Chapter 18 Disorders of Phagocyte Function

Clinical Approach to Patients With Disorders of Phagocyte Function

Index of Suspicion

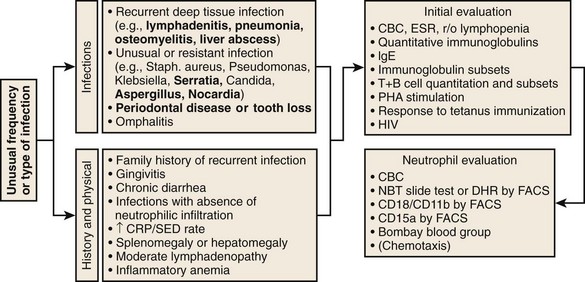

Specific features that may suggest a phagocytic defect are shown in Figure 18-2. Excellent discussions of this problem have been published (see Kyono and Coates1 and Dinauer and Newburger2). Four aspects of each patient’s infection history should be considered: frequency, severity, location, and responsible pathogen. Patients with unusual features in at least one of these aspects should alert the clinician to a possible underlying phagocyte disorder. When considering frequency, the patient’s age and associated medical conditions must be taken into account. For example, recurrent otitis media in a 2-year-old patient is far less worrisome than a similar history in a 40-year-old patient. The more unusual or severe the infections, the less frequently these have to occur before a phagocyte evaluation is indicated. Infections in unexpected anatomic locations, such as hepatic, pulmonary, and rectal abscesses, may indicate an underlying phagocyte defect. Childhood periodontal disease or gingivitis is distinctly uncommon, and in the absence of neutropenic conditions, strongly suggests underlying neutrophil dysfunction. The identification of certain pathogens (e.g., Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella spp., Aspergillus spp., Nocardia spp., Burkholderia cepacia, invasive candidiasis) in children and young adults can provide the strongest indications for pursuing further studies. A history of delayed separation of the umbilical cord is often mentioned as a sign of phagocytic defect. This is fairly common as an isolated finding and is usually of no significance. However, this is in conjunction with omphalitis or other pyogenic infections raises the possibility of LAD or chemotactic defects. A child with nystagmus, fair skin, and recurrent staphylococcal infections should be evaluated for CHS.

Evaluation

Performing a good history and physical examination to eliminate common causes of recurrent infection is important before looking for rare syndromes. For example, is the recurrent pneumonia caused by an aspirated foreign body in the bronchus? In general, patients should first be evaluated for lymphocyte or complement defects. A useful algorithm is presented in Figure 18-2. Note that testing described in this algorithm is not exhaustive, and patients with truly striking histories of unusual kinds of infections should be referred for further evaluation by specialized research laboratories.

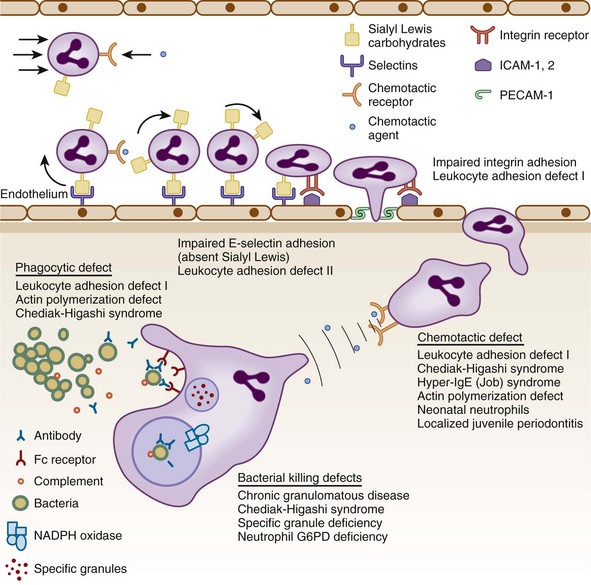

Figure 18-1 STEPS IN THE RESPONSE OF CIRCULATION NEUTROPHILS TO INFECTION.

(Modified from Kyoto W, Coates TD: A practical approach to neutrophil disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am 49:929, 2002, with permission.)

Diagnosis of Chronic Granulomatous Disease

NBT Slide Test

• No NBT reduction (absence of cells with dark blue formazan deposits) in both X-linked and AR forms of CGD (see Fig. 18-3, B).

• Usually no reduction in 50% of cells and normal in 50% for X-linked carrier. The percent positive cells can vary if there is unequal X inactivation and may appear normal or like CGD with extreme lyonization (see Fig. 18-3, C).

• False-positive results can occur (i.e., apparent failure to reduce NBT supporting the diagnosis of CGD) if the neutrophils do not adhere to the slide. This happens with greasy slides or with some cases of LAD. Using PMA to stimulate the cells will avoid this.

DHR Flow Cytometry

• This approach has replaced the NBT slide test in many laboratories. It has the advantage of assessing large numbers of cells and can give quantitation of the amount of oxidant production.

• The change in fluorescence channel number with stimulation is the critical number and not the percent positive cells.

• X-linked CGD patients will not respond at all and show no increase in fluorescence with stimulation (see Fig. 18-3, F).

• X-linked carriers will show about 50% of the cells that respond with a normal increase in fluorescence, and the other half will have no response. Degrees of unequal X inactivation are much more accurately quantified by this assay (see Fig. 18-3, G).

• AR patients, particularly those with absent p47phox, have some response to stimulation and show a small increase in fluorescence (see Fig. 18-3, H). This level of oxidant production is usually not visible on the NBT test.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree