’t. Many women, particularly those at high risk, discover their own early stage breast tumors during BSE or while dressing, showering, or bathing. A Harvard study found that 71 percent of women diagnosed with breast cancer at age 40 or younger discovered their breast cancers by self-exam.1 Duke University researchers demonstrated that BSE can detect new breast cancers in high-risk women: “Our results provide evidence that BSE should not be abandoned as an adjunct for breast cancer education, as well as a surveillance tool for high-risk women.”2

Self-exams need to be done regularly and done well. It’s a good idea to have a healthcare professional show you how to do a BSE and review your technique to make sure you’re doing it correctly. The Susan G. Komen for the Cure website (www.komen.org) has a good instructional video. Become familiar with the landscape of your breasts, both on the surface and the underlying tissue, so you’ll know if something feels or looks different. Examine your breasts at the same time each month a few days after your period or, if you’re postmenopausal, on the same day each month.

A clinical breast exam (CBE) is performed by your primary doctor (usually during your annual physical), a gynecologist, or another healthcare professional. You might wonder why you should bother with monthly BSE if a doctor is going to examine your breasts anyway. While a CBE is an important part of your screening regimen—it’s an opportunity for an expert to detect any suspicious breast changes—it only occurs twice a year. You, on the other hand, have twelve opportunities in the same period to find anything unusual. Used alone, CBE is a somewhat ineffective method of finding breast cancer. Combining self-exams, mammography, and MRI improves the odds of finding early tumors.

Mammograms

Overall, mammography is an effective tool for identifying early stage breast cancer. Mammograms use low-dose x-rays to produce images of the internal breast structure, often finding microcalcifications, tiny calcium deposits that may precede a tumor long before it can be felt. Mammography isn’t a perfect technology. It misses some breast cancers (false negatives), especially in younger women with dense breasts, and it isn’t highly sensitive. It frequently identifies suspicious changes that create anxiety, require biopsies, and turn out to be noncancerous (false positives). If you’re unfamiliar with mammograms, you’ll find a helpful video at www.mayoclinic.com (search for “mammogram video”).

MY STORY: Mammography Saved My Life

A mammogram found my breast cancer at age 40. My tumor was just 1.7 cm and couldn’t be felt by me or my surgeon. Without that mammogram, my cancer would have gone undetected. More than likely, it would have spread to my lymph nodes and who knows where else.

—SHAWN

If you’ve ever taken photographs with film then upgraded to a digital camera, you can appreciate the difference between traditional and digital mammography, a newer technology that produces instant, sharper computerized images that can be enlarged to more easily spot breast abnormalities. It’s more sensitive than standard mammography, so fewer women need to repeat the process. It’s also safe. Digital mammography emits up to 50 percent less radiation, although the amount in newer film mammography is also quite small. In a large clinical trial sponsored by the National Cancer Institute, both technologies performed equally well among 50,000 U.S. and Canadian women who showed no signs of breast cancer. Digital mammography was significantly better at screening women who were under age 50, who were of any age with very dense breasts, or who were premenopausal or perimenopausal at any age (women who had a last menstrual period within twelve months of their mammograms).3 Some of the 10,000 U.S. facilities that now use conventional mammography are converting to digital technology, but it will be some time before it’s widely available.

Mammograms for Women under Age 30

Being at high risk means you’re more likely to develop breast cancer at a younger age than other women, so it makes sense to begin having mammograms sooner. How early is too early? NCCN high-risk guidelines suggest starting at age 25 or five to ten years before the earliest onset in your family. Some experts propose that the increased lifetime exposure to radiation from starting annual mammograms before age 30 could lead to slightly increased breast cancer risk. It’s unclear to what extent risk is increased, and little long-term research is available on the effects of radiation in BRCA mutation carriers. When researchers addressed this issue with mathematical computer models, they calculated that for every 10,000 women between ages 25 and 30, early mammograms would save twelve or fewer lives, while the radiation received might cause about fifty-one breast cancer deaths ten or more years later. The effect was reversed among BRCA carriers age 30 and older: mammograms were estimated to save more lives than would be lost to radiation-induced breast cancers.4 More research is needed to better determine the benefits and risks of mammography in young women with mutations.

Mammograms for Women over Age 65

One revealing study comparing ten years of Medicare data showed that women are less likely to have mammograms as they get older.5 Study authors surmised that doctors less frequently recommend routine mammograms for older women, who often seek health care for specific problems, rather than for prevention. Even though much of a previvor’s cancer risk occurs before age 50, it persists throughout life. So it’s important to remain vigilant and continue having routine mammograms—they’re particularly good at identifying older women’s breast cancers—especially if you’re at high risk.

Mammograms after Breast Cancer

If you had breast cancer that was treated with radiation or chemotherapy, your doctor will probably recommend a new baseline mammogram six months after your final treatment, then annually thereafter. Some doctors recommend mammograms at six-month intervals for two or three years following radiation. If you’ve had one breast removed, you need annual mammograms of your healthy breast to address your increased risk of developing another breast cancer. Experience counts! Check the U.S. Food and Drug Administration mammography facility database (www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfMQSA/mqsa.cfm) to verify that your mammogram facility is FDA certified. Most doctors don’t recommend mammograms after bilateral mastectomy, whether or not your breasts are reconstructed, because almost all of your breast tissue is gone.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI uses magnetic fields and radio waves instead of radiation to produce hundreds of detailed images of the breast from several angles. Specially designed breast MRI machines produce the best images (some facilities don’t have them). Breast MRI is different than MRIs used to scan the head or chest and may be particularly good at finding cancers missed by mammograms, especially in premenopausal women. MRI is sensitive, so it’s also particularly good at finding abnormalities, including those that prove to be benign, which means it’s less specific than other breast cancer tests. Even though a biopsy is required to prove that an abnormality is benign, experts believe the benefit of MRI outweighs the downside for high-risk women. When an MRI detects an abnormality that can’t be seen by mammography or ultrasound, a special MRI-guided biopsy is required. Traditional biopsy methods aren’t effective, yet not all facilities that offer breast MRI have MRI-guided biopsy. Before you make an appointment, ask how many breast-screening MRIs a facility has performed, what their biopsy recommendation rate is, and whether they can perform MRI-guided biopsies if your screening finds something suspicious.

According to the American Cancer Society, you’re considered high risk if your lifetime odds of developing breast cancer are estimated to be 20 percent or greater. It’s an important distinction, because it means you should have breast MRIs in addition to the routine mammograms suggested for women of average risk. Having a BRCA mutation, a family history of breast cancer, or another hereditary syndrome meets the high-risk criteria.

Comparing MRI and Mammography

Most studies find MRI to be more sensitive, yet used together, mammograms and MRI are complementary, with each finding some cancers missed by the other. According to research, adding MRI to mammography improves sensitivity from 40 to 94 percent for finding cancer in young high-risk women.6 MRI is also good at finding early cancers in premenopausal, high-risk women whose younger, dense breast tissue can obscure mammography images. If MRI finds more tumors in high-risk women, why isn’t it the hands-down screening technology of choice? Mammograms have a distinct advantage: they pick up more microcalcifications that may be DCIS. Although imperfect and less sensitive, they’re more widely available, less expensive, and produce fewer false positives.

The Future of Breast Cancer Screening?

Digital tomosynthesis uses x-rays to create computerized three-dimensional pictures of the breast. A woman is positioned as though she will have a mammogram, and an x-ray tube quickly takes pictures from different angles as it moves around her breast. Scientists hope digital tomosynthesis will eliminate the sensitivity and specificity shortcomings of mammograms and MRIs. Two other experimental techniques are also promising. Molecular breast imaging, or breast-specific gamma imaging, uses a radioactive tracer injected into a vein to highlight any cancerous areas in the breast. Another procedure, positron emission mammography, detects even very small lesions by tracking sugar as it’s metabolized by tumors. Both processes may reduce the need for redoing images and lower the biopsy rates associated with MRI. Unlike MRI, both involve exposure to radiation. All three procedures are currently limited to research.

High-Risk Surveillance for Ovarian Cancer

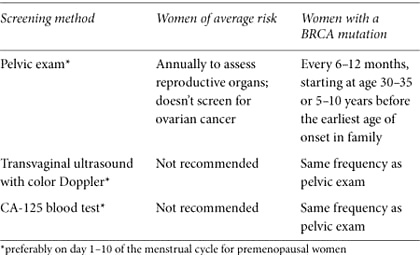

We have no self-exam or “mammogram” to find early stage ovarian tumors, and contrary to common belief, Pap smears don’t screen for this disease. Because no current test reliably detects ovarian cancer, no screening guidelines exist for symptomless women in the general population, where the risk of ovarian cancer is low. NCCN guidelines for high-risk women include those listed in table 8.

Table 8. NCCN guidelines for ovarian cancer surveillance

Pelvic Exam

A pelvic exam checks for abnormalities of the reproductive system. It should include a rectovaginal exam: the healthcare provider feels the ovaries by inserting a gloved, lubricated finger into the rectum and another finger into the vagina at the same time using the other hand to press on the abdomen. As uncomfortable as it may sound, the exam shouldn’t be painful. It’s the best way to feel the position, size, and shape of the ovaries. A pelvic exam might pick up an abnormality that could indicate cancer, even though it’s not sensitive or specific enough to identify ovarian cancer with certainty. Nevertheless, it should be part of a thorough exam for all adult women, no matter what their risk.

Transvaginal Ultrasound with Color Doppler

Transvaginal ultrasound uses a small probe inserted into the vagina to look for abnormalities of the ovaries, tubes, and uterus. A large study of ultrasound screening in high-risk women showed that most ovarian cancers were diagnosed at stage 3 or higher. All the women had normal scans during the previous year, leading researchers to conclude that ultrasound doesn’t dependably identify early stage ovarian cancer.7 Retrospective research of ovarian cancer that was detected by screening concluded that high-grade serous ovarian tumors (the type that usually develops in BRCA carriers) are more likely to be diagnosed only after they have advanced. Even though transvaginal ultrasound isn’t highly sensitive or specific and can lead to unnecessary surgery, experts recommend it for high-risk women who still have their ovaries.

CA-125 Blood Test

CA-125 is a blood protein that is sometimes elevated when a woman has ovarian cancer. After a diagnosis, a CA-125 test is used to monitor response to treatment. Once treatment is completed, the test helps to determine whether the cancer has returned. As a method of routine screening, CA-125 produces less than optimal results in most women: about 50 percent of women with early stage ovarian cancer and 20 percent who have advanced disease don’t have elevated CA-125 levels.8 Liver disease, uterine fibroids, other benign conditions, or other cancers can also raise CA-125 levels, especially in premenopausal women, making the test difficult to interpret, producing false positives, and requiring surgery to confirm a diagnosis. Undependable for most women, CA-125 combined with transvaginal ultrasound may find some ovarian cancers before symptoms appear and is recommended for high-risk women. Researchers are trying to determine whether measuring CA-125 levels every three months in high-risk women improves the test’s sensitivity and specificity.

Biomarkers for Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer

We’ve mapped the human genome and identified many disease-causing gene mutations. The next step in our quest for early detection is searching for other biomarkers, biological indicators of disease. Figuring out which biomarkers signal different cancers and developing a test to measure them would improve surveillance of early stage tumors. Sounds easy. It isn’t. CA-125 is a good example. We know it’s a biomarker for ovarian cancer, yet the current test doesn’t accurately determine who has the disease and who doesn’t. Combining CA-125 tests with other biomarkers could improve both the sensitivity and specificity of detecting ovarian cancer. The false-positive concern—needing surgery to follow up on a suspicious test result that may prove false—remains a large hurdle. New discoveries are bringing us closer to the answers we need to develop a dependable surveillance method for ovarian cancer.

What should sensitivity and specificity standards be for previvors, who have a higher prevalence of ovarian cancer than the general population? The answer may depend on your age, personal circumstances, and tolerance for potential false positives. If you’re already considering prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy (removal of your ovaries), you may be willing to trade specificity for increased sensitivity; you might worry more about missing an existing ovarian cancer than receiving a false-positive result. We desperately need a dependable way to find early stage ovarian cancer. In medicine, there’s always a need to strike a balance between making something available because we need it now and ensuring it stands up to the rigors of good scientific research. Researchers continue to work to identify tests that can accurately detect early stage ovarian cancer.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree