CHAPTER 10 Diet and the Gastrointestinal Tract

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• summarize the main features of digestion and absorption

• describe the most common chronic diseases which affect the intestinal tract, their epidemiology and clinical presentation, aetiology and pathophysiology

• discuss the role of diet in their management

• discuss current understanding of food allergies and intolerance

10.1 INTRODUCTION

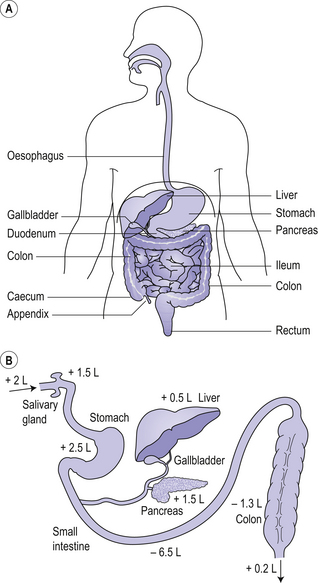

The primary function of the gastrointestinal tract is to facilitate digestion and the absorption of nutrients, although it also makes an important contribution to the body’s immune function. Intestinal function is modulated by gastrointestinal peptide hormones and an enteric nervous system (ENS). The GI tract comprises the mouth, pharynx, oesophagus, stomach, small intestine (duodenum, jejunum and ileum), the large bowel or colon, and the rectum and anus (Fig 10.1). Digestion is initiated in the mouth, continues in the stomach, and is completed in the small intestine. This process is aided by the presence of enzymes in saliva and gastric juices, and those secreted into the small intestine, as well as bile salts released by the gall bladder. Undigested material travels to the large bowel, where bacterial fermentation can occur, with the production of stool which is excreted via the rectum.

The immune system of the gastrointestinal tract has a number of different roles. Following ingestion of food or beverage the general trend is towards suppression of immunity to allow the digestion of substances foreign to the body, in other words, oral tolerance. However, active immunization may also follow the feeding of antigen and this is typically in the form of harmless secretory IgA antibody. In some circumstances there is, however, induction of potentially pathogenic immune reactions.

10.2 DIGESTION AND ABSORPTION

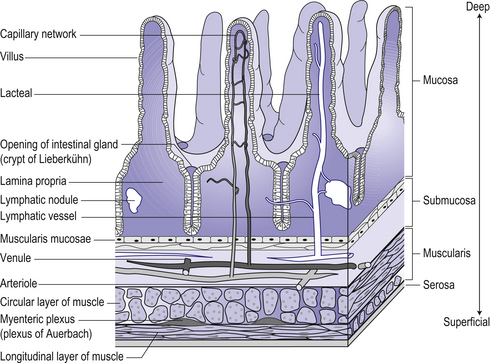

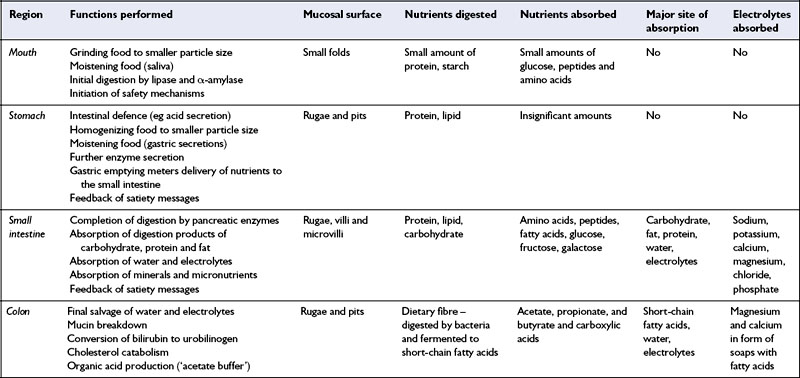

The gastrointestinal tract comprises different regions of activity in terms of digestion and absorption. Figure 10.2 depicts a diagrammatic representation of a cross-section across the intestinal wall, illustrating the relationship between the absorptive surface area and the blood and lacteal system that carry the products of digestion away from the gastrointestinal tract. The major components of the diet are starches, sugars, fats and proteins. These have to be hydrolysed to their constituent smaller molecules for absorption and metabolism. Starches and sugars are absorbed as monosaccharides; fats are absorbed as free fatty acids and glycerol (plus a small amount of intact triacylglycerol); proteins are absorbed as their constituent amino acids and small peptides. Table 10.1 summarizes the sites of nutrient absorption along the gastrointestinal tract.

Digestive and absorptive processes in the stomach

• the cephalic phase, during which the sight, aroma and anticipation of food stimulates the parasympathetic intestinal nervous system, leading to gastric acid and gastrin secretion

• the gastric phase, associated with increased acid and pepsinogen secretion

• the intestinal phase, which occurs towards the end of liquidization of food in the stomach.

Digestive and absorptive processes in the small intestine

Digestion and absorption of carbohydrate

In the small intestine carbohydrate digestion continues with the further hydrolysis of starch by pancreatic amylases to yield a mixture of glucose oligomers. These are further hydrolysed by the brush-border glucosidases to glucose, maltose and isomaltose. Disaccharides are hydrolysed to their constituent monosaccharides by disaccharidases on the brush border of the enterocytes. Uptake of glucose and galactose into the enterocytes takes place via the same active (sodium-linked) transporter (SGLT1), while fructose, some other monosaccharides and sugar alcohols are carried by passive transporters. Glucose can also be transported by a second glucose transporter, GLUT2, which responds to an increased dietary load of carbohydrate. Most carbohydrate absorption takes place in the duodenum, upper jejunum and proximal ileum.

Events in the colon

Water and electrolytes

The human small intestine absorbs 6.5 to 7.5 litres of water each day. Water absorption is proportional to the amount of substrate and electrolyte that moves across the membrane and the direction of water movement is governed by solute movement. In cholera, excessive secretion of chloride into the colon is accompanied by water secretion and diarrhoea, leading to dehydration and eventually death, unless treated.

10.3 DISEASES OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Food has a complex relationship with the integrity and function of the gastrointestinal tract. Dietary inadequacies can impair normal development, structure and function, leading to malabsorption and secondary nutrient deficiencies. The gastrointestinal tract can also be profoundly adversely affected by exposure to certain foods or nutrients, sometimes in association with a genetic susceptibility. Additionally, the use of appropriate dietary measures may be central to treatment of gastrointestinal disease. This part of the chapter will consider chronic gastrointestinal diseases and the role of diet in their aetiology and treatment.