Key points

- An holistic proactive and integrated approach is needed to achieve effective diabetes management, manage age-, and diabetes-related health risks and ensure management strategies are appropriate for the individual.

- Increasing age is associated with insulin resistance that predisposes older people to diabetes and diabetes is common in people over 65. Most have Type 2 diabetes but Type 1 and LADA also occur.

- The onset of diabetes is often insidious in older people with non-specific symptoms that can be mistaken for advancing age or other conditions.

- Long-term complications are often present at diagnosis.

- The individual should be encouraged to maintain independent, self-care within their capabilities for as long as possible but carer assistance is often needed especially during illnesses.

- There is limited evidence for metabolic targets in older people. Targets must be appropriate to the individual and limit the risk of adverse events such as hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia, and falls.

Rationale

Older people with diabetes are not a heterogeneous group. Some are healthy and active; others are frail and have multiple health problems. Managing diabetes in older people is complex and is an increasingly important aspect of nursing care as the population ages and the incidence and prevalence of diabetes increases with increasing age. Diabetes manifests differently in older people and their healthcare needs are different. Likewise, diabetes is likely to adversely affect many activities of daily living including, socialising and driving as well as physical and mental functioning all of which affect self-care ability.

Introduction

The ageing process is a progressive deterioration of bodily functions over the lifespan (US National Institute of Health (NIH) undated) whose characteristics are destructive, progressive, intrinsically determined and universal. Ageing occurs at different rates among individuals and among individual organs and tissues in the body. There are many theories but no consensus about what causes ageing. The two major schools of thought are: (1) Ageing is programmed and (2) Ageing is random, each accompanied by specific theories, see Table 12.1. These theories give rise to the question: Can ageing be cured (anti-ageing research) or should it be managed better to maintain wellness and a short decline to death because it is a natural process? Strategies to maintain wellness include:

- Reducing risk factors such as smoking, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes.

- Improving micronutrient deficiencies and using antioxidant supplements based on the Ames hypothesis that an adaptive triage process occurs in the body when micronutrients are scarce that favours short-term survival over long-term health-energy pathways are favoured over DNA repair (Ames 2006).

- Anti-ageing strategies such as:

- diets, calorie restriction, and the Okinawa diet, mushrooms

- anti-ageing nutrient supplements to reduce inflammation and oxidative stress such as SOD, CQ-10, Gingko, Ginseng, Brahmi

- hormones such as melatonin

- medicines to improve insulin sensitivity, vasodilators, and mind stimulants.

- diets, calorie restriction, and the Okinawa diet, mushrooms

- Under research: gene therapy, therapeutic cloning, cell therapy, nanotechnology (Grossman 2005).

Advancing age is associated with glucose intolerance, changes in renal function, which alters medicine pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, reduced sense of smell, hearing, sight, mobility, reduced muscle mass, and changed cognitive functioning, all of which increase the individual’s vulnerability to ill health. Significantly, chronological age is not the most important factor to consider when deciding management options. The functional status and biological age are more important determinants of care (National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) 1994). Particular problems encountered in older people are shown in Table 12.2. It is important to realise that older people in hospital or living in residential aged care facilities do not represent the majority of older individuals living in the community (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) 2002).

The Victorian Department of Human Services (DHS) (2003) identified several specific care issues needed to maintain functional status:

Table 12.1 Theories of ageing. Currently there is no general agreement about the causes of ageing but most experts favour cellular damage theories. These seem to apply to uncontrolled diabetes where similar theories have been proposed for the development of diabetes complications. See Chapter 8.

| Programmed theories Ageing is a designed process (built in obsolescence) | Damage theories Ageing is due to accumulated molecular damage especially to DNA and proteins that causes cell, organ, and system dysfunction |

| Disposable soma Organisms exist to reproduce and then die | Systematic damage theories: Immune system failure Failure of neuroendocrine regulation Failure to adapt |

| Antagonistic pleiotropy Genes that are essential and advantageous in young people cause damage in older people Developmental programming Ageing is regulated by genes and damage only begins to occur after development is complete Neuroendocrine programming Biological clock regulated by the hypothalamus. Hormone production eventually diminishes and causes changes associated with ageing Rate of living (live fast die young) Every person has a fixed metabolic potential that can be affected by lifestyle also known as metabolic burnout Genetic programming Ageing is preprogrammed in genes that might affect germ cell function, cell division, and cell death | Cellular damage theories caused by free radical damage by reactive oxygen species (ROS), hyperglycaemia causing advanced glycated end products (AGE) and binding of AGE receptors (RAGE) to AGE resulting in oxidative and inflammatory effects (accelerated in diabetes), and/or chronic inflammation caused by inflammatory cytokines and eicosanoids, which with infection can induce oxidant-generating enzymes such as NADPH oxidase and nitric oxide synthase that produce ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) that react with each other to form more potent reactive species that damage DNA and contribute to diseases such as cancer by activating oncogenes and/or suppressing tumour suppressor proteins. Damage to cell membranes Somatic mutations Failure of repair processes |

DHS (2003) also noted the need to ensure relevant services are available and that they function optimally and to consider the health and well being of carers. The NHMRC series on clinical care of older people (number 3 1994) focuses on reducing hospital admissions and preventing complications in hospital encompasses most of these issues and highlights the need for multidisciplinary health professional care. In particular, The NHMRC emphasised the atypical presentation of many illnesses in older people.

Table 12.2 Particular problems encountered in the elderly person with diabetes and the resultant risks associated with the problem. Many of these conditions affect activities of daily living and extended activities of daily living. They represent a cumulative health burden and almost all represent a falls risk and contribute to the risk of driving accidents.

| Problem | Associated risk |

| Hyperglycaemia leading to: | Constipation |

| Postural hypotension | |

| Dehydration and electrolyte imbalance | |

| Polyuria and nocturia, which may present as urinary incontinence | |

| Hyperosmolar coma and ketoacidosis | |

| Impaired cognition | |

| Thrombosis | |

| Infection, for example, UTI | |

| Impaired wound healing | |

| Postural hypotension | |

| Decreased pain threshold | |

| Exacerbated neuropathic pain | |

| Lowered mood, lethargy, compromised self-care | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Falls | |

| Chewing problems and swallowing difficulties | Hypoglycaemia |

| Nutritional deficiencies: | |

| • Impaired immune response | |

| • Infection risk | |

| • Decreased plasma protein | |

| Impaired wound healing: | |

| • Higher fat intake | |

| • Dehydration | |

| • Muscle wasting and reduced strength in the lower limbs, which affect ADLs | |

| • increased risk of systemic diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular diseases | |

| • Driving deficits | |

| • Difficulty swallowing medicines Energy deficits | |

| Increased morbidity and mortality | |

| Falls | |

| Cerebral insufficiency | Stroke |

| Non-recognition of hypoglycaemia | |

| Trauma | |

| Impaired cognition | |

| TIAs being confused with hypoglycaemia | |

| Increased prevalence of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias | |

| Falls | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Cardiac insufficiency | Myocardial infarction |

| Confusion | |

| Poor wound healing | |

| Poor peripheral circulation | |

| Foot ulcers | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Falls | |

| Autonomic neuropathy | Postural hypotension |

| Gustatory sweating | |

| Urinary tract infections and incontinence | |

| Unrecognised hypoglycaemia | |

| Silent myocardial infarction | |

| Decreased/delayed food absorption | |

| Poor nutrition | |

| Infections, pain | |

| Decreased motor skills | |

| Erectile dysfunction | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Falls | |

| Peripheral insufficiency | Trauma |

| Foot/leg ulcers | |

| Claudication | |

| Falls | |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Unstable gait |

| Foot ulcers | |

| Depression | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Falls | |

| Other neuropathies such as Bell’s palsy | Reduced self-care |

| Loss of independence | |

| Body image changes | |

| Visual impairment Changed colour perception (blue, green, violet) | Self-care deficits |

| Depression | |

| Loss of independence | |

| Social isolation | |

| Education difficulties with types of materials used and, differentiating medications | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Skin atrophy | Pressure ulcers, skin tears |

| Infection | |

| Progression of acute wounds to chronic wounds | |

| Stress and depression | |

| Oedema | |

| Communication problems | Misunderstanding |

| Confusion | |

| Inaccurate self-care | |

| Stress | |

| Social isolation | |

| Stress and depression | Inadequate self-care |

| Hypertension | |

| Hyperglycaemia | |

| Hypoglycaemia | |

| Impacts on wound healing | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Suicide risk | |

| Falls | |

| Renal disease associated with diabetes and as a normal part of ageing | Decreased medicine clearance and prolonged activity End-stage renal disease requiring dialysis |

| Difficulty interpreting investigative blood tests | |

| Malnutrition | |

| Reduced choice of OHA | |

| Dehydration | |

| Hyperosmolar coma | |

| Lactic acidosis | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Falls | |

| Failure to recognise thirst (normal ageing process) | Dehydration |

| Hyperglycaemia | |

| Confusion | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Falls | |

| Cognitive impairment | Self-care deficits |

| Education difficulties | |

| Reduced quality of life | |

| Falls | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Musculoskeletal disorders such as Dupytren’s contracture,cherioarthropathy, flexor tenosynovitis, carpel tunnel syndrom | Difficulty performing activities of daily living |

| Pain and discomfort | |

| Driving deficits | |

| Falls |

Many illnesses present with atypical symptoms, which can delay appropriate diagnosis and management and result in significant morbidity or death such as:

- Failure to thrive.

- Immobility.

- Postural instability.

- Incontinence.

- Confusion.

- Depression.

- Fatigue and lethargy.

- Weight loss.

- Undetected hyperglycaemia (IGT) can be present in non-diabetic older people and diabetes triggered by an intercurrent illness, a diabetes complication or emotional stress, and present as:

- constipation

- dehydration

- postural hypotension

- confusion

- polyuria or urinary incontinence

- infections such as UTI and URTI.

- constipation

In addition, older people with diabetes usually have multiple health problems, some of which are the result of diabetes-related complications and are present at diagnosis in >20% of people (NHMRC 1992). Thus, actively screening older people in hospital and care facilities is warranted. Bayliss et al. (2007) found an average of 8.7 chronic diseases present per person in a cross-sectional survey of people aged >65 years. Compared with newly diagnosed non-diabetics, older people have a 9% mortality rate, 40% more lower leg complications (claudication, cellulitis), double the risk of cardiovascular disease including heart failure, double the risk of end-stage renal disease, and are 60% more likely to have vision problems (Bethel et al. 2007). They are also at great risk of falling, especially in hospital.

Managing diabetes, its complications, and other comorbid diseases requires multiple medicines, and often several doses per medicine per day. Many commonly used laboratory tests have lower specificity and sensitivity in older people, which can further complicate the clinical picture. For example, serum creatinine may not detect renal impairment especially in normal or underweight individuals (Gianelli et al. (2007) and contraindicated medicines may not be stopped.

Interestingly, despite the association among obesity and morbidity and mortality (Hu et al. 2005; Chen et al. 2006) being overweight is associated with longer life expectancy in men and women >80 years and underweight with shorter life expectancy even when other comorbidities are present (Takata et al. 2007). Weight loss is associated with total mortality in older people independently of low body weight (Keller et al. 2004). These findings suggest recommending older overweight people lose weight may actually put them at risk. Likewise, HbAlc <7% increases the risk of hypoglycaemia and its consequences. HbAlc >10% has immediate physiological effects as well as effects on neutrophil function and wound healing (Shekelle & Vijan 2007).

Evidence for ideal HbAlc targets in older people is limited, apart from the UKPDS, which focused on preventing long-term complications rather than safety and maximising functioning. The Australian Diabetes Educators Association (ADEA) (2003) proposed targets based on a systematic review, but they are not intended for older people in aged care facilities. Brown et al. (2003) recommended HbAlc <7% for most older people; and <8% in frail older people because preventing the short-term consequences of hypo and hyperglycaemia and their associated symptoms and risks to safety and quality of life, might be more important than preventing long-term complications. Management also depends on the individual’s functional status.

Determining functional status

Older people in hospital and care facilities are a vulnerable group and the latter often receive suboptimal care (Kirkland 2000). Sinclair et al. (1997) found 40% of residents in elderly care facilities were on long-acting sulphonylureas, fewer than 1 in 10 had any regular diabetes follow-up, they had more hospital admissions than people without diabetes, stayed in hospital longer and had more complications. In addition, staff and resident knowledge about diabetes was deficient. Likewise, functional decline occurs in 30–50% of older people during hospitalisation and ∼30% >70 years return home with ADL deficits (Royal Melbourne Hospital 2002). Functional decline is associated with long duration of hospitalisation and manifests gradually as malnutrition, reduced mobility, compromised skin integrity, incontinence, falls, delirium, depression, and inadequate self-care.

The degree of disability is likely to change over time, sometimes rapidly, and during illness, and affect the amount of assistance the individual needs, either on a temporary basis or in the longer term. Changing circumstances often have financial implications for the individual and the health system. Table 12.3 suggests some key questions that can help decide the level of assistance needed and appropriate management. In addition, geomaps and ecomaps can provide a great deal of information about the individual’s social network and relationships, see Chapter 2. Annual diabetes complication screening should encompass screening for depression, comorbidities, falls risk, incontinence, pain and memory deficits, degree of frailty, functional status including driving ability, and a structured medicines review. The current Australian ANDIAB review does not encompass these issues and needs to be used in conjunction with other screening tools for older people.

Many of these activities depend on the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL). There are two main types of ADL: physical (PADL) that encompasses essential daily activities such as bathing and dressing; and instrumental (IADL), which enable the individual to live independently in society and are more complex (Kock & Garratt 2001). IADL assessment must be based on activities relevant to the individual and take account of their physical surroundings, culture, and interests. For example, assessing an older person when they are in hospital and their blood glucose levels are in the optimal range may not accurately reflect their ADL and adverse event risk level at home (Dunning & Alford 1993).

Determining the frailty level (frailty index FI) might help identify older people likely to suffer adverse health effects (Kulminski et al. 2007). Frailty is a consequence of declining physical reserve and altered functioning in multiple physiological systems, which make the individual vulnerable to physical and mental stressors (Bortz 2002; Fried et al. 2004). Several definitions of frailty exist including the following:

The frailty state can be described using a cumulative index of health and well being deficiencies that is assessable for each individual … the fraction of deficits in a list of items that measure health and well being [constitutes the frailty index (FI)]

(Kulminski et al. 2007)

A number of methods of estimating the FI has been proposed. The most useful enable clinicians to use health information already being collected to predict those at risk of adverse health outcomes. Frailty could be calculated for older people with diabetes as part of the annual complication screening process and be monitored proactively and prospectively.

Table 12.3 Key issues that need to be considered when assessing disability in older people with diabetes. Repeat measures may be needed especially during acute illnesses when the physical and mental condition can change rapidly. These issues should be considered as part of the standard diabetes complication screening process. Reproduced with permission from Dunning, T. (2006) Managing Diabetes in Older People. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford.

| Questions | Implications |

| (1) What activities are limited and to what degree? | A precise description of the disability is important in order to plan appropriate medical and nursing care and evaluate outcomes. |

| (2) Which disease processes are causing the disability? | Attributing disability to ‘old age’ is not an appropriate diagnosis. Common causes of disability include arthritis, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, stroke and visual impairment. One or more of these comorbidities often coexist with diabetes. Polypharmacy is likely. In some cases the medicine of choice for some comorbidities increases blood glucose levels. |

| (3) What is the person’s mental state? Various assessment tools are used to assess mental status, for example the MiniMental, however their limitations need to be considered. | Evidence of memory loss, disorientation, confused behaviour and personality change may indicate diseases of the brain, dementia states or metabolic changes such as high or low blood glucose levels that impair mental processing. Consideration should also be given to the presence of anxiety, depression and the individual’s general mental approach to life (positive or pessimistic) and hearing deficits. |

| (4) What is the person’s social situation? See Figure 2.1 | Disability implies dependence on others. It is important to identify the services and people likely to be able to support the individual if they do require help. In addition, it is important to ensure the person who takes on the care is supported and their personal health and wellbeing considered to prevent stress, sleep disturbance and ill health in the carer, especially if they are also elderly. |

Cognitive impairment

Cognitive decline in older people with diabetes is multifactorial due to advancing age and vascular dementia but not other forms of dementia (Allen et al. 2004), hyperglycaemia (Morley & Flood 1990), and hypoglycaemia, and increasing duration of diabetes. Large community studies suggest older people with diabetes have worse cognitive functioning than non-diabetics (Croxon et al. 1995; Gregg et al. 2000; Logroscino et al. 2004), and the decline is more rapid in those with diabetes (Biessels et al. 2002). The Framingham Study suggests hypertension and diabetes are independent risk factors for poor performance on memory and visual organisation tests (Elias et al. 1997). In contrast, Asiakopoulou et al. (2002) demonstrated minimal effects on verbal and logical memory when blood glucose control is optimal.

In acute illness it is important to differentiate cognitive decline from hypoglycaemia, hyperglycaemia, and hyperosmolar states, delirium, MI, and other causes. Delirium is associated with:

- Prolonged hospitalisation, poor outcomes and admission to aged care facilities.

- Functional decline.

- Increased use of chemical and other restraints that increase the falls risk.

- Presence of infection, which can precipitate hyperosmolar states.

- Multiple comorbidities.

- Severe illness.

- Dehydration, which can precipitate hyperosmolar states and may lead to a diagnosis of diabetes in undiagnosed at risk individuals, see chapter 7.

- Alcohol abuse.

- Falls and fractures.

- Psychotropic medications.

Delirium, but not the severity, can be distinguished from non-reversible cognitive impairment using the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) (Waszynski 2004). The CAM has concurrent validity with the MMSE but has not been tested in clinical settings and is associated with a 10% false-positive rate. The key aspects of the CAM are shown in the following list. A diagnosis of delirium is made if 1 and 2 and either 3 or 4 are present:

Fluid balance disturbances are common in older people largely as a result of changes in body water composition, declining renal function, and reduced thirst perception (Davies et al. 1995). Dehydration is common in community dwelling older people (Warren et al. 1996) occurring in ∼6.7% of those >65 years in hospital and is the principal diagnosis in 1.4% (Warren et al. 1994). Dehydration is present in 50% of residents in aged care facilities with a febrile illness who are often referred to hospital due to dehydration (Bourdel-Marchasson et al. 2004). Dehydration should be preventable in hospital and aged care facilities. Management guidelines should encompass strategies to do so considering the following information.

Dehydration is associated with hyperglycaemia and DKA and HONK (see Chapter 7), thromboembolism, infections, renal calculi, falls and constipation, and causes up to 50% mortality if it is not adequately managed (Wilson et al. 2003), and poor mental functioning (Wilson et al. 2003; Faes et al. 2007). Early diagnosis is difficult because of the atypical presentation in older people and because there is no absolute definition of dehydration (Weinberg et al. 1995). A commonly used definition is:

‘… a clinically relevant decrease of an individual’s optimal Total Body water (TBW) amount and may occur with or without loss of electrolytes’.

(Faes et al. 2007)

Thus, the degree of dehydration depends on the relative rather than the actual total intracellular and extracellular water loss. People with low body weight show signs of dehydration after losing small amounts of water. Significantly, ∼25% of older people drink < 1 litre of fluid per day, especially those over 85 (Volkert et al. 2004). Risk factors for dehydration include:

- age over 85 years

- female

- having ≥chronic diseases

- using ≥5 medicines

- medicine-related factors such as high protein oral or enteral feeds, laxatives, antidepressants, and diuretics

- fasting for surgery or investigative procedures

- fluid loss such as diarrhoea, vomiting, hyperglycaemia

- being confined to bed/chair

- poor mobility including manual dexterity

- poor eye-hand coordiantion

- communication difficulties

- inability to feed themselves

- social isolation

- hot weather

- having Alzheimer’s disease and other cognitive disturbances (Lavizzo-Mourey et al.1988).

The diagnosis is made on clinical signs such as recent weight loss >3% body weight, presence of an intercurrent illness, dry mucous membranes, coated tongue, sunken eyes, confusion, hypotension, muscle weakness in the upper body, and falls. Laboratory investigations such as serum osmolality, creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), BUN/ creatinine ratio, and electrolytes as well as urine pH and output are useful. Three forms of dehydration occur:

• Hypertonic: sodium >150mmol/L or serum osmolality >300 mosmol/L.

• Isotonic dehydration occurs when water and electrolyte loss are balanced, for example, diarrhoea and vomiting.

• Hypotonic dehydration results when electrolyte loss is greater than water loss, for example, overuse of diuretics.

The prevalence of the isotonic and hypotonic dehydration has not been studied systematically and may be under-recognised. Having a high level of suspicion and care strategies to ensure optimal fluid intake such as prompting older people to drink are important preventative measure. Specific treatment depends on the clinical assessment and may include IV fluid replacement, preventing venous stasis, pressure ulcers and falls, as well as managing the underlying cause, and uncontrolled hyperglycaemia. Care must be taken not to over hydrate the individual and cause cerebral oedema or water intoxication.

Depression and older people with diabetes

Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes in older people, the fact that depression is a risk factor for diabetes, the 2-fold increased risk of depression in people with diabetes (Bogner 2007), it is likely that many older people have undetected diabetes as well as undetected depression. Undiagnosed depression contributes to physical and mental functional impairment.

Depression frequently precedes and may be the cause of placement in an aged care facility. Depression may be due to grief over loss of functional and self-care ability and independence (Fleming 2002) and is significantly correlated with quality of life (Goldney et al. 2004). Depression is often associated with diabetes-related complications such as cardiovascular disease (Fenton 2006) and is more likely to be recurrent in older people (Cluning 2001), and leads to inadequate self-care, unstable blood glucose patterns, and affects cognitive functioning. Treating depression in older people reduces mortality by 50% (Bogner et al. 2007).

Some clues to the presence of depression in older people are:

- Talking about physical symptoms and believing they have a serious illness (Cluning, 2001).

- Grief over lost opportunities, abilities, and self-determination.

- Withdrawing from communal activities.

- Experiencing chronic pain.

- Having had a stroke or MI.

- Not receiving any visitors at least once a week in hospital and aged care facilities.

- Difficulty establishing relationships with staff and other aged care residents in the first four weeks after admission.

Depression management is discussed in Chapter 15. When possible, non-pharmacological options should be used first.

Differentiating depression from dementia

The prevalence of dementia increases with age and ranges from 63% to 81% (Zimmerman 2007). Approximately one-in-4 Australians over age 85 have dementia (Gray et al. 2002). There are two main forms of dementia: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) accounting for 70% of known dementias and Vascular Dementia (VD) accounting for the remaining 20%. Both AD and VD are present in ∼20% of people especially those with diabetes (Stewart & Liolitsa, 1999).

The association between diabetes and dementia may be due to:

- Cardiovascular disease: TIAs and stroke that can cause multifocal brain damage.

- Hypoglycaemia, especially if it is frequent and recurrent, which may cause permanent neuronal destruction.

- Persistent hyperglycaemia increases protein glycosylation and contributes to the development of advanced contributes to AGE (see Chapter 8) found in AD plaques (Phillips & Popplewell, 2002).

Nay and Garratt (1999) outlined three main stages of AD. The first is characterised by absent-mindedness, emotional instability and poor concentration. These symptoms can include spatial disorientation, disturbed perception, changes in personal appearance and hygiene, a tendency to blame others for a range of occurrences, and an inability to successfully perform ADLs. Depression is often present in the early stages because the person is aware that something is ‘not quite right’ and they realise ‘things are slipping away’ from them (Katona, 1994).

Stage two can last up to 12 years. The person may withdraw and behaviour is often variable including anger, transient crying, poor sleep patterns, disorientation, and profound short-term memory loss. Gait often changes, people have difficulty recognising their own face in a mirror, and continence issues emerge as well as other behaviours such as exhibitionism. The person cannot live safely by themselves in the community.

Stage three is often the shortest, lasting up to 2 years. Profound physical and cognitive decline occurs, finally resulting in stupor and coma. Miller (1999) developed a useful process for distinguishing between depression and dementia.

Managing diabetes in older people

Age, life expectancy, other health problems and the person’s social situation should be taken into account when planning care. Achieving near normal blood glucose levels and preventing long-term complications may not be priority management aims. It is important to control uncomfortable symptoms (polyuria, polydipsia, lethargy), maintain quality of life (QoL) and minimise the risk of hypoglycaemia and the attendant risk of falling.

Suboptimal metabolic control is associated with urinary incontinence, leg/foot ulcers, infections, nutritional deficiencies, exacerbation of neuropathic pain, affects the ability to communicate and cause confusion and aggression (Kirkland 2000). Strategies and priorities need to be implemented using a stepwise approach and non-pharmacological measures where possible.

Management aims

The issues outlined in the DHS, UK, and other policies and guidelines provide a useful framework for planning care. The main aims of care are to:

- Improve nutrition.

- Prevent hypo-and hyperglycaemia.

- Undertake a structured medication management programme using a quality use of medicine framework.

- Proactively screen for and prevent and/or manage diabetic complications, comorbidities, depression, and maintain independent self-care as long as possible.

- Undertake general preventative health measure such as vaccinations and health checks, for example, mammograms, prostate checks. Flu vaccine prevents respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, hospital admissions and death in older people (Gross et al. 1995). However, in years without influenza, booster vaccinations may not confer added benefits if routing trivalent vaccination does not produce seroprotection (Gaughran et al. 2007). Research suggests people with chronic diseases are less likely to receive preventative care despite attending health professionals frequently (Beckman et al. 2001; Lipscombe et al. 2005).

- Manage coexisting illnesses to improve functional ability and improve quality of life.

- Maintain a positive attitude.

- Maintain a safe environment to limit adverse events such as falls.

- Have plan for regularly assessing driving safety and help the individual develop and maintain a transportation plan to make the transition to stop driving. Be aware that operating motorised wheelchairs, Go-Fors, and farm machinery may also constitute a driving risk.

- Ensure a comfortable and peaceful death at the end of life.

Factors that affect management decisions

- Age, but age alone may not give an accurate picture of an individual’s ability to cope with self-care tasks and activities of daily living. Functional level should be assessed using appropriate tools in an appropriate familiar setting.

- Current diabetes control and complication status including the presence of liver and kidney disease.

- Presence and severity of comorbidities.

- Life expectancy.

- Mental and physical capacity to self-care.

- Nutritional status. Inadequate nutrition predisposes the person to hypoglycaemia, falls, decreased immunity, delayed wound healing and infections, and other diseases.

- Learning capacity, which is influenced by the individual’s learning style, sight, hearing and cognitive ability, interest in the topic, and the way the individual presents the information, see Chapter 16.

- Social support from family and the community.

- Financial status and access to services.

Nutritional management

Elderly people are often malnourished. In hospital, malnourishment is associated with longer length of stay and increased mortality (Middleton et al. 2001). The causes of poor nutrition are shown in Table 12.4. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between the effects of malnutrition and disease processes, which are closely related (World Health Organisation 1999).

It is important to take a broad approach to nutritional management in older people with diabetes rather than the usual focus on reducing fat and sugar. In addition, older people need to be encouraged to:

- Incorporate omega-3 foods into the diet.

- Eat a variety of nutritious foods in at least three meals every day.

- Eat plenty of cereals, wholegrain bread and pasta especially those with a low Glycaemic Index; 50–60% of total intake.

- Have adequate protein intake, consisting of at least 15% of the total intake.

- Eat plenty of fruit and vegetables to reduce the risk of cardiovascular and degenerative diseases and supply essential vitamins and minerals, such as calcium.

- Have an adequate fluid intake, including water (about 1500 millilitres per day) to reduce the likelihood of dehydration, especially in hot weather, unless fluid restriction is indicated.

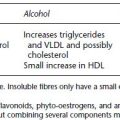

- Drink alcohol in moderation. Because of the reduced muscle mass, the volume in which alcohol is distributed is reduced; therefore, the concentration of circulating alcohol is higher, putting the person at risk of cognitive impairment, hypoglycaemia, and falls. However, moderate consumption of alcohol might have health benefits.

- Use low salt food and only add small amounts of salt to food to help prevent hypertension (National Health and Medical Research Council 1999).

Table 12.4 Risk factors for inadequate nutrition and malnutrition in older people.

| Risk factor | Potential outcome |

| Living in an institution | Forced food choices, loss of control over environment, depression |

| Malabsorption | Bacterial infections, coeliac disease, medicines, disease processes and diabetes complications |

| Neurological deficits | Stroke, dementia |

| Medicines | Digitalis, alcohol, sedatives |

| Sensory deficits | Impaired sight and/or hearing, taste and smell |

| Dentition and swallowing difficulties | Ill-fitting dentures, caries, missing teeth, gum disease, malnutrition |

| Social circumstances | Isolation, poverty, inability to shop or prepare food, depression, malnutrition |

| Medical problems | Chronic disease, pneumonia, heart failure, chronic infection, thyroid disease, malnutrition |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree