Controversial and Unproved Methods in Allergy Diagnosis and Treatment

Abba I. Terr MD

Unconventional and unproved theories, procedures, and practices are often referred to as “complementary and alternative medicine” (CAM) (1). Many of these practices are offered to patients with actual or suspected allergy (2), even though there is no evidence that they are either alternative or complementary to rational scientifically-based medical practice.

Accurate diagnosis and effective therapy of allergic disorders can be achieved by relying on sound theory and the results of scientific clinical research. This evidence-based medicine can be accomplished efficiently, safely, and cost effectively. There is little if any justification today for an empirical approach to allergy. However, the clinician who treats allergic patients should be sufficiently knowledgeable about both accepted and unproved theories and techniques in order to counsel their patients.

Definitions

A number of terms have been used to describe different forms of medical practice (Table 44.1).

Table 44.1 Terminology | |

|---|---|

|

Standard practice is generally defined as the methods of diagnosis and treatment used by reputable physicians in a particular subspecialty or primary care practice. Standard practice usually involves a range of options. Procedures should be tailored to the individual patient’s clinical status. In general, physicians who are knowledgeable, trained, and experienced in allergy may prefer certain accepted diagnostic and therapeutic methods while at the same time recognizing that other methods are equally acceptable.

Acceptable methods are based on, or consistent with, currently established mechanisms of allergy. In addition, they have “stood the test of time” through a sufficient period of usage and evaluations by properly conducted scientifically based clinical trials that demonstrate efficacy and safety.

Experimental procedures are potentially new methods of practice arising from the results of scientific studies or from chance empiric observation. Experimental methods of diagnosis and treatment are those undergoing clinical trials on subjects who are informed of the experimental nature of the procedure, their potential risks, and their potential benefits. Subjects must give informed consent to participate in experimental trials.

Controversial methods refer to those procedures that lack scientific credibility and have not been shown to have clinical efficacy, even though they may be used by a few physicians in their practices. They are not used by the majority of allergists. Most of the controversial methods discussed in this chapter have been tested in clinical trials. The published results show either ineffectiveness or insufficient data to establish effectiveness. In some cases only anecdotal testimonies are available. The term unproved is also used for those procedures that are controversial, as defined above.

The terms alternative and complementary are not appropriate, because they tend to obscure the real issue of whether or not a particular procedure has been validated for clinical use by proper scientific scrutiny. Fraud and quackery generally refer to medical practices performed by those individuals who knowingly, deliberately, and deceitfully use unproven and controversial methods for profit. Many physicians who use controversial procedures in allergy practice, however, do so because they sincerely believe that these practices are worthwhile and are unwilling to accept evidence to the contrary.

Standard of care is the terminology usually used in the course of litigation. The definition will vary according to jurisdiction.

Controversial Theories About Allergy

Current allergy practice is based on a foundation of scientifically based immunologic and physiologic principles, thoroughly discussed elsewhere in this book. Some unconventional methods of diagnosis and treatment seemingly derive from these theories, others are based on unsubstantiated theories arising from empirical observations, and still others appear to lack any theoretical foundation. Some of these unconventional theories are discussed in this section.

Allergic Toxemia

Allergic diseases are characterized by focal inflammation in certain target organs. These include the bronchi in asthma; the nasal mucosa and conjunctivae in allergic rhinitis; the gastrointestinal mucosa in allergic gastroenteropathy; the skin in atopic dermatitis, urticaria, and allergic contact dermatitis; and alveolae and lung interstitium in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Multiple target organs are involved in systemic anaphylaxis and in serum sickness. During the course of illness of any of these localized diseases, the allergic patient may experience systemic symptoms such as fatigue or other focal symptoms in parts of the body not directly involved in the allergic inflammation. These collateral symptoms are sometimes explainable pathophysiologically, for example, as secondary effects of hypoxemia and hyperventilation in asthma or from cranial and neck muscle tension from excessive sneezing in rhinitis. Locally released inflammatory mediators and cytokines may produce systemic effects, although direct proof is lacking.

On the other hand, certain practitioners have proposed that a variety of systemic complaints, especially fatigue, drowsiness, weakness, body aching, nervousness, irritability, mental confusion, sluggishness, and poor memory—in the absence of any clinical sign of allergic inflammation–are caused by exposure to environmental allergens. The allergens most often implicated are foods, food additives, environmental chemicals, and drugs. This has been referred to as allergic toxemia, allergic tension fatigue syndrome (3), or cerebral allergy (4). The literature on this subject is largely anecdotal. No definitive controlled studies have yet shown the existence of such a syndrome (5). Patients often claim dramatic improvement from eliminating certain foods or chemicals, but this is not supported by scientific evidence.

The allergic toxemia concept is also used to explain allergy as the cause of certain psychiatric conditions. Attention deficit disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD, ADHD) in children are attributed to food coloring and preservatives (6). Several controlled studies, however, do not support this concept (7). The claim that ingestion of wheat and certain other foods cause or contribute to adult schizophrenia (8,9) has not been confirmed.

Idiopathic Environmental Intolerances (Multiple Chemical Sensitivities)

For years a small group of physicians have accepted a concept that environmental chemicals cause a variety of physical and psychological illnesses. This concept was applied to patients with a host of nonspecific complaints without objective physical signs of disease. These patients also attribute their symptoms to multiple food sensitivities.

This practice is known as clinical ecology (10–12), which postulates disease from failure of the human species to adapt to synthetic chemicals (13). One theory proposes that symptoms represent an exhaustion of normal homeostasis from ingestion of foods and inhalation of chemicals. An alternative theory is that common environmental substances are toxic to the human immune system (14). These and other clinical ecology theories rely on certain unique and unscientific concepts, such as a maximum total body load of antigen, masked food hypersensitivity, and a “spreading phenomenon” whereby the presence of one specific allergy induces others of different specificities.

Clinical ecology practitioners diagnose “environmental illness,” also called multiple chemical sensitivities, ecologic illness, chemical hypersensitivity syndrome, total allergy syndrome, and 20th century disease. The term idiopathic environmental intolerances (IEI) is the most appropriate one, because it avoids unproved mechanisms (15). Patients with this diagnosis generally have a wide range of symptoms that are often compatible with conversion reactions, anxiety and depression, or psychosomatic illness. The diagnosis is subjective with no requirement for any specific physical findings or abnormal laboratory test results.

Lacking a characteristic history or pathognomonic physical signs or laboratory abnormalities (16–18), the diagnosis usually depends on the provocation-neutralization procedure described below. Some clinical

ecologists also measure serum immunoglobulins, complement components, blood level of lymphocyte subsets, and blood or tissue level of environmental chemicals to supplement provocation-neutralization testing. It is not clear, however, how these test results indicate the presence of environmental illness. The few published reports show variable and often conflicting abnormalities of dubious clinical significance, because they lack proper controls or evidence of reproducibility (5).

ecologists also measure serum immunoglobulins, complement components, blood level of lymphocyte subsets, and blood or tissue level of environmental chemicals to supplement provocation-neutralization testing. It is not clear, however, how these test results indicate the presence of environmental illness. The few published reports show variable and often conflicting abnormalities of dubious clinical significance, because they lack proper controls or evidence of reproducibility (5).

The primary treatments advocated by clinical ecologists are avoidance and neutralization therapy. Avoidance of foods believed to cause or aggravate illness is accomplished by a rotary diversified diet, because multiple food “sensitivities” are believed to occur in this illness. Avoidance of all food additives, environmental synthetic chemicals, and even some natural chemicals is recommended, but the extent of avoidance varies with the enthusiasm of the patient and physician and not on scientific evidence of efficacy. Patients often avoid scented household products, synthetic fabrics and plastics, and pesticides. They generally try to limit exposure to air pollutants, gasoline fumes, and vehicle exhaust fumes. Several isolated rural communities have been established for these patients.

Neutralization therapy with food and chemical extracts, megadose vitamin therapy, mineral or amino acid supplements, and antioxidants are commonly recommended. Drug therapy is generally condemned as a form of chemical exposure, although oxygen, mineral salts, and antifungal drugs are frequently prescribed. None of these forms of treatment—either singly or in combination—have been evaluated in properly controlled trials to determine efficacy or potential adverse effects.

Candida Hypersensitivity Syndrome

Environmental illness is also alleged to be caused by Candida albicans normally resident in the microflora of the gastrointestinal and female genitourinary mucous membranes. Many persons with no clinical evidence of Candida infection and no evidence of defective local or systemic immunity, pregnancy, diabetes mellitus, endocrine diseases, or medications known to cause opportunistic candidiasis are said to suffer an illness known as Candida hypersensitivity syndrome (19,20). Clinically, the syndrome is indistinguishable from environmental illness. C. albicans also has been claimed to cause behavioral and emotional diseases and a variety of physical illnesses and symptomatic states. Individuals who have ever received antibiotics, corticosteroids, birth control pills, or have ever been pregnant, even in the remote past, are said to be susceptible to this syndrome. Diagnosis is made by history and not by diagnostic testing. The recommended treatment is avoidance of sugar, yeast, and mold in the diet, and the use of a rotary diversified diet. Nystatin, ketoconazole, caprylic acid, and vitamin–mineral supplements are recommended. This syndrome is reminiscent of the concept of autointoxication that was popular in the early 20th century. In the opinion of some practitioners of that era, the bacterial component of the normal intestinal flora was considered to cause numerous physical and psychologic disabilities (21).

Disease from Indoor Molds

Atmospheric mold sensitivity has recently replaced environmental chemical sensitivity as causing a variety of subjective complaints or illnesses in persons living in homes or working in buildings that have sustained water damage from flooding or excessive humidity, promoting indoor mold growth (22). Fungi are a major component of the environment, and fungal spores are almost always present in the atmosphere. In contrast to well-recognized infectious and allergic diseases caused by molds, a combined toxicity/hypersensitivity theory is often invoked (23) as in the case of environmental illness.

One particular fungus, Stachybotrys atra (chartarum), has created considerable publicity because of the suspicion that Stachybotrys mycotoxin was the causative agent in cases of pulmonary hemorrhage/hemosiderosis in young infants living in water-damaged homes (24). The role of the mycotoxin in these cases has been called into question (25), but there remains unsubstantiated fear of the presence of any indoor mold spores as pathogenic. This unproved theory should not be confused with allergic diseases caused by fungal allergy, especially asthma, some cases of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, and allergic fungal sinusitis. These can be identified by localized symptomatology, objective physical findings, functional and imaging studies that confirm pathology, and the presence of the relevant immune response by the patient.

Other Unconventional Practices

Acupuncture, Chinese herbal therapy, homeopathy, naturopathy, and similar alternative practices have all been used for allergy treatment. None of these are based on accepted scientific principles of physiology, immunology, or pharmacology. Reasonably acceptable clinical trials have failed to show benefit (26–28).

Unconventional Diagnostic Methods

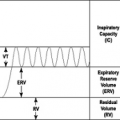

Experienced allergists recognize that a thorough history and physical examination are essential for diagnosis. Laboratory testing is used selectively to supplement the clinical findings, especially when objective measurement

of a functional abnormality such as airway obstruction is desired, or when alternative diagnoses must be considered. In vivo allergy tests such as skin-prick or intradermal tests, patch tests, or in vitro serum antibody tests are procedures that detect the presence of an immune response of a particular type (e.g., immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody or cell-mediated immunity) to a specific allergen. These tests alone do not diagnose or necessarily predict a clinical allergic disease; however, they assist the clinician in diagnosis when the results are correlated with the patient’s history.

of a functional abnormality such as airway obstruction is desired, or when alternative diagnoses must be considered. In vivo allergy tests such as skin-prick or intradermal tests, patch tests, or in vitro serum antibody tests are procedures that detect the presence of an immune response of a particular type (e.g., immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibody or cell-mediated immunity) to a specific allergen. These tests alone do not diagnose or necessarily predict a clinical allergic disease; however, they assist the clinician in diagnosis when the results are correlated with the patient’s history.

Inappropriate diagnostic tests fall into three categories (Table 44.2): (a) procedures of no possible diagnostic value under any circumstances, (b) procedures that are intrinsically capable of a valid measurement but not appropriate for the diagnosis of allergic disorders, and (c) procedures that are intrinsically capable of being used in allergy diagnosis but are not appropriate for general clinical use because of low sensitivity or specificity, lack of general availability, or expense. For example, the in vitro histamine release test has been widely used in allergy research, where it has been invaluable in furthering knowledge of disease, but it cannot be recommended for clinical use at this time. It may eventually be modified to assume a place in allergy practice in the future.

Table 44.2 Categories of Inappropriate Procedures | |

|---|---|

|

“Diagnostic” Procedures of No Value under Any Circumstances

The procedures included in this category are not based on sound scientific principles, and they have not been shown by proper controlled clinical trials to be capable of assisting in the diagnosis of any condition.

The Cytotoxic Test

This is also known as the leukocytotoxic test or Bryan test (29,30). It consists of the microscopic examination of an unstained wet mount of whole blood or buffy coat on a slide that had been previously coated with a food extract. Subjective impressions of leukocyte swelling, vacuolation, crenation, or other changes in morphology are designated as a “positive” test result. This is diagnosed as evidence of allergy to the food. The procedure has not been standardized for time of incubation, pH, osmolarity, temperature, or other conditions that may be responsible for the observed changes (30). Test reproducibility has not been established. The procedure is advertised as a test for allergy to both foods and drugs.

There are currently no allergic diseases known to be caused by leukocyte cytotoxicity from foods, either directly or immunologically. Some drugs do occasionally cause immunologically mediated cytotoxicity (e.g., immune granulocytopenia from cephalothin), but there have been no studies to show that this can be detected in vitro by the Bryan test.

The Antigen Leukocyte Cellular Antibody Test

A modification of the cytotoxic test, the antigen leukocyte cellular antibody test (ALCAT) uses electronic instrumentation and computerized data analysis to examine and monitor changes in cell volumes. Like the cytotoxic test, it also has been promoted as a screening procedure for diagnosing food allergy or intolerance in a host of conditions, including arthritis, urticaria, bronchitis, gastroenteritis, childhood hype-reactivity, rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis. Results are used to recommend elimination diets for these diseases. There are no proper controlled trials to establish diagnostic efficacy (33).

Provocation–Neutralization

This is a procedure that is claimed by its proponents to diagnose “allergy” to foods, inhalant allergens, environmental chemicals, hormones, and microorganisms, such as Candida albicans. The patient is given a small dose of an extract of one of these substances by either intracutaneous injection, subcutaneous injection, or by sublingual drop. Any subjective “sensations” (i.e., symptoms) during the next 10 minutes are recorded as a positive test result, diagnosed as allergy to that substance. If the test is negative (i.e., no recorded sensations), it is repeated at higher concentrations until the patient reports a sensation. Progressively lower concentrations are then administered, and if fewer or no symptoms are reported, the reaction is said to be “neutralized” (34–41). The neutralizing dose is then used as ongoing therapy. The test result is graded as positive regardless of whether or not the reported sensations are the same as those in the patient’s initial history. When the test is performed by intradermal injection, increasing wheal diameter with increasing dose is considered corroborative evidence of a positive test result. Some proponents measure change in pulse rate during the test, but there is disagreement about its significance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree