Overview

Delirium is a dangerous diagnosis. It is common; it is commonly missed; and it is associated with several adverse outcomes. Although most clinicians label patients with delirium as having an ‘acute change in mental status’, the formal diagnostic criteria according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-Text Revision) paints a more complete and descriptive picture of these patients if put into sentence form: ‘A sudden onset of impaired attention, disorganized thinking or incoherent speech. The patient usually has a clouded consciousness, perceptual disturbances, sleep–wake cycle problems, psychomotor agitation or lethargy and is disoriented’.1

History and Pathophysiology

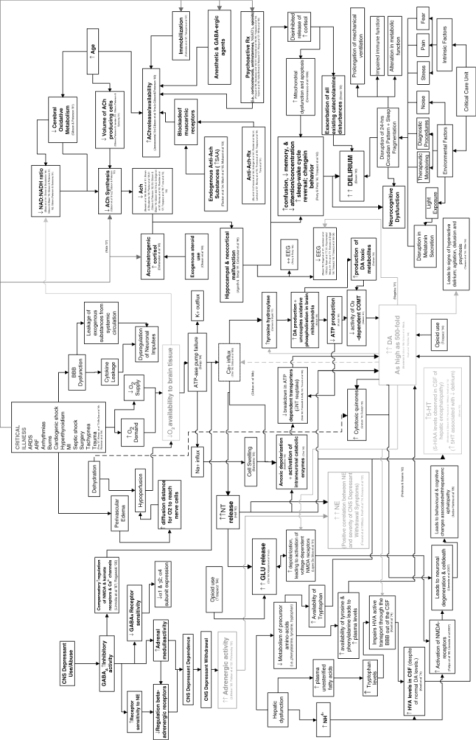

Although the term ‘delirium’ was not used, references to patients with delirium date as far back as the time of Hippocrates. Delirium has only attracted attention as a syndrome or a diagnosis in the past three decades, with the first textbook dedicated solely to delirium being published in 1980.2 The reasons for this long misunderstanding of what to call this constellation of symptoms are related to the various ways in which delirium can present (hypoactive, hyperactive or a combination of the two) and the complex pathophysiology that causes such a variety of presentations. Although research into the pathophysiology of delirium is in its infancy in clearly defining the contribution each neurotransmitter system and biochemical mechanism has on the clinical picture of delirium, one proposed pathoaetiological model of delirium (Figure 71.1) is important in helping clinicians understand the complexity of a patient with delirium.3 By keeping the complex systems and mechanisms in mind when trying to diagnose or manage a patient with delirium, clinicians will better be able to understand the challenges in making an accurate diagnosis (especially in the face of dementia) and the significant limitations that medications have in the ‘treatment’ of delirium.

Figure 71.1 The pathoetiological model of delirium. Reprinted from Maldonado JR (2008).3 Copyright (2008), with permission from Elsevier. A high-resolution version of this figure is available at Wiley Book Support homepage, http://booksupport.wiley.com.

Prevalence and Incidence for Various Sites and Situations

Delirium is one of the most serious illnesses that patients can have or develop and one that clinicians should not miss at the reported rate of 32–66%.4 Typical rates of delirium on admission to a medical unit are between 20 and 30%. In a thorough systematic review of 42 studies meeting selection criteria with a focus on medical inpatient settings, only eight performed delirium assessment within 24 h of admission. The prevalence of delirium on admission among these well-performed studies ranged from 10 to 31%, but the low 10% was thought to be an underestimate as this study had strict selection criteria. In the same systematic review, the incidence during hospitalization among 13 studies was 3–29%.5

In general, surgical patients have been found to have higher rates of delirium than medical patients. In a review of primary data-collection studies, Dyer et al. found that rates are highest postoperatively among coronary artery bypass graft patients, ranging from 17 to 74% (>50% in five of the 14 studies reviewed).6 They also found that rates among orthopaedic surgical patients ranged from 28 to 53% (>40% in five of the six studies). Of the two urological studies reviewed, rates ranged from 4.5 to 6.8%. Past biases have blamed anaesthesia agents for most cases, which wrongly have kept alive the belief, like that in the case of the intensive care unit (ICU), that delirium is unpreventable. Several studies which have evaluated the association between routes of anaesthesia (general, epidural, spinal, regional) and the risk of postoperative delirium have found that the route of anaesthesia was not associated with the development of delirium.

One of the sites with the highest rates of delirium, but perhaps the most controversial because of so many complicating factors, is the ICU. Rates as low as 19% and as high as 80% have been found.7, 8 For years, however, people have ignored these facts, have called it inevitable and unpreventable and have even labelled it ‘ICU psychosis’ so as to blame it on the ICU.

Discharge or ‘transition’ of patients out of the acute hospital setting has seen many changes over the past three decades. Data from post-acute care facilities (under such names as subacute-care facilities, skilled nursing facilities, rehabilitation centres and long-term care facilities) reveal two major issues: patients are discharged from acute hospitals with persistent delirium and delirium at these sites persists for an extended period of time. Kelly et al. found that 72% of 214 nursing home patients who were hospitalized for delirium still had delirium at the time of discharge back to the nursing home. The delirium persisted for 55% of the patients at 1 month and 25% at 3 months after discharge.9 Marcantonio et al. found that 39% of 52 patients with hip fractures were discharged with delirium, which persisted for 32% of the patients at 1 month and 6% at 6 months after discharge.10 In a large study of over 80 post-acute care facilities using the Minimum Data Set (MDS) to identify patients with any symptoms of delirium, Marcantonio et al. found a prevalence rate of 23% on admission. Among these patients, 52% still had the symptoms at 1 week follow-up.11

Two studies that looked at point of prevalence within nursing facilities discovered a similarly high rate of delirium. Mentes et al. evaluated 324 long-term nursing home residents using the MDS and found that 14% of patients had delirium.12 Cacchione et al. prospectively evaluated 74 long-term nursing home patients and identified 24 (33%) with delirium.13 While neither study could determine whether the delirium was a persistent one after a hospital stay or was an incident (new episode of) delirium, it is evident that delirium is common among nursing home residents.

Home care is an understudied site concerning delirium. However, two studies (detailed in the section ‘Prevention and management interventions’) showed lower rates of delirium among ill, older persons cared for at home compared with similarly ill, older persons cared for in the hospital. It is unclear whether something positive is being done in the home that prevents delirium or whether something negative is occurring in the hospital that contributes to the development of delirium.14, 15

Associated Adverse Outcomes

Data about the adverse outcomes associated with delirium mainly come from studies of older patients in the hospital setting. Here, delirium has been found to be associated with hospital complications, loss of physical function, increased length of stay in the hospital, increased instances of discharge to a long-term care facilities and high mortality rates. Mortality rates for hospitalized delirious patients have been reported to be 25–33%, as high as the mortality rates for acute myocardial infarction and sepsis. There has been some question in the past about whether delirium was independently associated with these adverse outcomes or whether it was merely a marker of severe illness and physical frailty, since most studies identified older age, underlying cognitive impairment, severe, acute and chronic illness and functional impairment as the predisposing factors. However, when adjusting for these factors, delirium has been found to be independently associated with poor outcomes in most studies.

Associated adverse outcomes among delirious ICU patients have shown prolonged ICU stay, prolonged hospital stay and increased mortality compared with patients without delirium.7, 8 Data from post-acute facilities have also shown associated adverse outcomes, related to loss of physical function and mortality.9, 11, 13

The Comprehensive Approach to Delirium

In order to improve the adverse outcomes associated with delirium, it is not enough just to improve our skills in diagnosing delirium and treating the underlying medical causes. The following are the necessary components of a comprehensive approach for those involved in the care of older persons and healthcare systems that interface with older persons:

Although there are no available studies to date that implement all five interventions, a multifaceted approach is warranted because of the nature of this multifactorial problem.

Awareness

Delirium should become part of the medical jargon for all who care for older persons. Furthermore, given the frequency with which delirium is seen and the seriousness of this diagnosis, a vital sign for mental status has been recommended,16 and rates of incidence and outcomes associated with delirium could be considered as quality-of-care measures.

Diagnosis

Delirium is not dementia. There is no difference in the core features of delirium in the DSM-IV-TR version compared with the previous version, DSM-IV, except that the DSM-IV-TR version recognizes that delirium can arise during the course of dementia.1 Although this appears to be a minor detail, the message that this gives to healthcare professionals is a critically important one: ‘delirium is not dementia’. Most types of dementia have a progressive downhill course. Delirium should be considered reversible. A mislabelling or lack of differentiation between these two diagnoses is thought to be the reason why delirium is missed by physicians and by nurses. Misdiagnosis or late diagnosis may also partly explain why delirium is associated with adverse outcomes. Table 71.1 details some of the differentiating characteristics between delirium and dementia, based on DSM criteria, keeping in mind that one of the criteria not in Table 71.1 is that delirium must occur in the context of a medical illness, metabolic derangement, drug toxicity or withdrawal.

Table 71.1 Differentiating delirium from dementia.

| Delirium | Dementia | |

| Consciousness | Decreased or hyper-alert | Alert |

| ‘Clouded’ | ||

| Orientation | Disorganized | Disoriented |

| Course | Fluctuating | Steady, slow decline |

| Onset | Acute or subacute | Chronic |

| Attention | Impaired | Usually normal |

| Psychomotor | Agitated or lethargic | Usually normal |

| Hallucinations | Perceptual disturbances | Usually not present |

| May have hallucinations | ||

| Sleep–wake cycle | Abnormal | Usually normal |

| Speech | Slow, incoherent | Aphasic, anomic, difficulty finding words |

Altered level of consciousness (LOC) is an excellent clue in differentiating delirium and dementia because it is not always possible to know the patient’s baseline mental status. Without ever having seen the patient before, one can determine whether the patient’s LOC lies towards the agitated or vigilant side of the spectrum of LOC or towards the lethargic, drowsy or stuporous side of the spectrum.

One can ask orientation questions, but since disorientation and problems with memory are present in both delirium and dementia, the key in determining delirium from dementia is how the patient answers. The delirious patient will often give disorganized answers, which can be described as rambling or even incoherent.

The classic identifiers of delirium are acute onset and fluctuating course, both of which are usually obtained by close caregivers (family or nurses). Although acute implies 24 h, the term subacute is used to emphasize that subtle mental status changes can be overlooked by caregivers. Over a period of many days, the patient may appear to be slowly declining mentally due to the underlying dementia. If left unchecked, the initial delirium may impair other necessary functions, leading to further medical problems, such as dehydration and malnutrition, further complicating the delirium. This snowball effect explains in part why the aetiology of delirium is typically multifactorial. Therefore, if it is unclear how long the change has been occurring, patients should be put in the category of delirium and an evaluation should be made.

Attention is also one of the classic identifiers of delirium, which may often be helpful if the patient’s baseline mental status is not known. It can be tested by having a conversation. Patients may have difficulty maintaining or following the conversation, perseverate on the previous question or become easily distracted. Attention can also be tested with cognitive tasks such as days of the week backwards, spelling backwards or digit span.

Psychomotor agitation or lethargy, hallucinations, sleep–wake cycle abnormalities and slow or incoherent speech can all be seen in patients with delirium, but these features are not necessary for the diagnosis.

Evaluation

General guidelines for the medical evaluation of patients are to consider all possible causes, proceed cautiously with appropriate testing and keep in mind that delirium is usually caused by a combination of underlying causes.

After a physical check and ascertaining the history, which includes obtaining details from anyone considered a caregiver (e.g. family, nurse’s aide) and a thorough medication list, the mnemonic D-E-L-I-R-I-U-M-S can be used as a checklist to cover most causes of delirium (Table 71.2). Drugs are notorious for causing delirium. According to most authors in this area, ‘virtually any’ and ‘practically every’ drug can be considered deliriogenic. Several drugs have been found in vitro to have varying amounts of anticholinergic properties. However, since the pathophysiological and neurotransmitter mechanisms of delirium go beyond anticholinergic mechanisms, a more practical approach is to remember certain categories of medications that have been reported to cause delirium, some more common than others. The mnemonic A-C-U-T-E C-H-A-N-G-E I-N M-S is long, as would be expected, but highlights why drugs are such a common cause of delirium (Table 71.3). In order to be as inclusive as possible and because many older reports did not discuss strict delirium criteria or such criteria were not commonly used, the following paragraphs describe not just delirium as a side effect, but also psychiatric side effects that might indicate presence of delirium, such as hallucinosis, paranoia, delusions, psychosis, general confusion, aggressiveness, restlessness and drowsiness.17

Table 71.2 Causes of delirium.

| D | Drugs |

| E | Eyes, ears |

| L | Low O2 state (MI, stroke, PE) |

| I | Infection |

| R | Retention (of urine or stool) |

| I | Ictal |

| U | Underhydration/undernutrition |

| M | Metabolic |

| (S) | Subdural |

Table 71.3 Medications that can cause (have been reported to cause) an A-C-U-T-E C-H-A-N-G-E I-N M-S (mental status).

| A | Antiparkinson drugs |

| C | Corticosteroids |

| U | Urinary incontinence drugs |

| T | Theophylline |

| E | Emptying drugs (e.g. metoclopramide, compazine) |

| C | Cardiovascular drugs |

| H | H2 blockers |

| A | Antibiotics |

| N | NSAIDs |

| G | Geropsychiatry drugs |

| E | ENT drugs |

| I | Insomnia drugs |

| N | Narcotics |

| M | Muscle relaxants |

| S | Seizure drugs |

Levodopa (an antiparkinson drug) has been reported to cause mental status changes at a rate of 10–60% and include hallucinosis on a background of a clear sensorium, delusional disorders and paranoia. Abnormal dreams and sleep disruption may precede the more frank delirium symptoms and may be an early clue to their onset. Selegiline has been reported to cause mental status changes described as psychosis, aggressiveness and even mania.

Corticosteroids have been reported to cause ‘psychiatric complications’ in up to 18% of patients with doses above 80 mg per day. The mental status changes seen have been described as depressive/manic, an organic affective disorder with associated paranoid-hallucinating features and general ‘confusion’.

Although short-acting urinary incontinence drugs have a greater potential to cause delirium, newer sustained release agents have also been reported.

Theophylline ‘madness’ probably meets delirium criteria. One of the first case reports described a patient with a toxic blood level that correlated with hyperactive periods marked by flailing of limbs, intense emotional lability, incessant crying and ripping out of intravenous lines and nasogastric tubes.

‘Emptying’ drugs is a reminder that drugs such as metoclopramide and droperidol that are often used for nausea and vomiting have potential for mental status changes. Reported mental status side effects include restlessness, drowsiness, depression and confusion. The mechanism is likely because of their antidopaminergic properties.

Cardiovascular drugs rarely cause mental status problems, but because they are so commonly prescribed for older persons, it is worthwhile to remember that some are more likely to cause problems, and also a few that have been reported in case reports. One of the first reports of confusion due to digoxin toxicity was over 100 years ago. Since then, reports of confusion even at therapeutic levels have been published. Antihypertensive agents that may cause mental status changes have primarily been reported in the literature through case reports. However, since they are so commonly used, it is worthwhile being suspicious about a few of them. These include beta-blockers (including in the form of eye drops), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium channel antagonists.

H2 blockers, because they are primarily renally excreted and may have some H1 activity (antihistamine receptor subtype-1), may cause delirium, especially if patients have underlying risk factors such as renal insufficiency and dementia.

Antimicrobials, like cardiovascular drugs, rarely cause mental status changes, but are very commonly used; some examples worth being aware of are penicillin, erythromycin, clarithromycin, gentamycin, tobramycin, streptomycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, some cephalosporins and the antiviral acyclovir, particularly at high doses. Most reports propose that the mechanisms by which antimicrobials cause mental status changes are related to impaired renal function, drug–drug interaction and occasionally idiosyncratic behaviour. Several types of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been reported to cause delirium, even the selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree