CHAPTER 49 Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Illness

Introduction

The diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders among immigrants is very difficult and challenging. Refugees and immigrants often enter psychiatric treatment reluctantly and fearfully. Many have had severe traumatic experiences and suffer from PTSD and depression, but they may experience disorders along the full range of psychiatric syndromes. Rather than concentrating on stereotypes of behavior in a particular culture, it is better to treat patients as individuals who are interviewed with respect and patience. With patience and sensitivity a mutually agreed treatment plan usually can be formulated and should be spelled out, including the positive effect of medicine, the side effects, and the duration of treatment. Complications often involve the use of interpreters and misunderstanding the role of medications. The doctor–immigrant patient interaction is very complex and may involve somatic preoccupation, hidden psychological trauma, unconscious conversion reaction, physical pathology in addition to psychopathology, and outright deception. It takes time and sensitivity to establish trust in order to understand and treat these patients. A little gentle humor helps both doctor and patient cope (Box 49.1).

Epidemiological Data

There are enormous numbers of refugees, perhaps 21 million throughout the world.1 In addition, there are unknown numbers of people internally displaced in their own countries (such as in the United States with the recent hurricanes), and there are a number of people who come to the United States seeking asylum from the chaos and traumas of their own countries. In addition to legal migration there is immigration of undocumented people seeking economic advantages in a new country. The implication of this is that almost every physician will deal with immigrants and refugees of some type. There are now overwhelming data from European studies showing that immigrants, at least those coming from poor countries to the more developed countries of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Denmark, have a much higher rate of developing schizophrenia.2 Surprisingly, depression seems not to be higher in the first generation but may be higher in the second generation.3,4

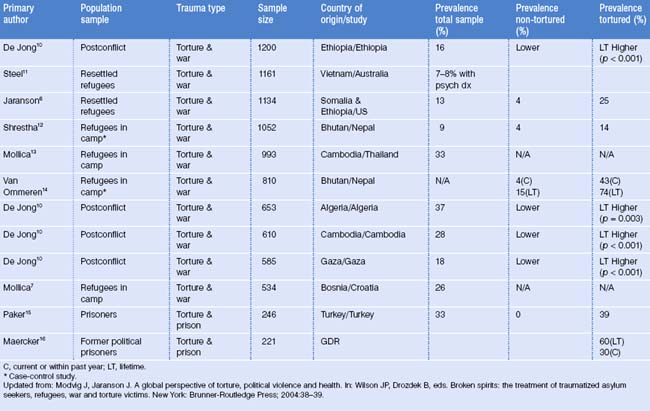

On the other hand, most refugees who have fled war-torn areas have a very high rate of psychiatric disorders. Prevalence rates have shown that up to 50% of Cambodians have had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) plus depression.5 A high percentage has also been found among Somali6 and Bosnian refugees.7 Perhaps the most vulnerable group has been immigrant school children who have a high exposure to violence. PTSD symptoms in the clinical range of 32% and depression of 16% have been found.8 These studies indicate high levels of psychiatric disturbances, particularly PTSD and major depressive disorder, among immigrants, especially refugees. Much more psychological distress has been found among asylum seekers whose legal status and ability to stay in the country are often undermined. Living in limbo, they experience additional anxiety.9 Prevalence rates of post-traumatic stress among traumatized populations are shown in Table 49.1.

Diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Although many reactions to severe stress have been recorded throughout history and more recently in the American Civil War and World War I, PTSD was officially introduced as a diagnostic category into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition (DSM-III), of the American Psychiatric Association in 1980.17 Modest modifications have occurred in subsequent revisions of DSM-IV.18

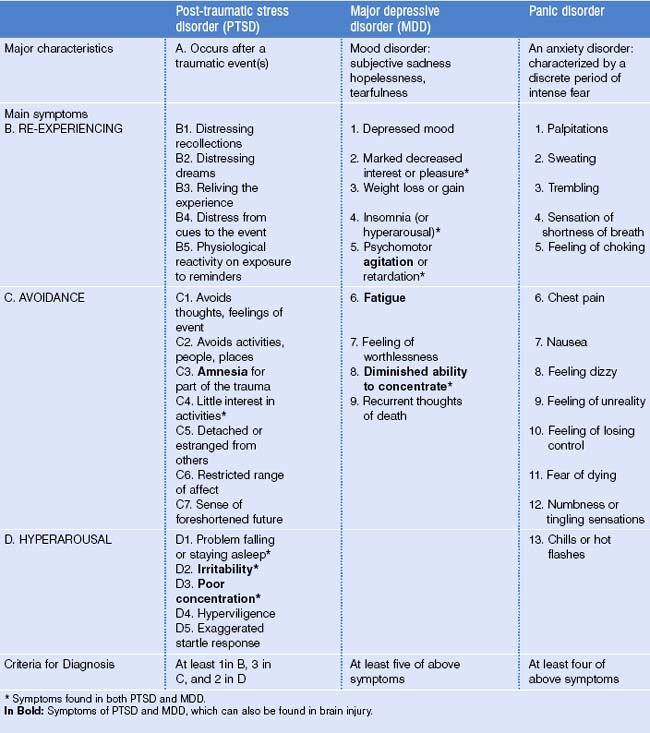

ICD-1019 and DSM-IV differ in their criteria to define PTSD. In DSM-IV, PTSD lasts more than a month and causes ‘clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.’18 (See p. 429 of cited reference.) PTSD can be specified as acute if symptoms last fewer than 3 months, chronic if duration is 3 months or more, or with delayed onset if symptoms begin after 6 months or longer. Symptoms are grouped into categories or criteria of reexperiencing, avoidance, and hypervigilence and listed in Table 49.2. ICD-10 has two relevant diagnostic categories: (1) ‘Post-traumatic stress disorder’ (F43.1), which occurs within 6 months of the traumatic event, and (2) ‘Enduring personality change after catastrophic experience’ (F62.0), which must have been present for at least 2 years. Diagnostic guidelines state that this personality change causes significant interference with daily personal functioning, represents inflexible and maladaptive features, and cannot be attributed to a preexistent personality disorder or to a mental disorder other than PTSD.

From a clinical perspective, the diagnostic category of PTSD is meaningful, and an argument emphasizing the universal aspects of PTSD relates to the many recent research findings on the biological aspects of PTSD.20 Cross-cultural evidence indicates that PTSD is a useful concept and diagnostic entity that transcends culture. Similar symptoms have been found among Cambodian adolescent refugees,21 Mexican hurricane survivors,22 and Kalahari Bushmen.23 Although some have warned about the dangers of applying Western concepts of trauma to refugees,24 from both a practical and a heuristic viewpoint, PTSD represents common responses of humans to massive trauma.25

PTSD is highly comorbid with depression, occurring together over 80% of the time after trauma (personal data, Intercultural Psychiatric Program). Indeed, depression can occur long after traumatic events. Panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are also common comorbid disorders with PTSD. Comorbidity with other anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder, is also common. Table 49.2 compares PTSD, major depression (MDD) and panic disorder, which are among the most frequently diagnosed psychiatric illnesses in immigrants and refugees. The symptoms of PTSD and MDD that are common between the two diagnoses are asterisked in this table.

Unlike American veterans, where alcohol and drug abuse are very common and related to PTSD, alcohol abuse is forbidden in Muslim and Buddhist cultures and may account for its lower prevalence. The prevalence rate is higher among traumatized Hispanic refugees from Central America,26 where alcohol abuse is a problem.

Psychosis and organicity

Europeans have found higher rates of schizophrenia in immigrants, rates that have been much higher and cannot be explained by immigrant stress or diagnostic problems related to culture or even racism.27 We have also found high rates of psychosis among Somalis, which may be related to cultural stress as much as to the use of Khat, an amphetamine-like stimulant known to cause psychotic symptoms. It is sometimes difficult to separate intrusive thought from hallucination, but questioning whether it is a memory or coming from an external source can provide clues. A family member seeing a change in personality provides perhaps the best evidence.

Perhaps it is a disservice to some patients to say that they have a normal reaction to abnormal circumstances, a current approach fashionable in the trauma field. In fact, some patients have a major psychiatric disorder such as schizophrenia or a neurological disorder such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) (http://www.neuroskills.com/tbi/mtbi.shtml), or organic brain syndrome (OBS). Starvation and chronic malnutrition in refugees and immigrants can also cause significant brain damage, not always irreversible.

Although psychological sequelae might be the most important consequences for the majority of survivors, TBI might be more common than one would expect. Many patients have had multiple head traumas from beatings, shrapnel wounds during war, or falls and accidents during chaotic escapes.28 Symptoms including poor concentration, loss of recent memory, irritability, and lack of energy can be found in PTSD, depression, and TBI, making the differential complicated. These symptoms are identified in bold type in Table 49.2, indicating how much overlap occurs in the differential with functional disorders such as PTSD and MDD. TBI must be diagnosed to avoid inadequate treatment, but diagnosis can be difficult if there are no neurological soft signs, positive X-ray, MRI or EEG findings. Neuropsychological testing might also be of limited value in refugees and immigrants, but few alternatives exist. We routinely ask about loss of consciousness lasting more than 3 minutes and any symptoms that the patient may relate to this. The patient might also suffer from both PTSD and TBI, limiting the success of treatment.

Recommended Knowledge/Required Reading Prior to Seeing the Patient

Physicians should have an overall knowledge of some of the issues involved in the patient populations that they are treating in order to ask sensitive and informed questions about past experiences. For example, clinicians who treat refugees need to know about the Vietnam War, in which hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese left after the fall of Saigon in 1979; the 4 years of the Pol Pot experience in Cambodia, 1975–1979; almost a decade of civil wars in Central America, particularly Guatemala and El Salvador in the 1980s; the Somali wars and the Bosnian wars in 1991–1993; and the Afghani wars under the Taliban ending in 2001. These experiences often include civil unrest, random violence, and forced separation from family members, starvation, witnessing death of friends and family, and refugee status in a second country before finally coming to the United States. In addition, many have suffered torture for reasons including political vengeance or ethnic hostility. Realizing this allows clinicians to consider possible traumas and related diagnoses.

Interviewing Approaches

It is not unusual for the patient to present physical complaints as the first symptoms and, as the case in Box 1 demonstrated, to be reluctant to go beyond that. Psychiatric rating scales are usually not very helpful for immigrants,29 but another argument is offered in the Screening chapter by Eisenman. Most immigrants from severely traumatized areas do not speak English. Many are illiterate in their own languages and have no familiarity with the Likert scales often used as diagnostic tools. Furthermore, if the questions are read to them through a counselor or interpreter, the relationship may affect the answers, e.g. a woman won’t tell a male counselor about loss of libido. Indeed, some issues are so sensitive that immigrants may never discuss them even after years of treatment; rape and genital mutilation are two such issues that are very difficult for patients to discuss. In the authors’ opinion, the primary diagnosis is made through careful, sensitive, and often lengthy interviewing. Specific cultural approaches (e.g. how to interview Vietnamese, how to treat Somalis) are not as important as the general approach. Refugees often are sensitive to rejection. Impatience, rapid questioning, and expecting quick answers often lead to inaccurate responses and merely increase the level of pressure during the interview. It is very important for the clinician to patiently listen and to encourage the interpreter to do the same. Many times the authors have had to stop an interview and ask the interpreter to be more sensitive or to slow down.

Another primary issue is awareness of the nonverbal communication of the patient. Often, the answer and the nonverbal expression do not match. For example, an interpreter may give a patient’s response as, ‘I have no problems,’ while the patient has a sad look, psychomotor retardation, and long latencies in responding. We have found that it is useful to take the physical symptoms of the patient seriously as a starting point, e.g. ‘How long have your headaches lasted, what have you done for them, has anything made them better or worse?’ This is a non-threatening approach with which the patient can identify. It is probably not useful to ask about psychosocial stressors immediately, but rather to ask about physical symptoms which may indicate major psychiatric disorders. For PTSD, asking about nightmares, irritability, intrusive thoughts, and avoidance behavior, such as avoiding TV shows of violence or war scenes, can be very useful. These are relatively straightforward and non-threatening questions. For depression, asking about poor sleep, poor appetite, fatigue, and poor concentration rather than the more subjective symptoms of helplessness, hopelessness, negative view of the future, etc. is also less threatening and more universally accepted. When one finds that there are a number of symptoms related to PTSD and/or depression, follow-up can lead to some of the psychosocial events in the patient’s life. For example, an affirmative response to nightmares could be followed up by asking whether these nightmares are about real events that happened to the patient in Bosnia (Somali, Cambodia, etc.). Then one can ask, ‘Can you tell me more about other things that have happened to you?’ Often, the patients will provide additional information but will terminate the process by saying, ‘I don’t want to talk about it anymore,’ or, ‘I don’t want to be reminded of it.’ Avoidance behavior has been a necessary defense mechanism for many refugees. This should be respected and the clinician may simply say, ‘I understand that what happened to you in the past is very severe,’ and then make an interpretation that most patients have been able to understand, e.g. ‘You went through very, very difficult events in the past and now your body and your mind are still reacting to those events, giving you many of the symptoms you have now.’ One can list those symptoms such as nightmares, poor sleep, or poor concentration. This connection of psychosocial events with current symptoms has often been helpful for patients. Sometimes, in their chaotic situation of immigrant status and adjustment to a new country, they have not connected the past and the present problems. Additionally, it is useful to ask about ongoing current problems faced by many immigrants. These include language, financial, and housing problems, and concern about the education and socialization of their children, i.e. are they becoming too Americanized?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree