The Ageing Pancreas

The pancreas has considerable functional reserve so that any anatomical changes associated with age have little, if any, effect on pancreatic function. Morphological changes, however, do occur as part of the ageing process. Ectasia of the main pancreatic duct occurs, which can cause confusion in the interpretation of the appearances on endoscopic pancreatography. Additionally, ductal epithelial hyperplasia and intralobular fibrosis, which rarely lead to pancreatic atrophy, can occur. In an autopsy study of the elderly in the UK, ductal narrowing not due to strictures, space-occupying lesions due to the superior mesenteric artery, splenic artery, aorta, vertebral osteophytes, sympathetic ganglia and lymph nodes were noted. The study also showed metastases in the pancreas, which could be mistaken for primary pancreatic tumours. Finally, ageing can be associated with impaired pancreatic blood supply due to atherosclerosis.

Functional studies have been carried out on elderly patients and compared with those on younger patients. The volume of pancreatic secretion falls in the elderly, as do the outputs of lipase, trypsin and phospholipase.1 There does not appear to be a corresponding fall in fat absorption. Changes are very variable in older persons, suggesting that disease processes such as arteriosclerosis and not ageing, per se, may be responsible for the small changes seen.

Inflammatory Diseases of the Pancreas

Acute Pancreatitis

Although alcohol abuse is the major cause of acute pancreatitis in the middle aged, it is less common as a cause in the elderly. Acute pancreatitis, however, occurs with increasing frequency in the elderly because of an increased prevalence of gallstones. A recent English study showed that hospital admission rates for acute pancreatitis had doubled over a 30 year period in all age groups but the case fatality rates had not altered.2 Hospital admissions for acute pancreatitis per 100 000 were 13 or more for both men and women over 65 years of age and the case fatality rates were 8 per 100 patients at 29 days after presentation and 7.4 at 30–364 days after presentation. Corresponding rates in the over-75 years old age group were even higher. In addition to alcohol and gallstones, other predisposing factors for acute pancreatitis in the elderly include hypercalcaemia (usually due to hyperparathyroidism), hypertriglyceridaemia and obstruction to pancreatic flow such as that caused by tumours, endoscopic pancreatography and uraemia. Acute pancreatitis occurs in up to 30% of patients following cardiac bypass surgery, perhaps because of the administration of large doses of intravenous calcium chloride. Acute pancreatitis is also associated with biliary sludge and cholecystectomy or endoscopic papillotomy may prevent recurrence. Elderly patients are more likely to be taking prescribed medication, but whether drugs are a major cause of acute pancreatitis is debatable. Most reports of drug-related pancreatitis are anecdotal and the potential severity of the disease precludes drug challenges. A large retrospective German study of acute pancreatitis implicated drugs as a possible cause in only 1.4% of the patients. The disease was mild and ran a benign course.3 It is now recognized that autoimmune pancreatitis is not rare in older persons.4 On imaging, it is characterized by pancreatic enlargement with an irregular narrow pancreatic duct. Histologically there is lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate with swirling fibrosis and obliterative phlebitis. The tissue stains positive for IgG4-positive cells. Serum levels of IgG4 are also elevated. It can be associated with biliary structures, retroperitoneal fibrosis, parotid infiltration and mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The condition is highly sensitive to steroid therapy.

Pathophysiology of Acute Pancreatitis

The basic underlying pathophysiological mechanism in acute pancreatitis is pancreatic duct obstruction. This allows autodigestion of the gland by its own enzymes. Reflux of bile and duodenal juices into the pancreatic duct are also important. In the majority of patients, the process is self-limiting but in some the disease becomes fulminating. This leads to pancreatic necrosis and activation of inflammatory cytokines, which can result in generalized organ failure (systemic inflammatory response syndrome). If the necrosed pancreas becomes infected by gut bacteria, the disease is often fatal.

Presentation of Acute Pancreatitis

The illness characteristically presents with severe abdominal pain, often leading to acute hospital admission. The pain usually occurs in the epigastrium and radiates through to the back and is often relieved by sitting forward. This presentation, however, may differ in the elderly when the illness may be confused with myocardial infarction or a perforated abdominal viscus.

The physical signs are those of an acute abdomen. Jaundice, vomiting, fever, tachycardia and hypotension may occur. If severe, haemorrhagic pancreatitis supervenes with retroperitoneal haemorrhage, which leads to bruising in the flanks (Grey Turner’s sign), around the umbilicus (Cullen’s sign) or even below the inguinal ligament (Fox’s sign).

Diagnosis of Acute Pancreatitis

The diagnosis is supported by the finding of high levels of amylase in the serum. Elevated levels of serum lipase are more specific than elevated amylase levels. The serum lipase rises within 4–8 h, peaks at 24 h and returns to normal in 8–14 days.

Radiological examinations are increasingly important and sophisticated. Straight abdominal X-rays may show a sentinel loop—an area of small bowel ileus adjacent to the inflamed pancreas. In severe pancreatitis, the chest X-ray can reveal a pleural effusion, areas of atelectasis and pulmonary oedema. These appearances occur in patients of all ages.

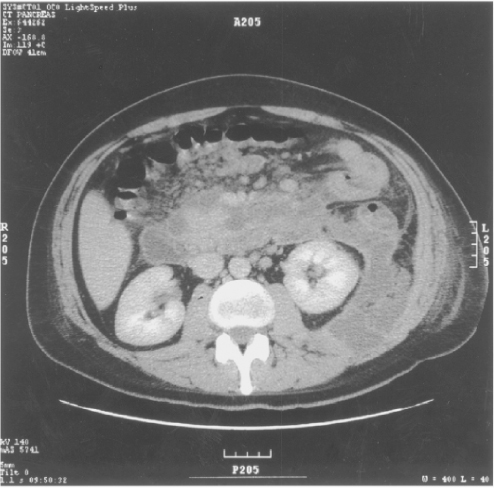

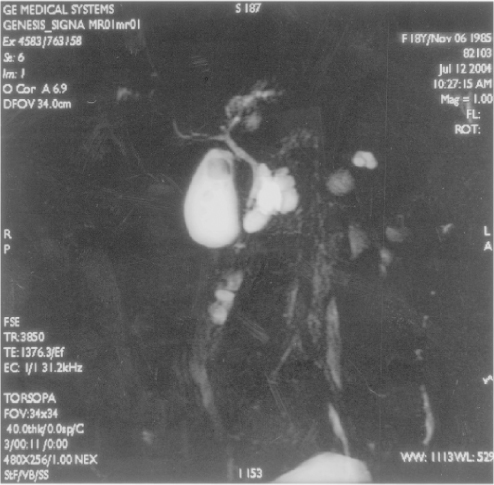

Ultrasonography is important. Gallstones and dilated bile ducts suggest pancreatitis of biliary origin. Overlying gas shadows often impair visualization of the pancreas, but when seen, the gland appears swollen. Ultrasonography is important in detecting pancreatic pseudocyst and fluid collections within the abdomen. Enhanced computed tomography (CT scanning) is useful in showing evidence of pancreatic necrosis and localized fluid collections both in and outside the pancreas (Figure 27.1). CT scanning may also reveal gallstones and bile duct or pancreatic duct dilatation not obvious in ultrasound scanning. In selected patients, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is useful in showing dilated bile ducts and gallbladder stones (Figure 27.2) and has the added advantage that bile duct stones can be cleared. When acute pancreatitis is diagnosed by these imaging methods, biochemical tests (serum levels of amylase and lipase) are elevated in over 90% of patients.

Assessment of the Severity of Acute Pancreatitis

In an individual patient, the severity of disease is judged by clinical observation. In an attempt to compare disease severity between centres, assess the results of therapeutic intervention and perhaps decide referral to specialized centres, various scoring systems have been introduced. One of the earlier scoring systems was introduced by Ranson et al.5 The index takes account of age, white blood cell counts, glucose levels, LDH and AST levels at admission and the decrease in haematocrit, elevation of the blood urea, decrease in serum calcium, pO2, base deficit and fluid balance at 48 h. Using similar measurements, modified ‘Glasgow criteria’ were later introduced.6 These prognostic indices are of proven value in predicting severe disease but suffer from the disadvantage that measurements are made over a period of 48 h. A score of >3 by either system indicates severe disease. The ‘APACHE II’ can be calculated on admission and is more sensitive and specific at 48 h after admission. The APACHE II grading system has the advantage that it can be measured from admission and throughout the hospital stay.7 Assessment of disease activity using CT scanning has also been studied and shown good correlation with local complications and mortality.8

Management of Acute Pancreatitis

Mild disease requires only observation and symptom control. Antibiotics are not routinely given. The 20–30% more ill patients need admission to an intensive care unit and careful monitoring. Nutrition is important and there is a debate as to whether the patient should be nourished by enteral routes or by parenteral routes. A meta-analysis suggested that enteral feeding was more appropriate. Compared with parenteral feeding, enteral feeding reduced the number of surgical interventions and the number of infections. Additionally, parenteral feeding is immunosuppressive and favours inflammation.9 The feeding tube should be placed in the jejunum to prevent pancreatic stimulation.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree