DIAGNOSIS

With a systematic approach, the clinician will often find an etiology for delayed puberty. The initial history and physical examination form the foundation of the investigation, and particular emphasis is given to the medical history, previous growth charts, and growth velocity over the previous 4 to 6 months. A thorough review of systems must be undertaken; questioning for symptoms of chronic disease and asking about the sense of smell are important. A review of the family history is vital and may support a diagnosis of constitutional delay if positive for similar pubertal delay. In addition, parental heights and the calculated target height are important components of the investigation. The physical examination must incorporate accurate anthropometric measurements (weight, height obtained with a stadiometer, upper/lower segment ratio, arm span) and Tanner staging. The presence of pubic hair does not reassure the clinician that puberty has been attained, since adrenarche alone could explain this milestone. Finally, one should search for stigmata of the various congenital syndromes associated with delayed puberty as well as for subtle evidence of chronic disease.

As most children with delayed puberty will represent variants of normal (i.e., constitutional delay), an involved costly investigation is not initially warranted. Instead, continued observation with accurate growth velocity assessment and well-documented physical examinations may be sufficient.However, if there are features of the presenting history or examination that indicate an underlying pathologic diagnosis, if growth velocity is much less than expected for bone age, or if further growth and development do not occur as anticipated, it is necessary to pursue a more complete evaluation.

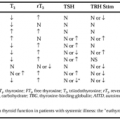

Reasonable screening tests include a complete blood cell count and sedimentation rate, basic chemistry profile, urinalysis,

and thyroid function tests. IGF-I and insulin-like growth factor–binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) levels should be considered if there is short stature or subnormal growth velocity, keeping in mind that these values are often low for chronologic age (although appropriate for bone age) in children with constitutional delay.109 A bone age provides invaluable information, specifically in regard to the potential for continued growth. A karyotype should be considered in all girls (even in those without obvious stigmata of Turner syndrome) and in those boys with elevated gonadotropins or phenotypic features suggestive of a chromosomal disorder. MRI of the brain and sella turcica should be obtained in those individuals suspected of having permanent hypogonadotropic hypogonadism as well as those patients with visual field cuts or symptoms suggestive of an intracranial mass. Children with late onset of subnormal growth velocity or posterior pituitary insufficiency would also warrant CNS imaging.

and thyroid function tests. IGF-I and insulin-like growth factor–binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) levels should be considered if there is short stature or subnormal growth velocity, keeping in mind that these values are often low for chronologic age (although appropriate for bone age) in children with constitutional delay.109 A bone age provides invaluable information, specifically in regard to the potential for continued growth. A karyotype should be considered in all girls (even in those without obvious stigmata of Turner syndrome) and in those boys with elevated gonadotropins or phenotypic features suggestive of a chromosomal disorder. MRI of the brain and sella turcica should be obtained in those individuals suspected of having permanent hypogonadotropic hypogonadism as well as those patients with visual field cuts or symptoms suggestive of an intracranial mass. Children with late onset of subnormal growth velocity or posterior pituitary insufficiency would also warrant CNS imaging.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree