Chapter 64 Dermatologic Disease

Cutaneous disorders occur nearly universally during the course of HIV disease as a result of acquired immunodeficiency or related to treatment. Management of dermatologic conditions in HIV disease is a very broad subject, overlapping many other medical specialties.1 Individuals who have access to highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), in most cases those living in North America, Western Europe, and Australia, have a markedly altered course of HIV disease if immune restoration is achieved. In most cases, there is a marked reduction in the incidence of opportunistic infections (OIs) and neoplasms (ONs). Globally, however, more than 95% of those HIV-infected individuals have no access to any medical interventions. Despite estimates by the World Health Organization that at least 4.4 million people in sub-Saharan Africa (the region with the highest number of people living with HIV/AIDS) were in need of treatment with antiretroviral therapy in 2003, only ∼100 000 people were on therapy.2 Consequently, many of the cutaneous manifestations associated with HIV disease become chronic and progressive. Furthermore, the incidence and severity of cutaneous manifestations of HIV, including molluscum contagiosum, herpes simplex, oropharyngeal candidiasis, secondary syphilis, papular pruritic eruptions and seborrheic dermatitis among others, may serve as indicators of CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts and CD4:CD8 ratios, particularly in the developing world.3

ACUTE HIV INFECTION (PRIMARY RETROVIRAL SYNDROME)

Mucocutaneous findings in acute HIV infection include “rash” (50–60%; Fig. 64-1), oral candidiasis (17%), oral ulcers (10–20%), and genital ulcers (5–15%).4,5 Individuals with problematic rash or ulceration(s) should be treated symptomatically, as well as with HAART. Though it is important to recognize and treat a variety of sexually transmitted disease that may be co-transmitted with acute HIV infection, studies report that between 34% and 60% of genital ulcers have no proven etiological agent and may be related to HIV-mediated aphthous ulceration. In up to 12% of cases, mixed etiologies may be responsible for genital ulceration.6 Symptomatic candidiasis can be treated with topical or systemic anticandidal therapy (see section on Cutaneous Candidiasis).

CUTANEOUS DISORDERS OCCURRING WITH HIV DISEASE

Pruritus and Pruritic Eruptions in HIV Disease

Pruritus, a common complaint in patients with late symptomatic and advanced HIV disease, is a surrogate cutaneous marker for disease progression, occurring commonly in patients with CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts less than 50 cells/μL compared with those with counts over 250 cells/μL.7 In most cases, primary or secondary dermatoses rather than metabolic disorders are the cause of pruritus.8 The differential diagnosis of primary pruritic skin disorders includes eosinophilic folliculitis (EF) (Fig. 64-2), papular pruritic eruption of HIV, adverse cutaneous drug eruptions, atopic dermatitis, xerosis, dermatographism, allergic contact dermatitis, scabies, and insect bites.9 Much less commonly, systemic and metabolic disorders such as lymphoma, renal failure, viral hepatitis (hepatitis B or C), or obstructive liver disease are associated with pruritus in the absence of cutaneous findings, i.e., “metabolic” pruritus.10

An atopic diathesis (characterized by personal or family history of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and allergic rhinitis), which exists in up to 20% of the general population, may become manifest in individuals with advanced HIV disease and pruritus. Changes secondary to chronic rubbing and scratching include excoriations, atopic dermatitis, lichen simplex chronicus, and prurigo nodularis (Fig. 64-3). Up to 50% of HIV-infected individuals are Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriers. Secondary S. aureus infection (impetiginization, furunculosis, or cellulitis) is very common in any of these traumatized lesions. Ichthyosis vulgaris and xerosis are common in advanced HIV disease and may be associated with mild pruritus.

The protease inhibitors (especially indinavir) frequently cause xerosis with or without eczematous dermatitis, which may be associated with mild or moderate pruritus (see section on Adverse Cutaneous Drug Reactions). These changes occur relatively soon after initiation of therapy, presenting with xerosis (dry skin) with or without eczematous dermatitis or nummular eczema. Exanthematous drug eruptions such as those caused by trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) occur relatively suddenly and are easily associated with a newly prescribed drug.

Therapy

Control of pruritus is of great importance, in that scratching or rubbing the skin both causes as well as compounds the eczematous dermatitis. Oral doxepin is an excellent antipruritic agent taken at bedtime, the adult dosing varying from 10 to 200 mg. Many other less sedating antihistaminic agents are also effective for daytime or bedtime dosing. Gabapentin may also be helpful in dosages between 300 and 1800 mg/day, which can be titrated over a month according to symptoms. In recalcitrant cases, as is seen in prurigo nodularis, thalidomide in doses ranging from 33 to 200 mg/day, has been shown to be beneficial. Neurological examination is essential, as up to one-third of patients may developperipheral neuropathy.11

Eosinophilic Folliculitis

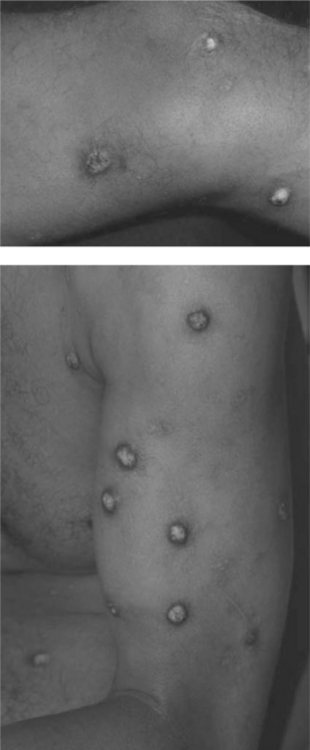

EF is a chronic dermatosis occurring in persons with advanced HIV disease or in those with immune restoration associated with HAART. The etiology and pathogenesis are unknown. Symptoms of EF usually occur when the CD4+ T-lymphocyte cell count is under 100 cells/μL; however, with HAART, EF occurs initially, recurs, or flares as immune restoration occurs and viral load levels fall (Fig. 64-2). As association with nadir in CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts less than 70 cells/μL has also been noted.12

Although subjective and objective findings of early EF are nearly pathognomonic, subacute or chronic EF may have many secondary changes, which make a clinical diagnosis tentative. In these cases, diagnosis of EF should be confirmed by the histologic findings. Peripheral eosinophilia is common in HIV-associated EF, in some cases, up to 35%.13

Therapy

Several orally administered agents have been reported to be effective in treatment of EF. Oral isotretinoin is effective and safe in treatment of EF, usually 40 mg bid until lesions and symptoms resolve, then tapered to 40 mg daily for several weeks, and then to 20 mg daily or 40 mg qod.14 Isotretinoin can raise serum triglyceride levels, which are often high in HIV-infected persons; serum lipid should be monitored regularly. Isotretinoin (as well as protease inhibitors) commonly causes cheilitis, eczematous dermatitis, and xerosis; these adverse effects can usually be managed with “moisturizing” agents and corticosteroid ointment.

Phototherapy with ultraviolet radiation (UVR), using ultraviolet A (UVA), ultraviolet B (UVB) with or without topical or systemic psoralen is considered to be a safe topical treatment modality in HIV-infected persons.15 UVR does not appear to have a significant deleterious effect on HIV viral load.16 UVB phototherapy of EF, given by skilled technicians to compliant patients, is effective in suppressing both lesions and symptoms. Compliance is an issue for many individuals in that treatment is usually given three times per week for 4–8 weeks, subsequently reducing the frequency of treatment as the skin clears.

High-potency topical corticosteroid preparations may reduce the formation of new EF lesions and cause established lesions to resolve, thus providing symptomatic relief. New lesions occur once corticosteroids are discontinued. There is a significant risk of cutaneous atrophy if corticosteroids are applied chronically. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% has been reported to be effective.16 Sedating antihistamines such as doxepin are most effective for symptomatic control of nocturnal pruritus; nonsedating antihistamines are ineffective in controlling pruritus.

Unlike EF, acne does not appear to be exacerbated by HIV.17 However, acne has been observed in those treated with androgel for hypogonadism in HIV disease.

Papular Pruritic Eruption of HIV

Papular pruritic eruption of HIV (PPE) represents significant morbidity to the HIV-infected individual, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. It has been classified with other pruritic disorders in HIV disease in the spectrum of EF and nonspecific pruritus. The prevalence is estimated between 12% and 46% in Africans and Haitians, and the disease is only rarely observed in Europe and North America. The positive predictive value of PPE for HIV infection is ∼85 %.18 In addition, it appears to be a marker of severe immunosuppression as over 80% of patients with this disorder have counts less than 100 cells/μL.19

The primary lesion is a firm urticarial papule (though sterile pustules have been described as well) and displays variable erythema distributed symmetrically on the trunk and extremities and less commonly on the face. It is occasionally but not always folliculocentric and may be associated with excoriations, postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and scarring which result from the intense pruritus caused by the disease. A recent report from studies in Uganda has suggested that PPE is a hypersensitivity reaction to arthropod bites based on histopathologic evaluation of skin biopsies. The authors proposed changing the name of this disorder to “arthropod-induced prurigo of HIV.”18

Atopic Dermatitis (Eczematous Dermatitis)

Eczematous dermatitis is managed by treating underlying causes such as xerosis, adverse cutaneous drug reactions, scabies, or metabolic pruritus. Potent corticosteroids or tacrolimus 0.1% ointment are the most effective topical agents for treatment of eczematous dermatitis. High potency, short-term dosing usually minimizes the use of topical corticosteroid preparations. In more severe cases, a 1–2 week tapered course of prednisone is indicated, beginning at an initial dose of 70 mg in adults. For patients with dermatitis recurring after prednisone, phototherapy is effective and safe (see section on Pruritus and Pruritic Eruptions in HIV Disease).20

Psoriasis Vulgaris

The prevalence of psoriasis vulgaris in HIV-infected individuals may be somewhat higher than that of the general population; that of psoriatic arthritis, however, is higher, correlating with the presence of HLA-B27. The onset of psoriatic lesions may be prior to or following HIV infection. Onset of psoriasis in an individual at risk for HIV disease may be an indication for HIV serotesting. Psoriasis and Reiter’s syndrome may coexist in the same patient, suggesting the two disorders may be part of a spectrum of clinical manifestations of one disease. Psoriasis with onset following HIV infection has been observed to improve more so with HAART than psoriasis noted prior to HIV infection.

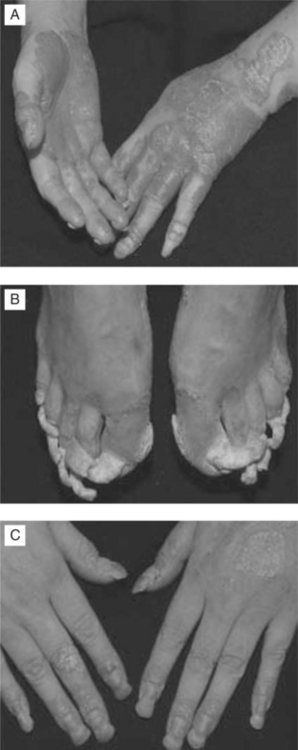

In a cohort of 50 HIV-infected individuals with psoriasis, one-third of psoriasis cases were presumed to have occurred prior to HIV infection (group I) and two-thirds after infection (group II). Group I had a lower mean age of onset (19 years vs 36 years) and more commonly had a family history of psoriasis. The clinical patterns of psoriasis (Fig. 64-4a–c) were reported to be plaque type (78%), inverse (37%), guttate (29%), palmoplantar (8%), erythrodermic (14%), and pustular (8%). Palmoplantar and inverse pattern psoriasis were more common in group II; severe psoriasis occurred in one quarter of these patients. Psoriasis tended to become more severe as the degree of immunodeficiency increased, but did not affect survival.

Therapy

Oral therapy with retinoids such as acitretin, methotrexate, and cyclosporin is indicated for persons with psoriasis that is unresponsive to topical steroids and phototherapy. Oral or intramuscular methotrexate given weekly is effective for psoriatic arthritis. Systemic therapy requires careful monitoring of lipids, complete white cell count and liver function tests. Successful treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with biologics such as etanercept and infliximab in the HIV-host exists in the form of case reports.21

Erythroderma

Erythroderma in HIV disease may be related to drug hypersensitivity, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis vulgaris, photosensitivity dermatitis, the hypereosinophilic syndrome and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In addition, rare infections such as histoplasmosis and coexistent HTLV-I infection may present as erythroderma in the HIV host.22

Xerosis and Ichthyosis

Therapy

Xerosis is best treated with application of “emollient” creams after bathing. Products with hydroxy acids are keratolytic and hydrophilic. In persons with chronic xerosis, eczematous dermatitis can occur within fissures in areas of hyperkeratosis, i.e., eczema craquelé or asteatotic eczema (see section on Atopic Dermatitis (Eczematous Dermatitis)).

Photosensitivity

Idiopathic photosensitivity is an increasingly recognized phenomenon in HIV disease, and may be the presenting complaint.23,24 African-American ethnicity and HAART appear to be independent risk factors for development of disease, which presents mostly as lichenoid or eczematous dermatitis.25 The most common types of photosensitivity in HIV disease are related to drug therapy. Drug-induced photosensitivity reactions are of two types; phototoxic, which occurs in all individuals and is essentially an exaggerated sunburn response (erythema, edema, vesicles, e.g., TMP-SMX), and photoallergic, which involves an immunologic response in which the eruption is papular, vesicular, eczema-like, and occurs only in previously sensitized individuals. Drug-induced photosensitivity reactions are most commonly caused by UVA, and to a much lesser extent UVB. Photosensitivity in HIV disease appears to be a manifestation of advanced disease (see section on Porphyria Cutanea Tarda).26

Therapy

In management of photosensitivity, a photosensitizing agent should be identified and discontinued if possible. If the offending drug cannot be discontinued, sunlight should be avoided; sunscreen and protective clothing should be recommended. Phototoxic drug reactions disappear after cessation of the drug. Photoallergic drug reactions can persist for months or years after the drug is discontinued (known as persistent light reaction or chronic actinic dermatitis). In severe cases of photoallergic dermatitis topical or systemic corticosteroids or other agents such as nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or pentoxifylline are indicated.27

APHTHOUS ULCERS

Recurrent and/or persistent aphthous ulcers (AUs) complicate advanced HIV disease, arising in the mouth, oropharynx, and esophagus (see Chapter 65). AU-like lesions occur on the external genitalia during the course of acute HIV infections. AU of the upper mouth and esophagus frequently cause moderate to severe pain, impairing eating and speaking, and are associated with significant weight loss. The incidence appears to be reduced with HAART.

Therapy

Individual AUs of the anterior mouth and oropharynx usually respond to intralesional triamcinolone injection; deeper lesions, however, cannot be treated with this effective, low-risk modality. Prednisone is usually quite effective in treatment of persistent AUs; most AUs resolve with an initial dose of 70 mg tapered by 10 or 5 mg/day. In persons in whom prednisone is contraindicated or ineffective, thalidomide 50–200 mg HS is an effective alternative medication.28 The most common adverse events occurring with thalidomide are neutropenia, rash, and peripheral sensory neuropathy.

CUTANEOUS MANIFESTATIONS OF SYSTEMIC DISORDERS OCCURRING IN HIV DISEASE

Porphyria Cutanea Tarda and Pseudoporphyria

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) in HIV disease is most often associated with an underlying hepatopathy (hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, alcoholism, or hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection).29 The HIV virus is thought to inhibit the cytochrome oxidase system, thereby affecting porphyrin metabolism.30 In one study, 40% of patients (n 5 33) with advanced HIV disease had increased urinary porphyrin excretion; 31 patients were herpes simplex virus (HSV)-seropositive; four patients had urine and stool porphyrin excretion patterns that were classic for PCT.31 No study patient, however, had clinical evidence of PCT. Thus, porphyrin studies are recommended for HIV-infected individuals with photosensitivity. Clinically, PCT presents with blisters, erosions, crusts, milia on the dorsum of the hands as a manifestation of photosensitivity. Hyperpigmentation and hypertrichosis often occur on the face.

Vasculitis

Cutaneous and systemic vasculitis of many etiologies have been reported to occur in HIV disease, including adverse cutaneous drug reaction, erythema elevatum diutinum, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, polyarteritis nodosa, and Kawasaki’s disease, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and possibly HIV infection itself.32 Causative drugs should be discontinued if possible. Most other causes are not specifically treatable. Systemic immunosuppressive therapy may be indicated in some cases.

Autoimmunie Disorders

Immune reconstitution following therapy with HAART may exacerbate or induce autoimmune disorders. Generally, immunosuppression caused by HIV infection improves conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus. Systemic, tumid and discoid lupus have been reported soon after initiation of HAART.33,34 Though tumid and discoid lupus may respond to antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine 200 mg orally twice a day, systemic lupus usually requires systemic immuno suppression. Immune reconstitution may also induce vitiligo and sarcoid.35–37 Mycobacterial infection must be excluded before a diagnosis of sarcoid is made. On the other hand, autoimmune symptoms have also been linked to HIV infection in the absence of immune reconstitution. Rheumatoid arthritis, reactive arthritis, diffuse interstitial lymphocytosis syndrome, subcorneal pustular dermatosis and pemphigus vulgaris have been reported in HIV disease.38,39

OPPORTUNISTIC CUTANEOUS INFECTIONS IN HIV DISEASE

Bacterial Infections

S. aureus causes the majority of all pyodermas and soft-tissue infections (Fig. 64-5). Colonization of the anterior nares occurs in greater than 50% of HIV-infected individuals. From 1997 to 2000, it was the most common bacterial isolate in HIV-positive individuals, unlike HIV-negative individuals who are most frequently colonized by coagulase-negative Staphylococci. In addition, the number of isolates that are methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), as well as methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative Staphylococci is increasing in HIV-positive individuals over the rate noted in HIV-negative counterparts.40 In a recent study of HIV-positive men who have sex with men, the frequency of community acquired MRSA was associated with high-risk sexual and drug-using behaviors but not with immune status.41 Intravascular catheters and cutaneous infections are the most common sources of S. aureus bacteremia.

Rarely, as the result of trauma, S. aureus can infect the skin in the form of deep nodules, ulcers or verrucous plaques that discharge granules via sinuses. Lesions are usually found in the lower extremities and may be tender and pruritic. Botryomycosis in the HIV host is a chronic disease and diagnosis is made on histopathology and culture. Antibiotics are usually not sufficient to eradicate infection, and surgical excision is recommended. The disease is mostly cutaneous, though visceral botryomycosis has been reported.42

Therapy

Gram-negative folliculitis may be observed in HIV disease. Patients present with follicularly based papules and pustules, that may be occasionally tender or pruritic. Diagnosis is made by culture. Therapy, though initially empiric, should be guided by antibiotic sensitivities. Recently, Acinetobacter baumanii folliculits was reported in patients with AIDS. The patient cleared after treatment with intravenous ticarcillin/clavulanic acid (3 g/200 mg) four times daily.43

Bacillary Angiomatosis

Bacillary angiomatosis (BA) and bacillary peliosis (BAP), caused by the genus Bartonella, B. henselae and B. quintana, occur most commonly in the setting of HIV-induced immunodeficiency, characterized by angioproliferative lesions resembling cherry hemangiomas, pyogenic granulomas, or Kaposi sarcoma (KS) (see Chapter 42; Fig. 64-6).44,45 Lesions maybe multiple, varying in size from 1 mm to several centimeters, or may present as a single, painful, subcutaneous nodule. Currently, the prevalence of BA in North America and Western Europe is very low due to improved immune function with HAART and to prophylaxis given for infections such as Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC).46 Diagnosis may be delayed because the organism is difficult to culture. Serological studies are plagued by cross-reactivity between organisms in the species. Histopathological examination with Warthin–Starry silver stain can help in diagnosis, but does not differentiate among species.

Therapy

Treatment should include either clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily, azithromycin 250 mg once daily, erythromycin 500 mg four times a day, or doxycycline 100 mg twice a day fora period of at least 4 weeks (see Chapter 42). Alternative therapies include rifampin, fluoroquinolones or TMP-SMX.47

In developing countries, tuberculosis is the most common OI in HIV disease; however, cutaneous tuberculosis is relatively uncommon. In non-HIV-infected persons with tuberculosis, the incidence of extrapulmonary tuberculosis is 15%; in HIV disease it is 20–40%. In advanced HIV disease, the incidence of extrapulmonary disease increases to 70% (see Chapter 40).

Tuberculosis

Lichen scrofulosorum is very rare and found in young individuals. It presents as very small erythematous papules with superficial scale that surround the hair follicles and heal without scarring. Erythema induratum of Bazin presents as an erythematous painful nodule, usually in the posterior, lower extremities. It is most common in women, and may ulcerate and heal with atrophic scars. In 2005, five cases of a “new” subtype were described and were termed ‘nodular tuberculid’. Like erythema induratum, nodular disease also presents as erythematous nodules, but granulomatous vasculitis is observed additionally on histopathologic evaluation.48 Treatment for tuberculids is geared at eradicating infection with multiple-agent antibiotic regimens. Supportive care for cutaneous hypersensitivity with topical steroids, emollients and antipuritics can be helpful.

Fungal Infections

Cutaneous fungal infections occur as superficial infections (dermatomycoses), invasive fungal infections, or hematogenous dissemination of systemic fungal infection to the skin. The two most common dermatomycoses are dermatophytoses and candidiasis; both of these infections occur with increased frequency in the setting of compromised local or systemic immunity.

Dermatophytoses

Dermatophytes, especially Trichophyton rubrum, can infect any keratinized epidermal structure, i.e., epidermis (tinea pedis, tinea cruris, tinea manuum, tinea corporis, tinea facialis, tinea incognito), nails (tinea unguium or onychomycosis) and hair (tinea capitis, tinea barbae, dermatophytic folliculitis).49,50 Dermatophytes infect nonviable tissue in otherwise healthy individuals, however, in the compromised host, direct invasion of the dermis may occur. Up to 20% of HIV-positive patients with cell counts below 400 cells/μL will develop dermatophytic infections.51 Dermatophytoses are of importance for three reasons: the morbidity and disfigurement caused by the dermatophyte infection itself, which can be quite extensive; the breakdown in the integrity of the skin that can occur, providing a portal of entry for other pathogens, particularly S. aureus; and also because such infections can cause clinical manifestations that mimic other dermatologic conditions.52 For instance, widespread infection with Trichophyton rubrum can mimic KS.53 Dermatophyte infections in the compromised host are more frequent, often widespread, atypical in appearance, or invasive.54

Trichophyton rubrum causes proximal subungual onychomycosis (PSO), an infection of the undersurface of the proximal nail plate. PSO occurs most often in HIV-infected individuals; the diagnosis is an indication for HIV testing. Unless immunocompetence is restored, dermatophyte infections are chronic and recurrent.55

Therapy

Dermatophyte infections are managed with systemic as well as topical antifungal agents (Table 64-1). Infections of the epidermis (Table 64-1), nail apparatus (Table 64-2), and hair/hair follicle (Table 64-3) cannot be cured by topical agents alone, especially in the setting of immunocompromise. Though precautionary information abounds regarding combination of antiretroviral medications with antifungal agents, little data exists to support adverse effects, with the exception of combination therapy with indinavir and ketoconazole.56 The HIV-infected patients who are taking oral imidazoles such as fluconazole or itraconazole for candidiasis or cryptococcosis, are also inadvertently treating dermatophytoses. Terbinafine, which is highly efficacious for dermatophytic infection, is not predictably effective for nondermatophytic fungal infections.

Table 64-1 Agents Used in the Management of Dermatophyte Infections

| Parameter | Comments |

|---|---|

| Prevention | Immune restitution with HAART markedly reduces the incidence of dermatophyte infections. |

| Apply powder containing miconazole or tolnaftate to areas prone to fungal infection after bathing. | |

| Topical antifungal preparations | These preparations may be effective for treatment of dermatophytoses of skin but not for those of hair or nails. Topical agents should be continued for at least 1 week after lesions have cleared. Apply at least 3 cm beyond advancing margin of lesion. |

| These agents are comparable. Differentiated by cost, base, vehicle, and antifungal activity. Preparation is applied twice a day to involved area optimally for 4 weeks. | |

| Imidazoles | Clotrimazole (Lotrimin, Mycelex) |

| Miconazole (Micatin) | |

| Ketoconazole (Nizoral) | |

| Econazole (Spectazole) | |

| Oxiconazole (Oxistat) | |

| Sulconazole (Exelderm) | |

| Allylamines | Naftifine (Naftin) |

| Terbinafine (Lamisil) | |

| Naphthiomates | Tolnaftate (Tinactin) |

| Substituted pyridone | Ciclopiroxolamine (Loprox) |

| Systemic antifungal agents | For infections of keratinized skin: use if lesions are extensive or if infection has failed to respond to topical preparations. |

| Usually required for treatment of tinea capitis and tinea unguium. Also may be required for inflammatory tineas and hyperkeratotic moccasin-type tinea pedis. | |

| Terbinafine | 250 mg tablet. Allylamine. |

| Azole/imidazoles | Itraconazole and ketoconazole have potential clinically important interactions when administered with calcium-channel antagonists, warfarin, cyclosporin A, tacrolimus, oral hypoglycemic agents, phenytoin, protease inhibitors, terfenadine, theophylline, trimetrexate, and rifampin. |

| Itraconazole | Capsules (100 mg); oral solution (10 mg/mL); intravenous iriazole. Needs acid gastric pH for dissolution of capsule. |

| Fluconazole | Tablets (100, 150, 200 mg); oral suspension (10 or 40 mg/mL); 400 mg IV. |

| Ketoconazole | Tablets (200 mg) (little used currently). |

Table 64-2 Management of Dermatophytic Infections of the Nail Apparatus

| Agent | Comments |

|---|---|

| Débridement | Dystrophic nails should be trimmed. In DLSO the nail and the hyperkeratotic nail bed should be removed with nail clippers. In SWO the abnormal nail can be debrided with a curette. |

| Topical agents | Available as lotions and lacquer. Usually not effective except for early DLSO and SWO after prolonged use (months). |

| Amorolfine nail lacquer: reported to be effective when applied >12 months (available in Europe). | |

| Penlac: monthly professional nail debridement recommended. | |

| Systemic agents | During systemic treatment of onychomycosis, nails usually do not appear normal after the treatment times recommended because of slow growth of nail. If cultures and KOH preparations are negative after these time periods, medication can nonetheless be stopped and the nail usually regrows normally. |

| Allylamines | Most effective against dermatophyte infections; also efficacious against select other fungi. |

| Terbinafine | Dose: 250 mg/day for 6 weeks for fingernails and 12 weeks for toenail. |

| Azoles | Drugs in this category are usually effective for treating nail infections caused by dermatophytes, yeasts, and molds. |

| Itraconazolea | Continuous therapy with 200 mg daily for 6 weeks (fingernails) or 12 weeks (toenails). |

| Dose: 200 mg bid for first 7 days of each month for 2 months (fingernails) (pulse dosing). Although not approved for toenail onychomycosis, pulse dosing is used for 3–4 months. | |

| Fluconazolea | Reported effective at dosing of 150–400 mg 1 day/week or 100–200 mg daily until the nails grow back normally. Effective against yeasts and less so for dermatophytes. |

| Secondary prophylaxis | Recommended for all patients. The entirety of both feet should be treated. |

| Prophylaxis should be simple to use and inexpensive. | |

| Benzoyl peroxide bar for washing feet when bathing. | |

| Antifungal cream daily. | |

| Zeaborb (miconazole) AF lotion/powder on feet. | |

| Antifungal sprays or powders in shoes. |

DLSO, distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis; SWO, superficial white onychomycosis; KOH, potassium hydroxide.

a Effective against dermatophytes and Candida.

Table 64-3 Management of Dermatophytic Infections of the Hair Shaft/Hair Follicle

| Parameter | Comments |

|---|---|

| Prevention | Important to examine home and school contacts of affected children for asymptomatic carriers and mild cases of tinea capitis. Ketoconazole or selenium sulfide shampoo may be helpful for eradicating the asymptomatic carrier state. |

| Topical antifungal agents | Topical agents are ineffective for management of tinea capitis. Duration of treatment should be extended until symptoms have resolved and fungal cultures negative. |

| Oral antifungal agents | Of the systemic antifungals available, terbinafine and itraconazole are superior to ketoconazole, and all three are superior to griseofulvin. Side effects in increasing order: terbinafine, itraconazole, ketoconazole, griseofulvin. |

| Terbinafine | Dose: 250 mg qd. Reduce dosing according to weight in pediatric patients. |

| Itraconazole | Dose: 100 mg capsules or oral solution (10 mg/mL). Treatment duration: 4–8 weeks. Pediatric dose 5 mg kg−1 day−1; adult dose 200 mg/day. |

| Fluconazole | Tablets (100, 150, 200 mg); oral solution (10 and 40 mg/mL). Dosage: 6–8 mg−1 kg day−1. Treatment duration 3–4 weeks. Pediatric dose 6 mg kg−1 day−1 for 2 weeks; repeat at 4 weeks if indicated; adult dose 200 mg/day. |

| Ketoconazole | Tablets (200 mg). Treatment duration 4–6 weeks (little used currently). Pediatric dose 5 mg kg−1 day−1; adult dose 200–400 mg/day. |

| Adjunctive therapy | |

| Prednisone | Dose: 1 mg kg−1 day−1 for 14 days for children with severe, painful kerion. |

| Systemic antibiotics | For secondary S. aureus or group A streptococcal infection: clindamycin, dicloxacillin, or cephalexin. |

| Surgery | Drain pus from kerion lesions. |

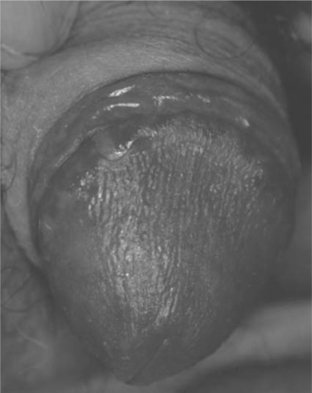

Cutaneous Candidiasis

Cutaneous Candida infections such as intertrigo, are common in adults with HIV disease (Table 64-4); concomitant diabetes mellitus associated with HAART may increase the prevalence. Candidiasis of moist, keratinized cutaneous sites such as the anogenital region occurs with some frequency in up to 90% of HIV-infected individuals (Fig. 64-7).51 Candidal angular cheilitis occurs at the corners of the mouth as an intertrigo, unilaterally or bilaterally, and is more common in edentulous patients; it may occur in conjunction with oropharyngeal or esophageal disease or as the only manifestation of candidal infection. Children with HIV infection commonly experience candidiasis in the diaper area, intertrigo in the axillae and neck fold. Fingernail chronic Candida paronychia with secondary nail dystrophy (onychia) is common in HIV-infected children.57

Table 64-4 Classification of Candidiasis Involving Skin and Mucosa

| Type | Site | Clinical Presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Occluded site (occurs where occlusion and maceration create warm, moist microecology) | Body folds | Axillae, inframammary, groins, intergluteal, abdominal panniculus |

| Webspace: hands (erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica), feet | ||

| Angular cheilitis; often associated with oropharyngeal candidiasis | ||

| Genitalia | Balanitis, balanoposthitis | |

| Vulvitis | ||

| Occluded skin | Under occlusive dressing, under cast, back in hospitalized patient | |

| Folliculitis | Back in hospitalized patient | |

| Area occluded under diaper | Diaper dermatitis | |

| Nail apparatus | Paronychium | Chronic paronychia |

| Nail plate | Onychia | |

| Hyponychium | Onycholysis | |

| Chronic mucocutaneous | Extensive, multiple or 20 nails | In HIV-infected children, persistent or recurrent mucosal, cutaneous, and/or paronychial/nail infections |

| Genital | Vulva, vagina; preputial sac | Erythema, erosions, white plaques of candidal colonies |

| Mucosal | Oropharynx | Thrush; atrophic candidiasis; hyperplastic candidiasis |

| Esophagus | Inflamed, eroded plaques | |

| Trachea, bronchi | Inflamed, eroded plaques | |

| Candidemia | Skin, viscera | Skin: erythematous papules 6 hemorrhage |

Therapy

Topical therapy is usually adequate, but systemic agents may be required in the setting of advanced immunocompromise (Tables 64-5 and 64-6). Chronic prophylaxis with fluconazole may lead to azole-resistance, and is currently not recommended unless CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts remain low or if recurrences are very frequent.51

Table 64-5 Management of Cutaneous Candidiasis

| Management | Comments |

|---|---|

| HAART | With immune restitution, candidiasis resolves and/or does not occur. |

| Prevention | Keep intertriginous areas dry (often difficult). |

| Washing with benzoyl peroxide bar may reduce Candida colonization. | |

| Powder with miconazole applied daily. | |

| Topical treatment | Brings almost immediate relief of symptoms (i.e., candidal paronychia). |

| Castellani’s paint | |

| Corticosteroid preparation | Judicious short-term use speeds resolution of symptoms. |

| Topical antifungal agents | Antifungal preparation: nystatin, azole, or imidazole cream bid or more often with diaper dermatitis. Tolnaftate not effective for candidiasis. Terbinafine may be effective. |

| Nystatin cream | Effective for Candida only. Not effective for dermatophytosis. |

| Azole creams | Effective for candidiasis, dermatophytosis, and pityriasis versicolor. |

| Oral antifungal agents | Eliminate bowel colonization. Azoles treat cutaneous infection. |

| Nystatin (suspension, tablet, pastille) | Not absorbed from the bowel. Eradicates bowel colonization. May be effective for recurrent candidiasis of diaper area, genitalia, or intertrigo. |

| Systemic antifungal agents | See table 64.5. |

HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Table 64-6 Management of Oropharyngeal Candidiasis

| Management | Comments |

|---|---|

| HAART | With immune restitution, candidiasis resolves and/or does not occur. |

| Topical agents | Effective in most cases. |

| Nystatin | Vaginal tablets: 100 000 units qid dissolved slowly in the mouth. |

| Oral suspension: 1–2 teaspoons held in mouth for 5 min and then swallowed. | |

| Clotrimazole | Oral tablets (troche), 10 mg: one tablet 5 times daily. |

| Systemic therapy | Systemic therapy indicated if OPC fails to respond to topical agents. |

| Fluconazole | Oral: 200 mg PO once followed by 100 mg daily for 2–3, weeks, then discontinue. Increase the dose to 400–800 mg in resistant infection. IV also available. |

| Itraconazole | Capsules or oral solution: 100–200 mg PO 100 mg PO qd or bid for 2 weeks. Increase dose with resistant disease. |

| Ketoconazole | 200 mg PO qd to bid for 1–2 weeks (little used currently). |

| Voriconazole | Investigational; may be useful for Candida species with relatively high MIC. |

| Fluconazole-resistant candidiasis | Defined as clinical persistence of infection following treatment with fluconazole 100 mg/day PO for 7 days. Occurs most commonly in HIV-infected individuals with CD4+ lymphocyte counts <50/mm3 who have had prolonged fluconazole exposure. Chronic low-dose fluconazole treatment (50 mg/day) facilitates emergence of resistant strains. |

| Amphotericin B | For severe resistant disease. New liposomal preparations are effective and less toxic. |

HAART, highly active antiretroviral therapy; MIC, minimal inhibitory concentration; OPC, oropharyngeal candidiasis.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree