Introduction

There are two possible definitions of ‘drug misuse’. The first, obvious, definition is ‘drug abuse’ with the term ‘drug’ used to cover illicit substances, but also non-compliant use of prescription drugs such as psychotropic medications and opioids. This drug abuse, which is not peculiar to older people, results from a complex interaction between a substance, a patient and its environment. However, older people are also exposed to another great danger: adverse drug reactions, with the term of ‘drug’ used to cover licit medication prescribed in agreement with basic medical rules. Here comes the second definition. Avoidable adverse drug reactions result from another interaction, as complex as the first one, involving a substance, a patient and its environment and the medical practitioner. For dementia, it could be even more complex, in part because of cognitive disorder, but also because of another factor that should be taken into account: the professional or informal stakeholder. For example, this one could ask for sedative medication prescription, not only for the direct patient benefit but also for their own quality of life. Both definitions have several meeting points, in particular for psychotropic medications: addiction, dependence, abstinence syndromes and health problems. In both definitions, it is, in most cases, an inappropriate response to a real issue. Consequently, to limit avoidable adverse drug reactions, we need to greatly change the way in which we prescribe for older people.

Drug Abuse

For coverage on this subject, see Chapter 122, The use and abuse of prescribed medicines.

Medications and The Elderly: Geriatric Characteristics, Adverse Drug Reactions and Drug Misuse

Medications and The Elderly: Characteristics

Benefit–Risk Evaluation of Medications in The Elderly

The Elderly and Clinical Trials

Phase III

When a medication has been shown to be effective in the young adult, it is also conventionally accepted that it is generally effective in the elderly. However, such an assertion can be discounted. For example, O’Hare et al.1 carried out a literature review of the indications of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin II-receptor antagonists (AIIRA) in chronic kidney disease in the elderly. They came to the conclusion that the recommendations were based on data that are not relevant to the elderly, because of differences in the causes of chronic kidney disease. Similarly, the SENIORS study, performed to determine the effect of nebivolol as add-on therapy in elderly patients with heart failure, regardless of ejection fraction,2 found that, a priori, efficacy was lower than in the young adult.

Medication risks are very poorly evaluated before market authorization, for three essential reasons. First, non-inclusion in Phase III trials of subjects with several concomitant disorders and receiving several medications: very elderly persons are among the populations excluded from clinical trials, including trials that include patients over 65 years of age, if these subjects present comorbid conditions. Several years ago, attention was drawn to this point by international recommendations that have not yet been implemented. Second, inadequate collection of adverse effects is also a great limitation. Third, premarketing trials, although they can evaluate the efficacy of a medication in a controlled setting, only detect adverse drug reactions (ADRs) when these occur in more than one case in 100 and are not limited to a particular subgroup. This being so, they yield only relatively restricted information on safety of use (including in the young adult). The denominator of the benefit–risk balance in the elderly patient can only be known through information gained in Phase IV.

Phase IV

In the USA, over a 25 year period, 10% of new drugs were withdrawn from the market or were the subject of major alerts and half of the withdrawals occurred within 2 years of drug introduction.3

Through pharmacovigilance, Phase IV notably allows the collection of information on drug-related risk. However, spontaneous notification, which is the cornerstone of pharmacovigilance, principally yields information on type B adverse effects (bizarre or idiosyncratic effects, dose independent and unpredictable) and not on type A adverse effects (augmented pharmacological effects, dose dependent and predictable) which have the dual specificity of being more frequent and also of often being avoidable.

In Practice

As the complete information needed to determine the benefit–risk ratio in elderly patients is not available and as the treatment decision cannot be based only on expected efficacy, guidelines with regard to this frail elderly population are often based on low levels of evidence, notably concerning insufficiency of treatment (see the section Classification of the various types of suboptimal prescription) and so affect the expected benefit–risk ratio.

Age and Adverse Drug Reactions

Elderly persons may be more at risk of ADRs due to physiological age-related changes that influence the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of drugs.4 These reactions are more frequent after the age of 65 years. However, once confounding factors have been taken into account, age does not seem to be an independent risk factor for ADRs5 but it is a factor of gravity of such events.

Polypharmacy and Adverse Drug Reactions

Polymorbidity leads to polypharmacy, which may be expected to yield certain benefits. However, polypharmacy, because of disease–disease and drug–disease interactions, may in fact decrease the benefit–risk balance of the treatments given. There are two possible definitions of polypharmacy.6 The first is concomitant use of several medications. However, although some investigators used a threshold of 3–5 medications, no exact figure has been clearly established. A second definition is overuse or use of more medications than is clinically necessary (see the section Classification of the various types of suboptimal prescription). This definition carries the negative connotation of suboptimal prescription, but without fixing an arbitrary threshold.

Polypharmacy (in the sense of the total number of medications taken) is an independent risk factor of iatrogenic events that is constantly found in the literature. In a study by Gallagher and O’Mahoney, patients taking more than five medications were at greater risk of hospital admission because of inappropriate prescription.7 Mackinnon and Hepler developed a set of indicators of avoidable ADR8 and applied it retrospectively to a hospital database.9 One of the main risk factors was found to be the number of medications (>5). A recent review of the literature showed that polypharmacy is increasing and is a risk factor for morbidity and mortality.10 The use of an arbitrary number as a cut-off is, however debatable. Viktil et al.11 carried out a hospital-based multicentre prospective study of 827 patients, aiming to determine whether polypharmacy defined as a given number of drugs is a suitable indicator for describing the risk of ADRs. The number of ADRs per patient increased in an almost linear manner with the number of medications at admission. One unit increase in number of drugs increased the incidence of ADRs by 8.6% [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.07–1.10]. The most appropriate definition of polypharmacy in geriatrics therefore seems to be the accumulation of medications considered useless and/or likely to lead to drug interferences.

Several studies found an association between the number of medications and use of inappropriate medications,12 including an important retrospective study of 2707 elderly patients receiving home care in eight European countries.13

Disease–Drug Interactions, Risk Factors for Iatrogenic Events

In this section, we will not address ‘classic’ disease–drug interactions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and beta-blockers, which are not specific to geriatrics.

Some elderly persons are at increased risk of iatrogenic events. Some authors14 suggest that the following comorbid conditions should be considered as increasing the risk of ADR: frailty, renal insufficiency and cognitive impairment. As the incidence of ADRs is higher in women, female gender is a potential iatrogenic risk factor. In the study of Gallagher and O’Mahoney, for example, women were twice as likely as men to be admitted to hospital due to inappropriate prescription.7 With regard to comorbid conditions, an Australian cohort study found that cardiac failure, chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes, renal or liver failure, rheumatological disease and cancers were associated with greater risk of repeated admissions for ADRs.15 Mackinnon and Hepler, in their retrospective study,9 found that the number of comorbid conditions was among the main risk factors for avoidable ADRs.

With regard to cognitive impairment, publications are sparse. In a prospective study of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, medications were a contributory factor to admission in 25% of cases.16 In another French cohort17 of 80 patients with dementia, 37% of short-stay hospital admissions were secondary to an ADR and 57% of admissions were due to potentially avoidable ADRs. About 20% of the ADRs observed were falls and the medications most often involved were psychotropic agents. There appears to be an excess risk of iatrogenic events in persons with dementia. The extent of avoidable iatrogenic events and inappropriate prescriptions is still very poorly known in this population.

Drug–Drug Interactions

Use of several medications and more numerous comorbid conditions are associated with increased risk of a potential interaction.

Drug interactions in the elderly patient fall into three main categories.18 Conventionally, these involve drugs with a narrow therapeutic window such as digoxin, phenytoin and warfarin. These interactions are often well known, monitoring tests are available and they are detected by all prescribing software programs. The second category concerns complex interactions; patients with nine medications or more or with numerous comorbid conditions are often in this category. The choice of each medication in isolation is generally appropriate. The third category is the prescribing cascade: an ADR is interpreted as a new independent disease state for which another medication is prescribed and the patient is then susceptible to present with other ADRs because of this unnecessary medication. We can cite, as an example, patients receiving cholinesterase inhibitors who are more at risk of receiving an anticholinergic drug for new-onset incontinence.

A Swedish study of the elderly population showed an increase in polypharmacy and potentially clinically significant interactions between 1992 and 2002.19 The proportion of elderly persons exposed to potentially clinically significant interactions rose from 17 to 25% in the 10 year period.

Clinical Manifestations of Drug Interactions

A French study20 analysed for one year the medications taken by elderly patients admitted to a geriatric unit: of the 894 patients (89.4%) who took at least two medications, 538 (60.2%) were exposed to 1087 potential interactions. Clinical or biological effects were observed in 130 patients (14.5% of patients taking two or more medications). A review of the literature from 1990 to 2006 relating to drug interactions in the general population suggests that although potential drug interactions are frequent, they rarely lead to hospital admission. However, this rate seems to increase with age, rising from 0.57 to 4.8% of admissions of elderly patients.21 Juurlink et al.22 carried out a 7 year case–control study of all patients aged 66 years or over living in Ontario, Canada, and treated with glyburide, digoxin or ACE inhibitors. In the week before admission, patients receiving glyburide and admitted for hypoglycaemia were six times more likely to have taken cotrimoxazole, patients receiving digoxin admitted for ADR were 12 times more likely to have been treated with clarithromycin and patients receiving ACE inhibitors and admitted for hyperkalaemia were 20 times more likely to have been treated with a potassium-sparing diuretic.

In Practice

It is not realistic to think that physicians know and recognize all drug interactions. Prescribing software programs can help to reduce interactions but they raise the problem of numerous irrelevant alerts that are ultimately ignored by the prescriber, of significant but unrecognized interactions and updates that are not carried out. The problem is made more complex by the fact that it is difficult to know, among the potential interactions, which ones will be have a clinical expression. It therefore seems necessary to concentrate on monitoring the medications with a narrow therapeutic window, to look for potential interactions when a new co-medication is introduced and to consider the possibility of an ADR when in the presence of symptoms of recent onset, in order to avoid the prescribing cascade.

Medications and The Elderly: Iatrogenic Consequences

A large prospective study23 showed, in a population that was not specifically geriatric, a 6.5% prevalence of hospital admissions secondary to an ADR. The drugs most often implicated were low-dose aspirin, diuretics (27%), warfarin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). The most common reaction was gastrointestinal bleeding, which was responsible for half of the deaths due to ADRs. These results, however, have to be adjusted for the consumption rates of these drugs. The mean age of subjects admitted for ADRs was 76 years (compared with 66 years for all admissions). Of these ADRs, 72% were considered to be avoidable.

The rate of ADR-related hospitalization appears higher in elderly than in younger adults. A meta-analysis of 17 observational studies estimated the mean rate of ADR-related admissions in elderly subjects as 16.6%.24 A considerable proportion of these were judged to be avoidable. A cohort study of 30 397 persons followed for 1 year in an ambulatory setting found an overall rate of ADRs of 50 per 1000 patient-years, of which 27.6% were considered to be avoidable.25 More than one-third of these ADRs (38%) were judged to be severe, life-threatening or fatal and a higher proportion (42.2%) were avoidable. In an institutional setting, the incidence of ADRs varied according to the method of identification used, ranging from 1.19 ADRs for 100 patient-months to 7.26 ADRs for 100 patient-months with a computerized detection system.26 Between 10 and 45% of the ADRs were considered severe.

Finally, ADRs are a frequent, or even the most frequent, cause of hospital admissions in the elderly. One-third to half of these reactions are severe and on average half could have been avoided.

Medications and The Elderly: Drug Misuse or Suboptimal Prescribing

Classification of the Various Types of Suboptimal Prescription

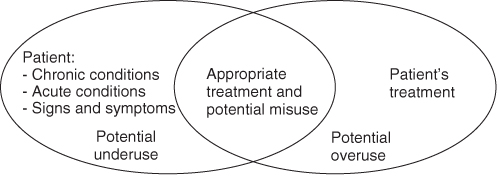

The appropriateness of prescription reflects its quality. Terms such as optimal or suboptimal may also be used. Several types of suboptimal prescription in elderly subjects are classically described: excess treatment (overuse), inappropriate prescription (misuse) and insufficient treatment (underuse).6 The indicators defined in Anglo-Saxon countries for assessing prescription quality for the elderly generally employ these three types. To sum up, for a given patient, certain treatments can be considered inappropriate and others insufficiently prescribed. Although it is legitimate in a quantitative approach to seek to reduce the number of medications taken by a patient, close qualitative analysis cannot be dispensed with. For this reason, the number of medications is not a good judgement criterion.

Excess Treatment or Overuse

This concerns the use of medications prescribed in the absence of an indication (the indication has never existed or no longer exists) or prescription of medications whose efficacy is not proven (insufficient medical service rendered).

Inappropriate Prescription or Misuse

This relates to use of medications whose risks exceed the expected benefits. This concept was first introduced by Beers, who established a list of drugs to avoid. The list has since been adapted for ambulatory patients and updated.27

Insufficient Treatment or Underuse

This is defined as the absence of initiation of an effective treatment in subjects with a condition for which one or several drug classes have demonstrated their efficacy.

As the frail elderly are generally excluded from clinical trials, a drug–indication pair must fulfil several conditions in order to comply with the definition of underuse:

- It must have a benefit–risk balance that is unquestionably favourable in a population of robust younger adults.

- This benefit, observed in a robust subject, should a priori be found in an elderly subject.

- It must not present major excess risk in the frail elderly population (which means that safety data on its use after marketing authorization need to be available).

- It should, to some extent, have been the object of clinical studies revealing increased overall mortality in undertreated patients, but these are observational data that are generally biased.

Four risks can easily be identified:

Relations Between the Different Types of Suboptimal Prescription (Figure 121.1)

A medication may be underprescribed, for example antidepressants in atypical depression of the elderly person, and at the same time could raise the problem of inappropriate prescription, such as when antidepressants are prescribed for life after an episode of reactive depression.

A study by Steinman et al.28

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree