Major Concepts

Symptoms

Infection with dengue virus leads to either dengue fever (DF), dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF), or dengue shock syndrome (DSS). DF is an extremely painful febrile illness likened to the pain of having many broken bones. It is self-limiting and typically resolves within ten days except for transient fatigue and depression. DHF is a severe, life-threatening form of the disease that primarily affects children under the age of 15 years. Its symptoms include fever, profound abdominal pain, liver damage, petechial rash, hemorrhaging, increased vascular permeability, and capillary leak syndrome. DSS is characterized by the DHF symptoms as well as dangerously low blood pressure and shock, which may result in death if fluid volume is not promptly restored. DHF and DSS have mortality rates of up to 30%.

Emergence of DHF and DSS

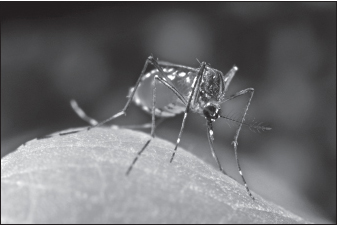

Dengue fever has been known in tropical areas of the world since 1770, with increasing numbers of epidemics occurring over time as the disease spread throughout Asia, Africa, and the Americas. The incidence of DHF and DSS are rapidly increasing as well. Dengue is now pandemic, due in part to events beginning during World War II when large-scale movement of vehicles and infected personnel, trapping of water in tires, and increased numbers of water storage areas brought the virus into areas with many new, susceptible human hosts and provided breeding habitat for the principal vector, Aedes aegypti, a day-biting mosquito whose preferential hosts are humans. Although A. aegypti numbers were once greatly reduced in much of the Americas due to large-scale mosquito elimination programs, vector numbers rebounded when the programs were halted during the 1970s. An additional mosquito vector, A. albopictus, is able to survive colder temperatures, including those found in many U.S. states.

Infection

Dengue virus is a single-stranded RNA member of the flavivirus group and is closely related to the causative agents of yellow fever and Japanese encephalitis. Four viral serotypes exist that are currently expanding their ranges. Several serotypes coexist in many parts of the world, triggering increasing numbers of DHF and DSS, as these disease manifestations usually occur following an individual’s secondary infection with a serotype differing from that first encountered. Host factors that affect disease severity include age, sex, and racial background: DHF and DSS are more common in female children and less common in those of African origin or persons suffering from malnutrition. Secondary infection with viruses of the DEN-2 serotype or strains originating in Asia is more likely to cause severe disease.

Immune Response

The immune response to dengue virus either may be protective or may increase pathology. DHF and DSS often result from antibody-dependent enhancement, a process in which nonneutralizing antibodies to one viral serotype decrease to low levels at the time of infection with dengue viruses of a different serotype. Low levels of these cross-reacting IgG antibodies lead to the formation of large immune complexes that are ingested by macrophages; these cells then act as hosts for replicating viruses. Inflammatory cytokines released by immune cells cause much of the pathology associated with infection, including increased vascular permeability, loss of fluid from capillaries, and destruction of platelets. Other cytokines, such as IFN-γ, may have dual roles during the illness, blocking viral replication but also increasing infection of macrophages. One viral protein blocks cellular responses to interferons in an attempt to evade the immune response.

Dengue fever (DF) and its more serious correlates, dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS), are currently found throughout the world, causing great pain and many deaths. It is the most common vectorborne infection of humanity, with 50 to 100 million cases of DF reported per year, mostly in tropical regions. Several hundred thousand cases of DHF occur as well, with a fatality rate of 5% in treated individuals. This severe condition is most common in children and young adults. Over time, the epidemics have become larger and more frequent due to population increases in urban centers and to rapid dissemination via air travel. The largest single epidemic involved 370,000 cases in Vietnam in 1987. In addition to the toll in human suffering and lives, dengue heavily taxes economic systems, often in regions that can ill afford this burden. The costs of medical intervention, mosquito eradication programs, and lost tourist revenues place a great strain on developing regions and health care systems already struggling under a host of other infectious diseases.

We are currently in the midst of a dengue pandemic as DHF spreads to countries in which it was previously unknown. In 1980, DHF was not endemic in any country in the Americas. By 1995, some 250,000 confirmed cases of DF and 7,000 cases of DHF were reported spread among 18 countries in the Americas. Dengue remains relatively rare are in United States, although over 400 confirmed cases have been brought into the country by travelers. This situation is likely to change, however, as the correct mosquito vectors are present in the United States. At least three cases are known to have been transmitted endogenously in Texas since 1980.

Four serotypes of the dengue virus have been reported from various locales around the globe. Each of these serotypes contains multiple viral strains that differ in virulence and in antigenicity. Areas of hyperendemicity (where more than one strain of dengue is endemic) are increasing, complicating epidemiological studies.

The first epidemics of dengue fever were reported in 1770 in Asia, Africa, and North America. Infections thereafter were periodic and infrequent, and intervals of 10 to 40 years often separated epidemics due to their slow spread by sailing vessels. Since the early 1980s, however, dengue has been at pandemic levels, its rapid spread fueled by an expansion of the geographical range of both the mosquito vector and all of the virus serotypes. Hyperendemicity is growing as multiple serotypes occupy the same region, resulting in the emergence of the more deadly manifestations of infection, dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome.

The modern DF pandemic began in Southeast Asia during the Second World War as a result of the movement of military equipment that trapped rainwater and led to the spread of the mosquito vector to previously uninfected regions. During the war, many water systems were destroyed and the number of water storage facilities increased, providing new niches for mosquito larvae to exploit. The outbreak was further spurred by the transit of hundreds of thousands of uninfected Japanese and Allied soldiers into infected areas. Mosquito hosts moved into most of the central and southern islands of the Pacific, although their isolation and small human populations kept dengue epidemics brief. Larger Pacific islands were also affected, and in 1953 and 1954, an epidemic of DHF occurred in Manila in the Philippines, having previously appeared in Bangkok, Thailand, in 1950. Earlier clinical reports of illnesses similar to DHF and DSS appear in medical records from northeastern Australia in 1897 and Greece in 1928.

Several decades after World War II, DHF again struck Asia in Sri Lanka, India, Pakistan, Taiwan, China, and Singapore as the range of the virus and its mosquito vector spread. Multiple serotypes were present during this epidemic, with the DEN-3 serotype predominating. The responsible viral strain was distinct from previous isolates. By 1975, DHF was the leading cause of hospitalization and death in children. About 900,000 cases of DHF and DSS occurred in Thailand between the years of 1958 and 1990. Since then, the incidence of dengue diseases in Southeast Asia has continued to increase in intensity as the presence of multiple viral serotypes in a given area became more frequent. Four times as many cases of DHF were reported in the past 15 years than were reported during the previous 30 years.

In Africa, dengue-related disease is also increasing. The surveillance system in the area is imperfect, but the number of DF epidemics has been rising since 1980, most notably in East Africa (Kenya, Mozambique, Sudan, Djibouti, and Somalia) and in Saudi Arabia. All four serotypes are active in these regions. Although sporadic cases of DHF have been reported in several of these countries, no epidemic of severe disease has occurred. In western Africa and parts of Southeast Asia, dengue virus also circulates in monkey populations.

Dengue was unknown in the Western Hemisphere until the advent of European colonization and the African slave trade. In the Americas, programs directed by the Pan-American Health Organization wiped out the mosquito vector, virtually eliminating yellow fever and decreasing the incidence of dengue until only sporadic cases of DF occurred in island areas that failed to eradicate the vector entirely. During the 1970s, these mosquito control programs were abandoned; as a result, the incidence of DF is now greater than before the vector control program began. In 1970, the DEN-2 and DEN-3 serotypes were found in the Americas, and the latter caused several epidemics in Puerto Rico and Colombia in the mid-1970s. DEN-1 was introduced into the area in 1977, resulting in epidemics of DF in Jamaica, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela in 1977 and 1978 before spreading throughout the Caribbean, north into Mexico and Texas, and south into Central America and northern South America. DEN-4 was imported into the eastern Caribbean in 1981 and caused major epidemics throughout the surrounding areas. The same year, a new strain of DEN-2 originating in Southeast Asia (most likely in Vietnam) was imported into Cuba, leading to the first major epidemic of DHF in the Americas. Over 10,000 cases of DHF occurred during this outbreak; however, large-scale hospitalization and effective fluid replacement therapy limited the number of deaths to 158 people. The next major epidemic of DHF began in Venezuela in 1989 and 1990, resulting in more than 6,000 cases of disease and 73 deaths. Between 1990 and 1995, DEN-2 led to a series of smaller epidemics in Colombia, Brazil, Puerto Rico, and Mexico. By 1997, 18 countries in the region had reported DHF cases. A novel strain of DEN-3 from Sri Lanka appeared in 1994 and led to an outbreak of DF in Costa Rica and Panama and DHF in Nicaragua. Yellow fever incidence has increased in the tropical areas of the Americas as well.

The United States has seen a small number of imported cases of dengue in Texas in 1980, 1986, 1995, and 1997. Although the virus has not yet established a foothold in the country, the United States is home to two species of suitable mosquito vectors, most notably Aedes aegypti, which abides in the Gulf Coast states from Texas to Florida. The other potential vector species, Aedes albopictus, entered the United States in the early 1980s and has spread to 25 states.

Several factors account for the spread of dengue. Numbers of mosquito vectors rise as the extent of urbanization in a region increases and adequate access to sewage treatment facilities decreases. The presence of pools of standing water also fuels the growth of mosquito populations. Aggressive vector control programs eliminated many of the dengue vectors from most of Latin America during the 1940s and 1950s, but subsequent increases in urbanization led to reinfestation of many areas during the 1970s. Air travel has also rapidly spread the virus to new locales with susceptible hosts. Between 1983 and 1995, the number of international travelers leaving the United States increased from 20 million to 40 million. Half of these people were bound for tropical regions.

The name dengue is derived from the Swahili ki denga pepo, which means “seizure caused by an evil spirit.”

The illness may manifest itself in three different forms: dengue fever, dengue hemorrhagic fever, or dengue shock syndrome. All forms may present with generalized vascular damage. Diffuse hemorrhage, edema, and congestion of organs also occur in DHF and DSS. In these two serious disease manifestations, antibodies produced in response to a prior infection may lead to the formation of large immune complexes containing antibody bound to microbial components, leading to the production of disseminated intravascular coagulation or hemorrhagic lesions with potentially lethal results.

Dengue Fever (DF)

Dengue fever, also known as breakbone fever, generally occurs in older children and adults. Infection may be asymptomatic or result in painful but short-term illness. After an incubation period of 3 to 14 days (usually 4 to 7 days), an infected person may present with fever of sudden onset, severe frontal headache, myalgia, and loss of appetite. This is followed by decreased numbers of neutrophils and platelets; severe eye, bone, and muscle pain; change in taste perception; nausea and vomiting; rapid heartbeat; and anxiety and depression. The extreme pain has been equated to that resulting from a multitude of broken bones. Later during the course of the infection, petechial rashes may be found on the extremities, underarms, and mucous membranes as a result of hemorrhaging of small blood vessels in the skin. This might be due to a host antibody response to the virus. Acute illness persists for eight to ten days. The infection is self-limiting and, though very painful, is seldom fatal in this form and is mild in comparison to DHF or DSS. Following treatment for DF, persons generally recover completely with the exception of some postinfection fatigue and depression. In rare cases, DF progresses to the more serious DHF or DSS.

Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF) and Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS)

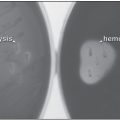

DHF and DSS constitute the severe dengue virus–associated diseases. More than 500,000 cases of DHF and DSS occur each year, with fatality rates ranging from 1% to 10%. If untreated, these rates may approach 30%. DHF and DSS are generally confined to children under the age of 15 years, with a fatality rate of up to 8%. Early disease manifestations include upper respiratory symptoms, anorexia, vomiting, and facial flush. Worsening of disease is accompanied by the onset of weakness, severe restlessness, facial pallor, profound abdominal pain, cyanosis (bluish hue to the skin), liver enlargement and damage, petechial rash, and bleeding gums. Serious pathology is linked to hemorrhaging two to six days after the onset of fever. Increased vascular permeability with capillary leak syndrome and fluid loss from the circulatory system, low white blood cell and platelet numbers, elevations in hematocrit of over 20%, and hemoconcentration accompany DHF. Decreased platelet levels may interfere with blood clotting, contributing to hemorrhaging. Large decreases in blood pressure, shock, and death may rapidly occur if the loss of plasma is not corrected and quickly countered by fluid replacement. Spontaneous hemorrhaging may be fatal if occurring in the gastrointestinal tract or the inner cerebral region of the brain.

DSS may occur as a result of a decrease in blood pressure and hemoconcentration as plasma leaks from the circulatory system into the tissues. It may present as a weak, rapid pulse; narrow pulse pressure (difference in systolic and diastolic pressures); hypotension; cold, clammy skin; and restlessness. DSS occurs in one-third of severe dengue cases and is most commonly seen in children. Platelet numbers are low, and bleeding times are prolonged. Major bleeding may occur from several sites on the body with or without the presence of shock. Treatment may include administration of intravenous fluids to increase blood volume and raise blood pressure to more optimal levels.

Factors Influencing the Development of DF Versus DHF or DSS

Several factors combine to determine whether a given individual infected with the dengue virus develops the relatively mild DF or the more severe DHF or DSS. Several of these factors relate to the immune system: antibody-dependent enhancement and the types of MHC molecules expressed on surface of the person’s cells (discussed later in this chapter). These factors increase the likelihood of developing severe disease in people who have a history of prior dengue infection after secondary infection with viruses of a different serotype than the original virus.

Table 15.1 Factors influencing the development of DHF and DSS

| Immune factors |