CRYPTORCHIDISM

DEFINITION AND EMBRYOLOGY

Cryptorchidism, a term derived from the Greek cryptos (hidden) and orchis (testis), is defined as a developmental defect characterized by the failure of the testis to descend completely into the scrotum. The development of the gonads and genital duct system begins at approximately the fifth week of gestation. The gonadal primordia develop as a thickening on the medial aspect of the mesonephros, forming a bulge in the dorsal wall of the coelomic cavity. At this early stage, the sex of the gonad is indifferent, and the organization of the primitive gonad into a testis is dependent on testis-determining factor (TDF). Differentiation of the primitive gonad into a testis begins at ˜6 weeks of gestation (see Chap. 90 and Chap. 113).

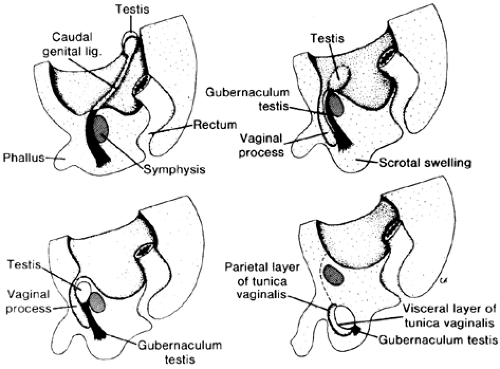

At ˜3 months of gestation, the testis and mesonephros are attached to the posterior abdominal wall by the urogenital mesentery. Shortly thereafter, the mesonephros degenerates, and the mesentery becomes ligamentous and is known as the caudal genital ligament (Fig. 93-5). In the inguinal area, the caudal genital ligament becomes attached to the genital or scrotal swelling and becomes the gubernaculum. With later development, an extension of the peritoneum forms at the medial end of the inguinal ligament, and this traverses the inguinal canal and extends into the scrotum as the processus vaginalis. The distal end of the process normally reaches the scrotum at ˜7 months. Usually, between the sixth and the eighth months of gestation, the testis descends behind the posterior wall of the processus vaginalis, passes through the inguinal canal, and descends into the scrotum; this process is accompanied shortly before birth by a shortening of the gubernaculum. The canal by which the processus vaginalis communicates with the peritoneal cavity usually becomes obliterated shortly after birth. Abdominal pressure is required to push the testis through the inguinal canal. Other essential anatomic factors include absence of any obstruction in the path of descent, an adequately long vas deferens and spermatic vessels, and a normal gubernaculum and epididymis.

FIGURE 93-5. Descent of testis (see text for explanation). (Lig., ligament.) (From Langman J. Medical embryology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1981:263.) |

Present evidence indicates that the process of descent is mediated by the fetal hypothalamic–pituitary–testicular axis.14 Evidence exists that cryptorchidism is often associated with an abnormality of hormonal production. Infants with undescended testes have a deficient plasma LH response to LH-releasing hormone (LHRH, GnRH), and the usual response to the testosterone surge is blunted significantly. Possible causes of cryptorchidism include absence of the gubernaculum or abnormal gubernaculum attachment, abnormal epididymis, lack of abdominal pressure, mechanical obstruction, deficiency of LHRH, pituitary antigonadotropincell autoimmunity (deficient pituitary response to LHRH),15 or failure of the testis to respond to LH. Immunogenetic investigations have demonstrated that the frequency of HLA-A11 and -A23 is significantly higher in cryp-torchid boys than in control subjects.16 The implications of this finding in the etiology of cryptorchidism are not known.

CLASSIFICATION

A useful clinical classification of undescended testes is based on whether the testis is palpable or nonpalpable. Palpable undescended testes are either retractile, ectopic, or undescended within the inguinal canal. Nonpalpable testes may be truly undescended (intraabdominal) or absent (anorchia).

Retractile testes may be anywhere along the normal line of descent, although they are most commonly palpated in the inguinal area. The physician can manipulate the retractile testis into the scrotum with a stroking movement; the testis is retractile because of a very active cremasteric reflex, which causes the gonad to be withdrawn from the scrotum to a higher location. Retractile testes are frequently found in children but are never seen in the neonatal period. Retractile testes usually descend into the scrotum spontaneously when the child sleeps or when he relaxes, as in a warm bath; usually, they are bilateral, in contrast to true undescended testes. This condition does not require any treatment and, by puberty, the testes descend into the scrotum.

The assumption has always been that a descended testis remains descended permanently. However, well-documented instances exist in which previously fully descended testes have been found subsequently to “ascend” permanently out of the scrotum.17 The mechanism of this ascent is unknown. An ascended testis is subject to the same degenerative processes as other cryptorchid testes undergo. The clinician must remember that the finding of a scrotal testes does not rule out the remote possibility of its ascending out of the scrotum.

An ectopic testis is one that has progressed normally through the inguinal canal and emerged from the external ring but has been directed from the scrotum into the suprapubic area, the thigh, or the perineum. In this case, the diagnosis is simple and the therapy is surgical.

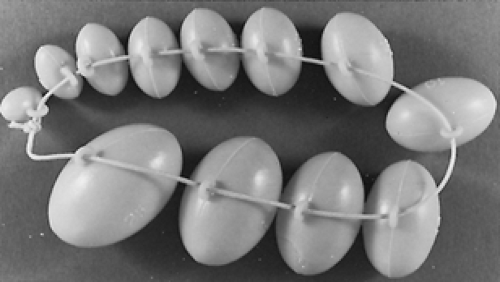

Nonpalpable testes, particularly bilateral ones, present a difficulty in diagnosis. In boys with bilateral nonpalpable testes, various intersex anomalies must be ruled out. In addition to intersex problems, the possibility of anorchia must be considered. Monorchidism occurs more commonly than does bilateral anorchidism. Nonpalpable testes are less likely to descend spontaneously and are usually smaller than normal testes and testes whose descent is arrested closer to the scrotum. Testicular volume (see Table 93-1) may be obtained by comparing the testicular size determined by palpation with an orchidometer, which consists of testicular models of known volumes18 (Fig. 93-6). From ages 7 to 12 years, very little increase in testicular volume occurs. After 12 years of age, size increases markedly until approximately 18 to 19 years of age, when the adult volume is achieved.

INCIDENCE, LOCATION, AND ASSOCIATED ANOMALIES

Two percent to 3% of full-term and 15% to 30% of premature male neonates have a testis that has not completely descended to the scrotum. In ˜25% of patients, the condition is bilateral. Many undescended testes descend by 1 year of age; the incidence of the anomaly is ˜0.7% at 1 year of age. Most of the testes that descend during the first year of life do so within the first 3 months after birth. After 1 year of age, the incidence of cryptorchidism remains between 0.7% and 1.0%,19,20 suggesting that spontaneous descent is unusual after 1 year of age.

In a series of 223 patients, the frequency and position of undescended testes were documented.19 The most common abnormal location was the high scrotal position, which occurred in 44% of patients. In 26% of cases, the testis was in the superficial inguinal pouch; in 20%, it was within the inguinal canal; and in 10%, it was in the abdomen.

Certain well-established syndromes, particularly the more severe chromosomal anomalies, are characterized by cryptorchidism. It is present in half of all male infants with trisomy 13/15 (Patau syndrome, characterized by holoprosencephaly, mental retardation, and cleft lip and palate) and less frequently in those with trisomy 21 (Down syndrome) and trisomy 18 (Edward syndrome, characterized by neonatal hepatitis, mental retardation, skull abnormalities, micrognathia, low-set ears, corneal opacities, deafness, webbed neck, ventricular septal defects, short digits, Meckel diverticulum). Cryptorchidism also occurs in the Prader-Willi syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, Laurence-Moon-Biedl syndrome, and Lowe syndrome (vitamin D–refractory rickets, hydrophthalmia, congenital glaucoma and cataracts, mental retardation, hypophosphatemia, acidosis, and aminoaciduria). Undescended testes may be associated with inguinal hernia, renal anomalies, Wilms tumor, and vasal and epididymal anomalies.21

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree