© Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015

Lisa A. Newman and Jessica M. Bensenhaver (eds.)Ductal Carcinoma In Situ and Microinvasive/Borderline Breast Cancer10.1007/978-1-4939-2035-8_88. Ductal Carcinoma In Situ Treated with Breast-Conserving Surgery Alone

(1)

University of Michigan Health System, Comprehensive Cancer Center, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, 48109 Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Keywords

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)Breast-conserving surgeryRadiation therapyBackground

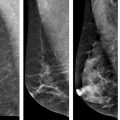

With the adoption of screening practices, the past three decades have seen an increased incidence of early stage breast cancer and a shift in the clinical presentation of breast cancer from large palpable tumors seen in the 1970s to pre-clinical mammographic detection today. This has also resulted in the evolution of the surgical management of early stage breast cancer. By the early 1990s, with release of the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) B-17 trial that specifically looked at excision versus excision plus radiotherapy (RT), breast-conserving therapy (BCT) joined mastectomy as a standard of care breast cancer surgery management option. [1].

Data from high-quality prospective randomized trials and from population-based retrospective studies support that RT following breast-conserving surgery (BCS) lowers the relative risk of local recurrence (LR) of both invasive and in situ disease, similarly across all DCIS subgroups (those perceived as low, moderate, and high risk) [2]. As discussed in other chapters, there are four major prospective randomized trials including NSABP B-17, the European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) 10853 trial, the Swedish Breast Cancer Group (SweDCIS), and UK Coordinating Committee on Cancer Research (UKCCCR); which together—along with their follow-up reports—have established the role of RT after BCS to reduce the risk of LR consistently across a wide spectrum of clinical and pathologic baseline characteristics [1, 3–9]. Comparing excision alone to excision plus RT, NSABP B-17 revealed a decrease in ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence (IBTR) risk from 16.4 to 7 % at 5 years, 32 to 16 % at 12 years, and 35 to 19.8 % at 15 years [1, 5, 9]. With the addition of RT to BCS, EORTC 10853 reported decrease from 26 to 15 % at 10 years, SweDCIS revealed 22 to 7 % at 5 years, UKCCCR reported 14 to 6 % of IBTR at 4.5 years [7, 10, 11]. A meta-analysis published in 2007 of these trials concluded the RT lowers the relative risk of both invasive and in situ IBTR by 60 % (40–67 % of invasive recurrence, 47–69 % for in situ) [12]. Furthermore, a 2010 meta-analysis by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group reported a 15.2 % absolute risk reduction of IBTR with the use of adjuvant RT [13]. Lastly, two population-based prospective studies further supported these findings. Warren et al. looked at a population-based sample from 1991 to 1992 and found that these prospective trial findings do extend to the community setting [2, 14]. A second by Smith et al. examined a SEER cohort of patients both with and without high-risk features from 1992 to 1999 and noted a 5-year event risk benefit from RT in both groups [15].

Clearly, the benefit of RT for decreasing IBTR is well established; however, none of the four prospective studies showed an overall survival benefit, and there was no decrease in metastatic recurrence. This finding was supported by the 2007 meta-analysis and the 2010 meta-analysis which reported a breast cancer-specific survival (BCSS) rate of approximately 95 % at 10 years [12, 13]. These facts posed the question of whether RT should be a standard component of treatment. Are there patients for whom omission of RT is reasonable? This chapter aims at: (1) reviewing the studies done in attempt to validate BCS alone and (2) to disclose the current status of BCS alone as an option.

Concern for Overtreatment

The subject of overtreatment of DCIS with RT has been a heavily debated topic over the past 20 years, with many retrospective analyses arguing that there are certain low-risk subsets of DCIS patients that may appropriately be treated with BCS alone [16–23]. Proponents of BCS alone argue that with no survival benefit, omission of RT will help spare these particular patients the morbidity of RT without sacrificing any meaningful clinical outcome [2]. Furthermore, there is also an argument of absolute versus relative risk reduction in these certain perceived low-risk groups (low grade, small size, advanced age) [21]. Taking all of this into account, the attempt to guide utilization of RT based on individual patient characteristics sounds reasonable; however, there are no data to support this practice as reproduction of the retrospective studies’ findings in prospective trials has been a challenge and has ultimately resulted in conflicting evidence [2].

Endorsing Omission of Radiation

Early Retrospective Studies

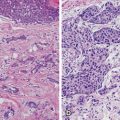

The practice of BCS alone for DCIS treatment can be traced back as far as the early 1970s to Lagios et al. who, to date, have some of the lowest published LR rates reported for excision alone [16, 17, 24]. Their criteria for excision alone were strict: low-grade disease, not greater than 25 mm, discovered mammographically, and excised with at least 1 mm margins. Their findings revealed a 12 % IBTR rate at 5 years and 16 % at 10 years, with no breast cancer-related deaths and no systemic recurrences [25].

Following the 1993 NSABP B-17 publication, many attempts were made to identify low-risk patients with DCIS and to validate the safety of BCS alone as treatment for these patients. In 1996 (as thoroughly discussed in Chap. 18), Silverstein et al. introduced the Van Nuys Prognostic Index (VNPI) , a retrospective, single-institution series, with the purpose of guiding treatment recommendations from a prognostic score acquired from a combination of variables (tumor size, grade, margin width, and the presence or absence of comedonecrosis) [26]. In the original cohort of 330 cases, a VNPI of 3 or 4 was considered low risk. The 8-year recurrence-free survival rate for this subgroup was 97 % compared to 77 % for VNPI score of 5–7 and 20 % for 8 or 9. Silverstein et al. followed this up in 1999 by looking at 93 low-risk patients treated with BCS alone, with a margin width of at least 1 centimeters, and reported a 8-year IBTR risk of 3 % [23]. It is worth noting, although still less than 15 %, at 12-year follow-up and with expansion of the cohort to 212 patients, the IBTR risk significantly increased to 13.9 % (10.5 % DCIS, 3.4 % invasive) [2, 22]. The VNPI was expanded in 2003 to the University of Southern California/Van Nuys Prognostic Index (USC/VNPI) by adding age to the variables [20]. At its publication, the study reported that by using the USC/VNPI to identify low-risk patients, BCS could be safely omitted with a 12-year IBTR probability of 6 % or less. Then, in 2011, when genomic grade index was incorporated, the results showed improved prognostic value, especially for predicting early relapse [27].

These encouraging results, however, are all based off of single-institution, retrospective data. As discussed further in this chapter, a handful of prospective randomized trials and a population-based cohort study have been performed in attempt to further validate this; unfortunately the data has not been conclusive. These studies are discussed below.

Prospective Trials and Population-Based Study

Wong et al. and researchers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute opened a prospective phase II clinical trial in 1995 looking at women with low or intermediate nuclear grade DCIS, not greater than 25 mm in size, with margins of at least 10 mm or negative re-excisions, treated with BCS alone (no RT, no endocrine therapy) [28] . During the trial, at a 3.6-year median follow-up, the 5-year LR rate was found to be around 12 %. Because NSABP B-17 revealed that the recurrence rate could double between years 5 and 12 (16.4 vs. 7 % at 5 years to 32 vs. 16 % at 12 years), there was concern that the long-term recurrence risk may approach 24 %; therefore, the trial was closed prematurely in 2002 [1, 29]. The initial results were published in 2006 with an 8-year follow-up in 2013 that revealed a 10-year estimated cumulative incidence of LR of 15.6 % (11-year median follow-up) [30]. This led to the authors’ conclusion that even patients with favorable DCIS maintain a substantial and ongoing LR risk when treated by BCS alone.

The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) ran a phase II prospective study from 1997 to 2002 that looked at two groups of patients, those with low- or intermediate-grade DCIS less than 25 mm and those with high-grade DCIS less than 1 cm [31]. All participants had negative post-lumpectomy mammograms and at least 3 mm margins. Starting in 2000, tamoxifen was allowed but not randomized. A 5-year IBTR risk in the low-to-intermediate-grade group (median follow-up of 6.2 years) was reported as 6.1 % (95 % CI, 4.1–8.2 %) and in the high-grade group (median follow-up of 6.7 years) of 15.3 % (95 % CI, 8.2–22.5 %). In reference to the NSABP B-17 data suggesting a potential doubling of the recurrence risk between 5 and 12 years, in the low-to-intermediate-grade group, the risk should still remain less than 15 % [2]. The authors concluded low-to-intermediate-grade DCIS cohort had an acceptably low rate of 5-year IBTR; however, with high-grade lesions, the higher rate of 5-year IBTR suggests excision alone is inadequate treatment.

The Radiation Therapy and Oncology Group (RTOG) opened RTOG 98–04 in 1998, a prospective study to compare BCS alone to BCS with RT. Trial candidates had mammographically detected low- or intermediate-grade lesions, with a minimum of 3 mm margins (tamoxifen was left to the discretion of the treating physician). Patients were randomized to BC plus RT or to BCS alone. The median follow-up was 6.46 years. The trial unfortunately closed prematurely in 2006 due to poor accrual; however, the initial results of those enrolled were reported in 2011 [32]. Local failure at 5 years was 0.4 % for women treated with radiation versus 3.2 % of women who were observed. Size, grade, margin status, and age had no impact on local failure.

In summary, the prospective randomized studies looking at low-risk subgroups by Wong et al., ECOG, and RTOG, reported the 5-year IBTR risk as 12, 6.1, and 3.2 %, respectively, in low-risk DCIS patients [28, 31, 32]. The 10-year IBTR risk in the Wong et al. group was 15.6 % [30]. It is again worth noting that tamoxifen was allowed but not randomized in the ECOG trial. In the RTOG trial, the use of tamoxifen was left up to the discretion of the treating physician.

More justification for RT omission was attempted by a retrospective study of a population-based cohort treated by excision alone from 1983 to 1994 in the San Francisco Bay Area [33]. At a 6.4-year median follow-up, there was a 20 % IBTR risk; however, patients with low-grade DCIS and a margin of at least 1 cm revealed a 9 % IBTR risk. Multivariate analysis revealed grade and margin status as factors associated with a higher risk of IBTR. High-grade lesions were five times more likely to recur and margins less than 1 cm were three times more likely to recur. This 9 % IBTR risk at 6.4 years suggests the prospective trial findings to extend to the community; however, it is worth mentioning again that this is early follow-up and long-term efficacy needs to be established as both prospective and retrospective trials discussed previously showed significant increase in incidence at longer follow-up.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree