Improvements in radiographic imaging over the last several decades have led to an increased recognition of cystic lesions in the liver and biliary tract. These cysts have a wide range of etiologies including congenital malformations, infections, and neoplasms. This chapter discusses benign, infectious, and neoplastic cysts of the liver and biliary tract. A complete understanding of the presentation, risk factors, and radiologic features is crucial to accurately identifying these cysts. Accurate identification is essential for determining the best treatment strategy, which may require surgery.

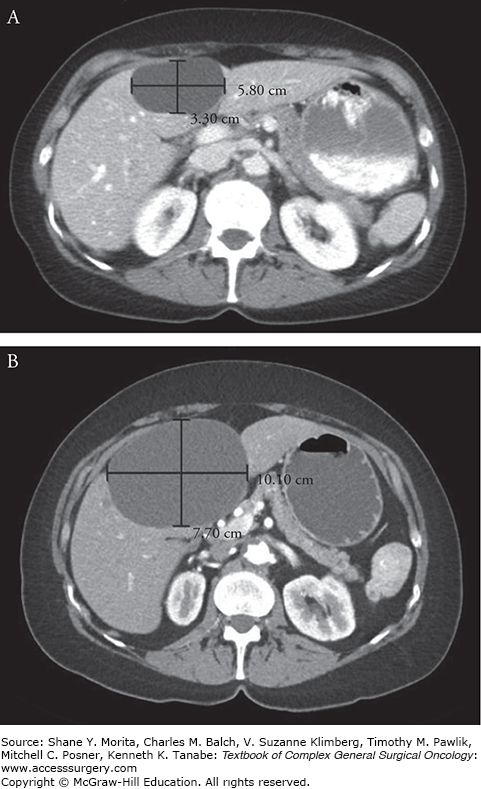

Simple cysts of the liver are spherical or ovoid cystic formations without septations containing serous fluid which are lined by a single layer of biliary columnar or cuboid epithelial cells. These cysts are congenital, having originated from aberrant bile ducts that have lost communication with the biliary tree and as a result have no direct communication with the bile ducts.1 Despite a biliary origin, these cysts rarely contain bile. The majority of patients will have a solitary cyst, although multiple cysts can be seen. The cells lining the cyst continue to secrete serous intraluminal fluid and as a result the cyst may gradually increase in size, although few will grow large enough to be symptomatic (Fig. 137-1). While most are less than 3 cm, rare hepatic cysts have been reported over 20 cm in diameter.2 Simple cysts can be found in any part of the liver but are more commonly located in the right lobe (Fig. 137-2).3

Noninfectious simple liver cysts are a frequent incidental finding in asymptomatic adults undergoing workup by ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) for other purposes. Simple hepatic cysts have been reported in 2.5% to 18% of adult patients without prior liver disease who have undergone abdominal imaging by ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).3–5 Cysts are more prevalent in older females; large, symptomatic cysts are found almost exclusively in females.3 While most patients with simple cysts are asymptomatic, symptoms may occur due to enlargement, mass effect, infection, hemorrhage, or rupture of the cyst. Patients with simple cysts may present with abdominal discomfort, pain, nausea, or early satiety often related to the size or location of the cyst. Simple cysts greater than 4 cm in diameter and those located in the right lobe of the liver are more likely to be symptomatic. In addition, larger cysts are more prone to complications such as rupture or spontaneous hemorrhage which are usually symptomatic.

Abdominal imaging with ultrasound, CT, or MRI is useful for the identification of simple cysts. Ultrasound is the most accurate imaging modality to confirm the diagnosis and differentiate simple cysts from other hepatic lesions, and in many cases further images is not necessary. On ultrasound, simple cysts appear as a circular or oval, unilocular anechoic lesion with a smooth, imperceptible wall and posterior acoustic enhancement.2 In situations involving intracystic hemorrhage, ultrasound will demonstrate a hyperechogenic pattern with internal echoes that mimic septations. On abdominal CT, simple cysts appear as a round, well-defined hypoattenuating, homogenous lesion without enhancement of the wall following contrast administration.6,7 MRI may be useful for diagnosis in difficult cases, and cysts will be characterized on T1-weighted images as hypointense, homogeneous lesions with a high-intensity signal without contrast enhancement on T2-weighted images.8 All three imaging modalities are complementary, but all are seldom needed for diagnosis. Aspiration of the fluid is rarely necessary to make a diagnosis, but when performed the fluid is sterile with negative cytopathology.

Most simple cysts of the liver will not require treatment. Asymptomatic cysts are managed conservatively, with regular imaging by ultrasound recommended for cysts greater than 4 cm to monitor for stability. Cysts that rapidly increase in size should be thoroughly worked up to rule out an underlying malignancy, as simple cysts generally remain stable in size. Symptomatic patients will often require intervention with sclerotherapy or surgical resection to alleviate symptoms for large cysts. Sclerotherapy involves destruction of the epithelial lining of the cyst in order to disrupt intraluminal fluid secretion. A drainage catheter is placed by image guidance, and a sclerosing agent such as ethanol, ethanolamine oleate, or minocycline hydrochloride is injected and allowed to instill before removal.9 Simple aspiration of fluid without sclerotherapy is not advisable, given the high likelihood of fluid reaccumulation, and some advocate reserving sclerotherapy for those patients not eligible for surgery, given high recurrence rates.10 In addition, sclerotherapy is contraindicated in patients with a fistulous tract between the cyst and biliary tree or intracystic bleeding.

In the past, surgical treatment of simple cysts involved complete excision in order to prevent recurrence. However, given high complication rates this was abandoned in favor of surgical fenestration, or “unroofing,” which involves removal of the roof of the cyst to allow for free drainage into the abdominal cavity. Compared with more radical procedures such as hepatic resection, lobectomy, or complete cyst excision, fenestration is associated with a lower risk of morbidity and mortality.11 Operative series for laparoscopic fenestration has demonstrated a mortality rate of 0%, a major complication rate of only 6.3%, and a reoperation rate of 9%.12 Laparoscopy has become the primary approach for surgical therapy given its association with reduced hospital stays, decreased complication rates, and reduced postoperative pain. Recent analysis shows the overall recurrence rate for surgical fenestration is 11.1%, with a lower rate by the laparoscopic approach compared with laparotomy (6.1% vs. 11.5%, respectively).13 Additionally, recurrence rates for laparoscopy have steadily declined as surgical technique has improved, with earlier recurrences attributed to inadequate unroofing of the cyst.13 Laparoscopic cyst fenestrations can be performed safely and effectively in all hepatic segments, but a potential limitation may be the difficulty in completely unroofing cysts located in the right posterior segments due to technical difficulties.

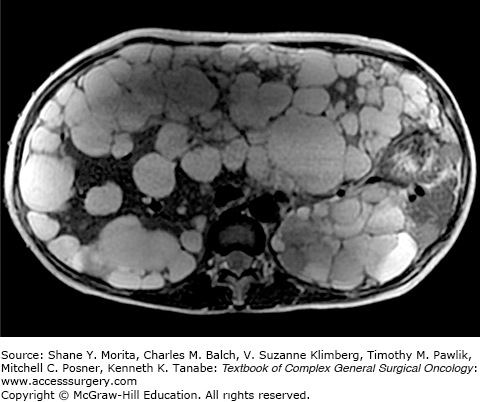

Polycystic liver disease (PCLD) is an autosomal dominant disorder resulting in the development of multiple hepatic cysts. Histologically, these cysts are similar to simple cysts of the liver, but are numerous and found in a wider distribution. In addition to the grossly visible macrocysts, numerous microscopic hepatic cysts are frequently present. The cysts are lined by a single-layer epithelium with the retained functional characteristics of biliary epithelium, including a secretory capacity. The cysts are due to a malformation and abnormal remodeling of the ductal plate during embryonic development leading to dilated biliary microhamartomas, known as von Meyenburg complexes, that have lost communication with the biliary tree.14,15 Despite the presence of multiple, large cysts, liver function is usually preserved.

Polycystic liver disease is most often seen in patients with adult dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD), although studies have demonstrated PCLD in patients without ADPKD. Both, however, have similar clinical courses and are autosomal dominant. PCLD associated with ADPKD is due to mutations in either the PKD1 (polycystin 1) or PKD2 (polycystin 2) gene, with PKD1 accounting for the majority of mutations in ADPKD patients.16 Polycystin 1 and polycystin 2 interact to mediate cell–cell adhesions in ciliated cells of the liver and kidney, and mutations in these proteins lead to the development of renal cysts, renal failure, and liver cysts. Alternatively, isolated autosomal dominant PCLD without an association with ADPKD is rare, with an incidence of less than 0.01% in the general population. This form of PCLD is due to mutations in either protein kinase C substrate 80K-H (PRKCSH) or SEC63 genes.17 Both genes are important for proper functioning of the endoplasmic reticulum in cholangiocytes. PRKCSH encodes a protein, hepatocystin, which is involved in protein folding and quality control of synthesized glycoproteins. SEC63 encodes the SEC63 protein which is involved in transport of proteins across the endoplasmic reticulum. Despite these findings, PRKCSH and SEC63 do not cause all cases of PCLD and other genes are believed to be involved.

Adult dominant polycystic kidney disease is a common human renal disorder with a reported prevalence of 1:400 to 1:1000 patients.18 The prevalence of PCLD in patients with ADPKD ranges from 20% to over 75%, and renal cyst formation always precedes the development of hepatic cysts.15,19 Alternatively, isolated PCLD without ADPKD is rare. Overall, the prevalence of PCLD increases with age. Hepatic cysts are rarely seen in patients younger than 20 years old, and 80% of patients with PCLD will be over 60 years old. PCLD occurs in both sexes, although women with PCLD due to ADPKD tend to have larger size and number of cysts. In addition, advanced age, pregnancy, and female gender are all noted to be risk factors for cyst growth and increasing liver involvement.

Patients with PCLD are usually asymptomatic, especially those with few number of cysts or smaller sized cysts. Symptoms often develop due to an increase in cyst size or number, leading to abdominal pain, discomfort, early satiety, and shortness of breath. Complications are uncommon but include infection, rupture, and hemorrhage into a cyst. Hepatomegaly is often noted upon physical examination. Hepatic parenchyma is usually preserved and no signs of liver failure are present, so liver function tests (LFTs) are almost always normal. Imaging is useful to determine the size and number of cysts in addition to their relationship with nearby structures (Fig. 137-3). On ultrasound, multiple anechoic, round, fluid-filled cysts with clear margins and no septations are seen in the liver. Abdominal CT scan is often the most useful imaging modality and will demonstrate nonenhancing cysts that are distinct from the surrounding hepatic parenchyma. Cysts that have irregularly thickened walls, septations, or changes in attenuation are suspicious for complications such as bleeding or neoplasm. On MRI, cysts are hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. A hyperintense signal on T1-weighted image should be concerning for hemorrhage into the cyst.

Definitive treatment for PCLD is difficult and depends on the number, size, and location of cysts. As such, it is usually reserved for symptomatic patients. Patients with a few large cysts greater than 5 cm in size causing symptoms such as pain may undergo percutaneous aspiration and sclerotherapy with ethanol, tetracycline, or ethanolamine oleate. Most patients who undergo this method of treatment have improved symptoms, but usually recur. Furthermore, this method is not commonly used as most patients have symptoms due to multiple cysts. Similarly, hepatic resection is possible in patients where the symptomatic cysts are predominately isolated to one region of the liver, but this is uncommon. Fenestration of the cyst by an open or laparoscopic approach has been described for symptomatic patients with cysts in close proximity, but has had limited success given a recurrence rate for symptoms of almost 50%.20 The only definitive treatment for patients with severe, symptomatic PCLD is orthotopic liver transplantation.21 Patients with renal failure due to polycystic kidney disease should also be considered for a combined liver and kidney transplant.22,23

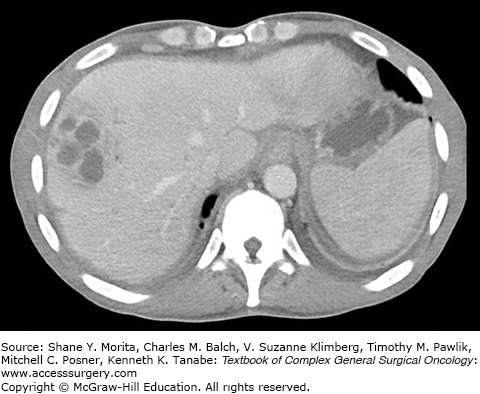

Pyogenic liver abscesses are solitary or multiple pus-filled collections inside of the liver resulting from a bacterial infection (Fig. 137-4). Earliest reviews on hepatic abscesses noted a prevalence in young patients due to acute appendicitis as a result of portal venous drainage that allowed bacteria to travel to the liver from sites of underlying gastrointestinal infection.24 With the advent of antibiotics, hepatobiliary and pancreatic sources have replaced intra-abdominal infection as the common cause of pyogenic liver abscesses. Most hepatic abscesses are polymicrobial containing both enteric aerobic and anaerobic bacteria, and the most frequently cultured bacteria include Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus viridans, Enterococcus species, and Bacteroides species.25,26 Additionally, Candida species has been found in cultures isolated from liver abscesses in as many as 22% of patients.26 Pyogenic hepatic abscesses are rare, with the current annual incidence estimated at 3.6 cases per 100,000 population in the United States, a number that has not drastically changed over time.24,27 Bacterial abscesses of the liver are most commonly seen in patients over the age of 50 years with a slight predominance in males, diabetics, and patients with underlying liver or pancreatic disease.26–28 The majority of pyogenic abscesses involve the right liver, and bilobar disease is less common.26 The most common symptoms at clinical presentation are fever and abdominal pain, but weight loss, nausea, vomiting, hepatomegaly, jaundice, and fatigue are also seen.26,29,30

Ultrasound and CT scan are the most commonly used imaging modalities for diagnosis. Ultrasound is often the first modality employed for diagnosis, given its ease of use and high sensitivity for diagnosis, and will show a round, smooth-walled hypoechoic lesion.31 CT scans have a sensitivity of up to 97% for diagnosis, and hepatic abscesses will appear as hypoattenuated areas with rim enhancement surrounded by edema.32 CT scans also have the advantage of simultaneously identifying any intra-abdominal pathology that may be the cause. MRI may be utilized for evaluation of the biliary tree, but its widespread use tends to be limited by cost. Intravenous antibiotics used in conjunction with percutaneous drainage techniques have become the mainstays of therapy.33 Patients with a suspected pyogenic liver abscess should be started on empiric, broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics to cover gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic organisms, with coverage narrowed based on the results of blood and abscess cultures. Antibiotics should be continued until symptoms such as fever and leukocytosis have resolved, often for at least two weeks after stabilizing clinically. Since the 1980s, percutaneous drainage by ultrasound or CT guidance has been used for diagnosis and treatment. Percutaneous drainage can be achieved either by complete aspiration of all purulent material or placement of a drain; most recommend drain placement with aspiration reserved for small, unilocular abscesses.34–36 Surgical therapy is rarely utilized anymore; it is limited to a few situations such as failure of percutaneous drainage due to a large, multiloculated abscess and abscess rupture into the abdomen necessitating washout; or surgery is required to treat the underlying etiology such as acute appendicitis or cholecystitis allowing for concomitant abscess drainage.33 With improvements in treatment, overall mortality in recent years has decreased and has been reported as low as 3%.33

Amebic liver abscesses are purulent collections in the liver caused by infection with Entamoeba histolytica, an invasive anaerobic parasitic protozoan. The highest incidence of amebic liver abscesses is in tropical countries such as Mexico, Central and South America, Africa, and India.37 While rare in the United States, it is predominantly seen in areas with immigrants from endemic areas. Amebic liver abscesses are predominantly seen in males despite an almost equal prevalence of intestinal amebiasis between genders, with a peak incidence in the third and fourth decades of life.38 Infection occurs when an individual ingests fecally contaminated food or water containing the cysts, which hatch or “excyst” in the digestive tract. The trophozoite then either remains dormant in the intestinal lumen or becomes virulent and invades the intestinal mucosa.37 Once invasion occurs, the trophozoite can spread extraintestinally through the blood stream, commonly to the liver. While as much as 12% of the world’s population is believed to be infected with intestinal amebiasis, only a small proportion of individuals will develop liver abscesses.37 Once in the liver, the trophozoite will cause liquefaction necrosis producing a cavity of liquefied liver tissue and blood, often resembling an “anchovy paste.”

Patients with an amebic abscess typically present with fever, abdominal pain, right upper quadrant tenderness, and hepatomegaly. Rupture of the abscess into the chest or abdominal cavity can occur, and patients may present with peritonitis. Rarely, patients will also have concurrent signs of amebic dysentery such as diarrhea over the proceeding weeks to months. An enzyme-linked immunosorbant assay (ELISA) to specific E. histolytica antibodies in the serum is reported at almost 100% and is the most useful laboratory evaluation for detection.39–41 Imaging is key to the diagnosis of an amebic liver abscess. CT scan is often the most useful and sensitive imaging modality, demonstrating a well-circumscribed liver lesion with an enhancing wall and surrounding edema.42 Ultrasound will show a round or oval lesion with decreased echogenicity compared to the surrounding liver parenchyma, although early lesions can be missed.43–45 MRI and chest radiographs may also be useful for diagnosis and characterization of the abscess. The gold standard for treatment of amebic liver abscesses are amebicidal drugs, primarily metronidazole dosed 750 mg orally three times a day or 500 mg intravenously every 6 hours for 7 to 10 days.46 Improvement is seen in most patients within 3 days, and metronidazole is curative in up to 90% of patients with hepatic abscesses. Other medications, such as emetine hydrochloride, nitazoxanide, and chloroquine phosphate, can be used if metronidazole is not available but are often less effective. Treatment of intestinal amebiasis with iodoquinol or paromomycinis is also recommended even if patients do not have stool cultures positive for cysts. Percutaneous catheter drainage and therapeutic aspiration can be used in patients in whom metronidazole is not effective, cannot be used such as in pregnancy, or when rupture is considered imminent. Surgical therapy is limited to those who fail conservative methods and those with complications, and open surgical drainage is often used to treat amebic abscess rupture into the pleural or peritoneal cavities.46 With treatment, the majority of patients will improve and overall mortality will be less than 5%.46

An echinococcal cyst, or hydatid cyst, of the liver is a rare parasitic disease caused by infection due to a tapeworm, Echinococcus granulosus. In the United States the incidence is less than one case per million inhabitants, but echinococcosis is highly endemic in the Mediterranean, parts of Europe, northern and eastern Africa, parts of South America, China, and Asia. In these regions where sheep farming is predominant, the prevalence may be as high as 5% to 10% of the population.47 In the United States, the disease is primarily encountered in immigrants from these regions or Americans who have traveled to highly endemic areas and ingest food contaminated with Echinococcus eggs. Hydatid disease of the liver is transmitted through a fecal-oral route.47,48 The definitive hosts of Echinococcus are carnivores such as canines which are infected through the consumption of the viscera of intermediate hosts. The adult tapeworm resides in the small intestine of a definitive host, releasing eggs that are passed into the feces. Intermediate hosts, usually herbivores and omnivores, become infected with Echinococcus by ingesting parasite eggs on the contaminated ground. The eggs hatch and release embryos, which penetrate the intestinal wall and enter into portal circulation where the embryos are able to infect any tissue such as the liver, lungs, or brain. Once the canine or other carnivore consumes the animal and its infected organ, the cycle begins again. Humans are accidental hosts in the lifecycle of the tapeworm, as they are unable to transmit the disease to other organisms.

The most common site of cyst formation in humans is the liver, accounting for up to 85% of all echinococcal infections.47 In the liver, a spherical, fluid-filled unilocular cyst forms which consists of an inner single-cell germinal layer containing the developing echinococcal protoscoleces that protrude into the cyst. Occasionally, daughter cysts will also form within the periphery of the cyst; however, the majority of patients have only a solitary cyst. The echinococcal cyst will slowly grow due to the accumulation of fluid, and over time will lead to symptoms. The clinical presentation is dependent on the size and location of the cyst. Small cysts are rarely symptomatic, with symptoms occurring due to mass effect on surrounding organs or blood vessels or rupture of the cyst. In addition, clinical manifestations rarely occur until adulthood. Typical symptoms at presentation include right upper quadrant pain, hepatomegaly with or without a palpable mass, fever, nausea, and vomiting.48 Cyst expansion may lead to rupture into the biliary tree or erosion through the diaphragm into the pleural cavity in as many as one-third of all patients, leading to symptoms of jaundice, biliary obstruction, cholangitis, or productive cough. Rarely, these cysts can rupture into the peritoneum, which leads to dissemination and an anaphylactic reaction.

Diagnosis relies on the combination of imaging and serological tests. Routine blood work may show normal or mildly elevated transaminases on LFTs with mild increases in the alkaline phosphatase or γ-glutamyl transferase (GGT). In addition, a complete blood count (CBC) with differential may show eosinophilia in between 15% and 60% of patients, but is only seen in those with leakage of cystic material or cyst rupture. Historically, serological tests involving indirect hemagglutination were used to confirm the diagnosis. However, this has been replaced by an ELISA to detect anti-Echinococcus antibodies with a sensitivity as high as 95% depending on the specific antigen preparation.49 In situations without a positive serologic test, percutaneous aspiration or biopsy under ultrasound or CT guidance may be used for diagnosis to demonstrate the presence of protosolices, hydatid membranes, or hooklets. However, this method is reserved for rare situations when other diagnostic methods are inconclusive, given the risk of complications including dissemination of disease and anaphylaxis.50,51 Imaging by ultrasound, CT, or MRI can be used to identify and diagnose echinococcal cysts. Ultrasound is the most commonly used modality, given it is noninvasive, easy to use, accessible, and cost-effective compared with other modalities. Ultrasound allows for the identification of cysts including defining the size, number, and location with a sensitivity and specificity upwards of 90% for diagnosis.52 Importantly, the major classification systems use ultrasound to classify echinococcal cysts into subtypes. The earliest classification system for echinococcal cysts was proposed by Gharbi et al53 in 1981 that divided cysts into five types based upon ultrasound findings.53 The World Health Organization (WHO) later developed a new classification system to stage hepatic hydatid cysts based upon ultrasound findings and the functional status of the parasite, with recommendations for management depending on the stage (Table 137-1).52 Similar to ultrasound, CT can provide not only information regarding cyst size and number, but also more detailed information on location, depth, and relationship to vascular structures, making it useful for surgical planning. On CT scans, echinococcal cysts appear as hypoattenuating lesions, and daughter cysts can be more clearly visualized compared to other imaging modalities. MRI can provide structural details about the hydatid cyst including the relationship with biliary and vascular structures.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree