Depression, Anxiety, and Fatigue

INTRODUCTION

Depression, anxiety, and fatigue are frequent complications of cancer and cancer treatment. Although fatigue can be caused by depression and anxiety, it is a separate symptom that often does not have psychological origins.

An estimated one-third of all people with cancer experience psychosocial distress. Psychosocial distress encompasses both psychiatric disorders as well as emotional states that do not meet full criteria for psychiatric illnesses. Depression, anxiety disorders, and adjustment disorders are the most common psychiatric disorders in cancer patients. Delirium, however, may be more prevalent in hospitalized cancer patients, affecting almost 25%.

REACTION TO DIAGNOSIS OF CANCER

A diagnosis of cancer can elicit a variety of emotions, including sadness, anxiety, anger, and fear. People may have difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite, anxious thoughts about their cancer, poor concentration, and low mood. These symptoms can persist for 3 weeks after diagnosis. Usually by 4 weeks after diagnosis, people have their coping mechanisms in place and the depressive and anxiety symptoms have resolved. Unless the psychological symptoms are severe or are markedly impairing functioning, the diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder is usually reserved during the first 4 weeks after diagnosis, while people are coping with learning they have cancer.

DEPRESSION

Depression can be used to describe a symptom, feeling sad, as well as a serious illness, major depressive disorder (MDD). MDD is associated with poor quality of life, worse adherence to treatment, longer hospital stays, greater desire for death, suicide, and, possibly, increased mortality (1).

PREVALENCE

PREVALENCE

In a recent meta-analysis the prevalence of depression in individuals with cancer by DSM or ICD criteria was 16.3% (13.4–19.5) and for DSM-defined major depression it was 14.9% (12.2–17.7); similarly the prevalence of clinical levels of depressive symptoms, not necessarily MDD, was 19.2% (9.1–31.9) (2).

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of MDD is made by using a set of diagnostic criteria that include having a persistently low mood and 5 of the following symptoms for at least 2 weeks: sleep disturbance; loss of interest or anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure); feelings of hopelessness, helplessness, or guilt; low energy; poor concentration; appetite disturbance; psychomotor retardation/agitation; and suicidal ideation. Because many of these symptoms overlap with cancer and cancer treatments, substitutive criteria have been proposed, such as the Endicott criteria. However, the different sets of criteria may not yield markedly different results and in clinical practice physical symptoms that could be related to cancer or cancer treatment are included in making the diagnosis of MDD (3).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

It is important to evaluate possible medical contributions to low mood and to consider the differential diagnosis. Untreated pain, hypothyroidism, and medications such as glucocorticoids and certain chemotherapies (alpha interferon, pemetrexed, and procarbazine) may contribute to MDD. The differential diagnosis includes:

• Adjustment disorder: Low mood has been present for less than 2 weeks or there are less than 5 of the symptoms needed for the diagnosis of MDD. Adjustment disorders are usually in response to a negative event. Treatment usually focuses on symptoms such as sleep disturbance, and antidepressants are usually not prescribed unless the symptoms persist or there is significant impairment in functioning.

• Delirium: Defined as a transient disturbance consciousness with reduced attention and generalized impairment of cognition, can present with waxing and waning severity of symptoms, and be accompanied by sleep-wake disturbance, language impairment, and psychotic symptoms, especially visual hallucinations and paranoid delusions. Agitation does not need to be present and in fact, one subtype of delirium, hypoactive delirium, presents with social withdrawal and inactivity, which is often mistaken for MDD. Addressing the underlying cause and the use of anti-psychotics, not antidepressants, are the treatment for delirium.

• Fatigue: Although difficult to tease apart from MDD, because of overlapping symptoms, attention to clinical symptoms can facilitate its diagnosis. Anhedonia (markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities) may be the best distinguishing factor for MDD. Depressed patients usually complain of fatigue early in the day, whereas energy levels in cancer-related fatigue are at its best at this time of the day. Severe hopelessness and suicidal ideation are usually less frequent in fatigue.

• Anxiety: Tearfulness and depressed mood can occur in anticipation of negative events, like disease progression or cancer recurrence. In this case the low mood is not persistent and is usually triggered by the anxious thoughts. However, anxiety and MDD often occur together.

• Personality disorders: Can present with depressed mood, but the mood symptoms are not usually constant and persistent. Mood changes are usually triggered by a perceived injury or threat of abandonment. People with personality disorders can have difficulties maintaining stable social support and a history of self-harmful behavior like cutting. Although antidepressants and other psychotropic medications may be useful in managing specific symptoms, the treatment of personality disorders is primarily behavioral.

• Apathy: A neurological symptom that can also look like MDD and it is associated with a lesion in the frontal or temporal lobes. There is little spontaneous action or speech; responses are delayed, short, slowed, or absent; and it is usually associated with cognitive impairment and older age. Stimulants and dopaminergic medications may be helpful.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Treatment for MDD consists of antidepressants and/or psychotherapy. Severe cases of MDD, especially those that endanger a patient’s life, may be treated with electroconvulsive therapy. Although complementary treatments such as herbal preparations, acupuncture, and massage are available, there is currently little data on their efficacy for treating MDD in cancer patients. Suicidal ideation should be assessed and, if present, a referral to a mental health professional should be made.

Antidepressants

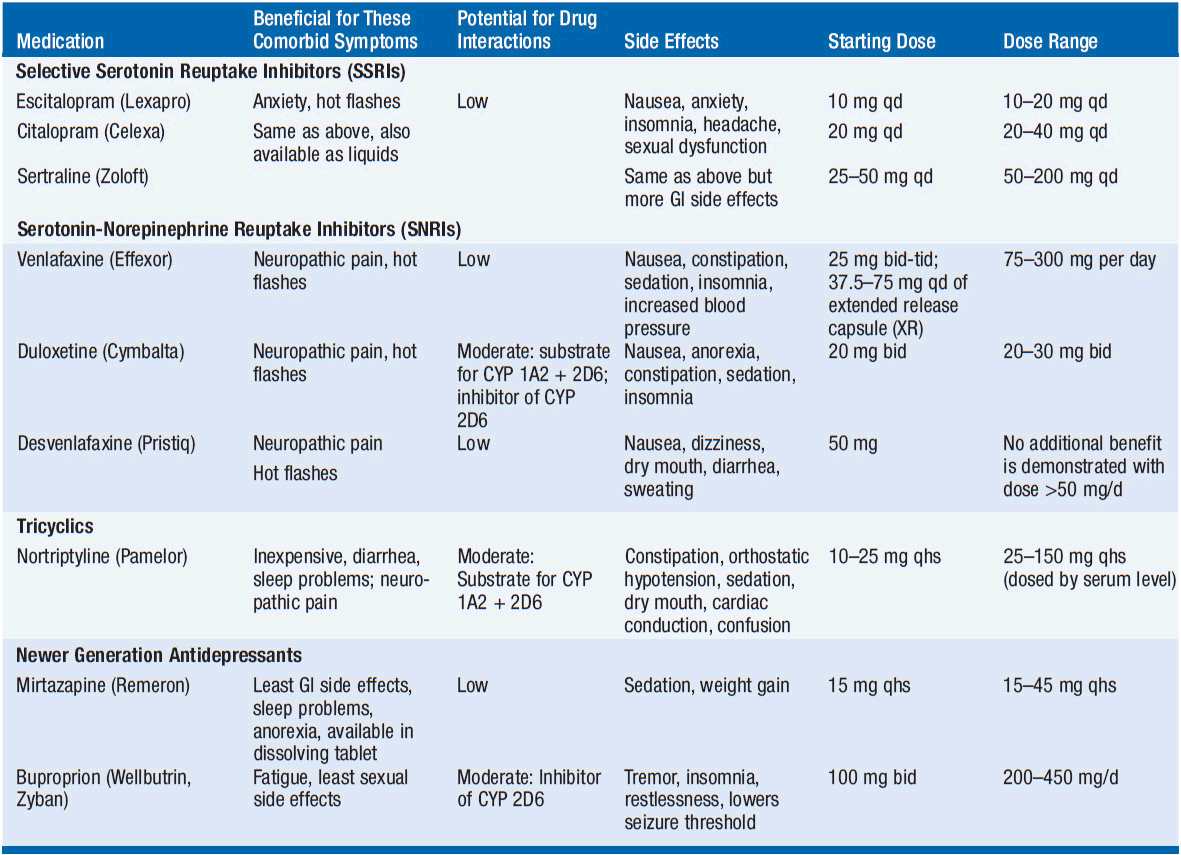

Antidepressants are commonly used to treat MDD comorbid with cancer (Table 23-1). Overall, limited evidence from three randomized trials and two trials comparing active treatments suggest that cancer patients may benefit from pharmacological treatments of depression (4). Antidepressants should be selected with potential side effects in mind. Side effects can impact tolerability, but also be helpful with accompanying symptoms such as sleep disturbance and poor appetite. Some of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, and paroxetine) and buproprion may interfere with the metabolism of commonly used medications in oncology because of their effects on cytochrome p450 2D6 system (5). Additionally, the FDA recently warned of higher doses of citalopram leading to QT prolongation and arrhythmias, especially when used with medications altering its metabolism (6). Antidepressants usually take about 4 weeks to see full benefit, but some patients may show signs of improvement earlier. Antidepressants should be continued for 9–12 months after remission of depressive symptoms if this has been the person’s first episode. Patients with recurrent MDD should continue the medication longer in order to lessen the chances of recurrence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree