Distal Pancreatectomy

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Proximal Parenchymal Transection and Retroperitoneal Dissection

Radical Lymphadenectomy

Resection of Adjacent Organs, Superior Mesenteric Vein/Portal Vein, and/or Celiac Axis

1. PROXIMAL PARENCHYMAL TRANSECTION AND RETROPERITONEAL DISSECTION

Recommendation: The pancreatic parenchyma should be transected proximal to all gross disease within normal-appearing gland. Confirmation of a margin-negative resection by intraoperative analysis of the pancreatic neck margin should be considered but is not obligatory, particularly if re-resection is likely to result in the sacrifice of a significant amount of normal pancreatic parenchyma. The posterior plane of the dissection should be carried deep relative to gross tumor and include a rim of normal tissue between the tumor and posterior dissection surface.

Type of Data: Primarily retrospective; two small single-institution prospective.

Strength of Recommendation: Weak.

Rationale

Most patients with tumors of the body or tail of the pancreas are not candidates for potentially curative surgery owing to the presence of either locally advanced or metastatic disease at the time of their initial presentation.1 Among patients who do undergo resection with curative intent, the 5-year overall survival rates range from 6% to 30% in small, single-institution series.2 A recent multicenter analysis of patients undergoing left pancreatectomy reported a median survival duration of 16 months and found that positive resection margins were independently associated with poorer survival.3

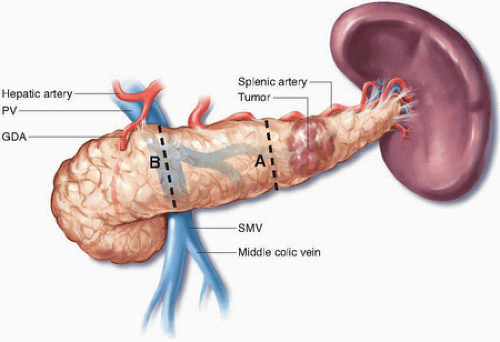

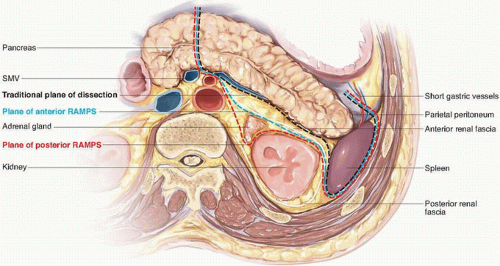

Classic distal pancreatectomy is characterized by the development of a posterior dissection plane between the pancreas and anterior renal fascia and parenchymal transection just proximal to the cancer (Figs. 15-1 and 15-2). The oncologic integrity of this approach has recently been questioned; of particular concern is the perceived inability of the operation to optimize rates of margin-negative resection given its limited proximal and posterior anatomic scope. The radical antegrade modular pancreaticosplenectomy (RAMPS) procedure, which was developed specifically to address this concern, epitomizes a more exhaustive local resection. In this operation, the pancreatic parenchyma is transected proximally at the neck of the gland (see Fig. 15-1), and the posterior dissection is performed in one of two planes, both of which lie deep to the anterior renal fascia, regardless of the posterior extent of the primary cancer.4 If a rim of normal pancreas lies posterior to the tumor, a superficial dissection just deep to the fascia on the surface of the left adrenal gland is performed (see Fig. 15-2). If the posterior aspect of the tumor contacts or breaks through the posterior capsule of the gland, an even deeper plane that includes the adrenal gland and Gerota fascia of the left kidney is dissected. In addition to facilitating the soft tissue clearance needed to maximize both R0 rates and nodal clearance, the proximal transection plane with proximal ligation of the splenic vessels has been suggested to reduce the risk for splenic vein thrombosis associated with more distal ligation of the vein.5,6

In a recent long-term follow-up study of 47 patients who underwent RAMPS at a single institution, the R0 rate was 81%, and the 5-year overall survival rate was 35.5%; other centers have reported similar outcomes.2,7 Although these numbers are favorable, they are difficult to interpret, particularly because the oncologic status of the tangential margins (i.e., the anterior and posterior surfaces) has been

rarely reported in other series of distal pancreatectomy.2 Two small studies comparing RAMPS to conventional distal pancreatectomy reported no difference in actuarial survival and mixed results with regards to achieving negative tangential and retroperitoneal margins.8,9 However, these studies were retrospective and underpowered, and further work is clearly needed to make any substantial conclusions.

rarely reported in other series of distal pancreatectomy.2 Two small studies comparing RAMPS to conventional distal pancreatectomy reported no difference in actuarial survival and mixed results with regards to achieving negative tangential and retroperitoneal margins.8,9 However, these studies were retrospective and underpowered, and further work is clearly needed to make any substantial conclusions.

The potential disadvantages associated with more radical soft tissue clearance must also be considered. RAMPS has been associated with a severe complication rate of 29%2; however, the extent to which these complications result from the more proximal parenchymal transection or deeper posterior dissection associated with the operation, rather than the more radical lymphadenectomy, is unclear. Furthermore, the risk for endocrine insufficiency, in particular, should be carefully considered prior to the resection of normal, functioning pancreatic parenchyma.10

Given the unclear advantages associated with uniform transection of the pancreas at the neck and a deep posterior dissection, the routine use of these techniques cannot be advocated at present. Instead, the pancreas should be divided proximal to the site of disease, and the posterior dissection should be carried out deep to the tumor, with a rim of grossly uninvolved soft tissue included both proximally and posteriorly. Although no data support the routine intraoperative evaluation of either the pancreatic neck margin or posterior surface, subjecting both to frozen section analysis would seem reasonable if there is additional soft tissue that could be re-resected if positive margins are found.

2. RADICAL LYMPHADENECTOMY

Recommendation: Lymphadenectomy performed as part of distal pancreatectomy for cancer should routinely include the nodal basins along the splenic artery, at the supra- and infrapancreatic border, and at the splenic hilum.

Type of Data: Primarily retrospective, low-level evidence.

Strength of Recommendation: Weak.

Rationale

Adenocarcinomas of the pancreatic body and tail frequently metastasize to regional lymph nodes. In cases of resectable adenocarcinomas of the body and tail, positive lymph nodes are found in 47% to 80% of resected specimens.11 Lymphatic spread appears to occur quite early, as reflected by the presence of lymph node metastases in more than 50% of patients with small cancers (<2 cm).12,13 Positive lymph nodes are associated with poor prognosis.14 Although a direct effect of lymphadenectomy on survival has not been established, resection of the regional lymph nodes should be performed for staging, if not for therapeutic purposes, as part of potentially curative resections of the pancreatic body or tail.15

Lymphatic drainage from cancers in the distal pancreas initially travels to a superficial ring composed of four groups of named nodes—the splenic, gastrosplenic, suprapancreatic, and infrapancreatic nodes—and then to a deeper group of nodes that includes the preaortic nodes, lateral aortic nodes, and interaortocaval nodes.16,17 In a recent study of 85 patients who underwent radical pancreatectomy with routine dissection of lymph nodes along the common hepatic artery, splenic artery, inferior edge of the pancreas, and splenic hilum and selective dissection of aortocaval nodes, metastases were identified in 5 of 60 (8.3%) common hepatic artery nodes, 19 of 70 (27%) splenic artery nodes, 5 of 31 (16%) nodes along the inferior edge of the pancreas, and 2 of 62 (3%) hilar nodes.14 Positive nodes were also found along the SMA (9 of 31 nodes, 29%) and celiac trunk (6 of 17 nodes, 35%). In another recent investigation of 1,461 lymph nodes resected from 50 patients at distal pancreatectomy, lymph nodes attached to the pancreas accounted for 78% of positive lymph nodes, and positive extrapancreatic lymph nodes were found in only 6.5% of patients in whom no positive lymph nodes were attached to the pancreas.18

Despite this general understanding of the anatomy of the lymphatics associated with the pancreatic body and tail, few data are available for guiding decisions regarding the extent of lymphadenectomy at the time of distal pancreatectomy.15,19,20 According to the American Joint Committee on Cancer, standard lymphadenectomy for cancers in the body and tail of the pancreas should routinely include lymph nodes along the common hepatic artery, celiac axis (CA), splenic artery, and splenic hilum.21 In practice, however, many surgeons perform a more limited lymphadenectomy that includes nodes above and below the body and tail of the pancreas but not nodes at the common hepatic artery or CA. Because no studies have compared survival or quality of life outcomes following more limited or extended resections, the benefits and costs associated with each extent of lymphatic resection is unclear. Given available data, however, it would seem

reasonable to remove at least the nodes along the upper and lower border of the pancreas, the nodes at the splenic hilum, and those along the splenic vessels (see Fig. 14-4).

reasonable to remove at least the nodes along the upper and lower border of the pancreas, the nodes at the splenic hilum, and those along the splenic vessels (see Fig. 14-4).

Technical Aspects

During lymphatic dissection for distal pancreatectomy, the draining lymphatics along the course of the major vasculature must be securely ligated. This can be accomplished using a variety of techniques. For the ligation of lymphatics along the leftmost border of the SMA and the CA, clips and sutures should be used to help decrease the incidence of postoperative chyle leaks. In general, the lymphatic basins are most readily dissected en bloc as part of the pancreatectomy, but this is not an essential requirement; if necessary, nodal basins along the celiac and SMA can be dissected separately.

Lateral Portion of the Dissection

Splenectomy to harvest lymph nodes in the splenic and gastrosplenic basins is mandatory for cases of pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic body or tail. Optimal harvest of the gastrosplenic nodes should be accomplished by dissecting the short gastric vessels in close proximity to the stomach, thereby leaving the maximum amount of fibrofatty tissue from the gastrosplenic ligament with the specimen.

Superior Portion of the Dissection

The suprapancreatic nodes run along the course of the splenic artery, so dissection directly along the course of the artery should not be conducted. Rather, the retroperitoneal fat along the cephalad aspect of the pancreatic tail and splenic artery should be resected en bloc with the tumor.

Inferior Portion of the Dissection

Ensuring inclusion of the infrapancreatic nodes in the specimen requires that dissection along the caudal aspect of the pancreatic body similarly not proceed directly on the substance of the gland itself. Rather, dissection should include some of the retroperitoneal fat in this location. Because the mesocolic nodes lie within the leaflets of the transverse mesocolon at its junction with the pancreas, the mesocolon should be separated off the gland in such a way as to include the most posterior of its attachments with the specimen.22

Medial Portion of the Dissection

As discussed, the role of resecting the nodes around the hepatic artery, celiac trunk, and SMA is unclear. When performed, lymphadenectomy of these basins is usually facilitated by identifying the proper hepatic artery and following it proximally towards the origin of the gastroduodenal artery. Ligation of the right gastric artery may be performed to facilitate the lymphadenectomy and to better visualize the anterior surface of the portal vein at the cephalad border of the pancreatic neck. The nodes along the hepatic artery, the left border of the portal vein, and the right crus are swept medially with the specimen until the origin of the splenic artery is identified. Once the splenic artery has been ligated and the celiac nodes have been dissected, the dissection continues posteriorly in a sagittal plane until the SMA is encountered.23 The proximal SMA can first be identified in the root of the mesentery just as it crosses the left renal vein.

3. RESECTION OF ADJACENT ORGANS, SUPERIOR MESENTERIC VEIN/PORTAL VEIN, AND/OR CELIAC AXIS

Recommendation: Extended operations that involve the resection of adjacent organs, a segment of the superior mesenteric vein (SMV)/portal vein (PV), or even the celiac axis (CA) concomitantly with distal pancreatectomy are occasionally justified in highly selected patients in whom a margin-negative resection is anticipated.

Type of Data: Primarily retrospective, low-level evidence.

Strength of Recommendation: Weak.

Rationale

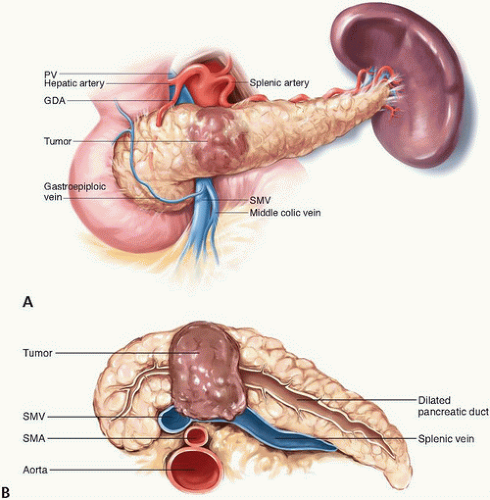

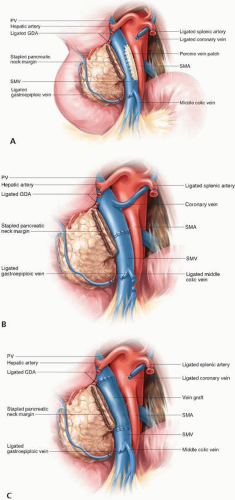

Because they do not cause symptoms until late in the disease course, tumors in the body and tail of the pancreas tend to be more advanced at presentation than tumors in the head of the pancreas. Nonetheless, the primary goal of potentially curative surgery for distal pancreas cancers is identical to that for pancreatic head cancers: complete extirpation of all disease to microscopically negative margins. Owing to the unique anatomic relationships of the pancreatic body and tail, resection to negative margins may require en bloc resection of the SMV/PV (Fig. 15-3A,B), adjacent organs, or even the CA in addition to the spleen.

Historically, extended operations for distal pancreatic cancers were considered uniformly inappropriate because the survival of patients with distal pancreatic cancer was so poor. However, recent series have demonstrated that extended operations may yield R0 resection and may be associated with rates of morbidity and long-term mortality that are higher than those associated with standard operations but still acceptable in a relatively small group of highly selected patients.1,24,25,26,27 In a series of 513 patients who presented to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center for treatment of an adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic body or tail between 1983 and 2000, the 5-year overall survival rate of patients who underwent extended distal pancreatectomy (22%) was similar to that of patients who underwent standard distal pancreatectomy (8%) and superior to that of patients who received palliative therapy. However, only 57 (11%) patients underwent resection, and of these patients, only 22 underwent extended operations.1 The infrequency with which extended operations were conducted even in this high-volume center notwithstanding, one can expect the number of patients who may reasonably be considered for these procedures to increase as novel systemic therapies increasingly prolong the survival of patients with localized pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and as preoperative therapy is increasingly used to select patients with biologically favorable tumors for increasingly aggressive operations. Nevertheless, given their technical challenges, extended operations of the distal pancreas, particularly those that require vascular resection, should be performed only at high-volume treatment centers by surgeons skilled in the techniques necessary for the procedures.

Technical Aspects

Superior Mesenteric Vein/Portal Vein Resection

In most cases, involvement of the SMV/PV confluence is evident from the findings of preoperative imaging studies. In some instances, venous involvement is evident by the surgeon’s inability to create a retropancreatic tunnel over the SMV/PV. Even if a tunnel is created, however, there may still be vein involvement at the left lateral aspect of the SMV/PV that will not be apparent until the neck of the pancreas is transected. If tumor involvement of the splenic vein extending to or beyond the vein’s confluence with the SMV/PV is present, a tangential or segmental resection of the involved portion of the SMV/PV is advised if a complete macroscopically negative resection is otherwise expected (Fig. 15-4A-C).

The remainder of the specimen is mobilized by dividing the lateral attachments of the spleen, the attachments of the body and/or tail of the pancreas, and any adjacent organs that may be involved. Such division may require the ligation of the inferior mesenteric vein if it inserts into the splenic vein. The specimen can then be elevated and retracted to the right to expose the SMA. The anterior and left lateral aspects of the SMA should be skeletonized and completely separated from the specimen. After this separation is complete, the specimen is entirely free except for the attachment at the vein.

FIGURE 15-4 Reconstruction of the portal vein or superior mesenteric vein may be accomplished using a patch venoplasty (A), primary end-to-end reconstruction (B), or interposition graft (C). |

The involved segment of the SMV/PV must be dissected circumferentially from the surrounding tissues, including the head of the pancreas, the uncinate process, and the retroperitoneum. The length of the involved segment of vein can then be assessed. If the involved segment of vein is short (<3 cm), the surgeon may perform maneuvers to maximize the possibility of a primary venous anastomosis. The falciform ligament should be completely divided to free the liver from the anterior wall and the peritoneal lining of the small bowel mesentery should be transversely incised to allow more upward mobility of the distal end of the vein. In addition, the middle colic vein (and the inferior mesenteric vein, if it inserts directly into the SMV) should be ligated if necessary. Vascular clamps are placed proximally and distally to the involved segment, which often includes the origin of the SV; the segment can then be excised. Systemic heparin is then administered, and an end-to-end vascular anastomosis is performed. If a graft is required, excellent conduits include the left renal vein and the internal jugular vein. There is no consensus on whether postoperative anticoagulation is needed following venous resection and reconstruction.

No studies have specifically investigated the association between a positive venous transection margin (either tangential or segmental) and survival. Therefore, intraoperative analysis of the vein margins is not advocated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree