Roberta L. DeBiasi, Kenneth L. Tyler

Coltiviruses and Seadornaviruses

Coltivirus and Seadornavirus are two of five genera of the Reoviridae virus family that have been documented to cause human disease; Orthoreovirus, Orbivirus, and Rotavirus are discussed in Chapters 150 and 152. Like all Reoviridae, coltiviruses and seadornaviruses are nonenveloped double-stranded RNA viruses with a segmented genome. Coltiviruses have 12 gene segments enclosed within two capsids. Coltiviruses were classified within the Orbivirus genus until 1991, at which time their distinct molecular identity was established, and a unique genus was proposed.1–4 Coltiviruses were initially subclassified into the tick-borne subgroup A (North American and European distribution) and mosquito-borne subgroup B (Asian distribution) viruses. In the year 2000, subgroup B coltiviruses were reclassified into the newly designated genus Seadornavirus (an acronym for Southeast Asian dodeca RNA virus) based on sequence data and antigenic properties. Coltiviruses associated with human disease include the type-specific Colorado tick fever virus (CTFV; North America), Eyach virus (EYAV; France, Germany, Czech Republic), and Salmon River virus (SRV; North America). The only Seadornavirus implicated in human disease to date is Banna virus (BAV; Indonesia and China). However, Seadornavirus infection is considered an emerging infectious disease, and the full spectrum of human disease is likely underrecognized.3,5–7 Although not yet isolated from humans, the seadornaviruses Liao ning and Kadipiro have been isolated from mosquitoes and replicate well in mice,3,8 suggesting the potential for human infection.

Coltiviruses

Colorado Tick Fever Virus

Epidemiology

A recent comprehensive review of CTFV indicated that up to 400 cases are reported in the United States each year, making it the second most commonly identified arboviral infection in the United States, after West Nile virus.9 A more recent study through 2003 indicated the incidence may be declining, for unknown reasons.10 Cases were 2.5 times more frequent in males than females. The highest incidence of cases occurred in persons aged 51 to 70. Tick exposure prior to illness onset was reported in 90% of the cases.10 Ticks are the principal vectors of coltiviruses, but viruses have also been isolated from mosquitoes, rodents, and humans.6,11 Coltiviruses exhibit a high frequency of RNA segment reassortment in tick vectors.12 CTFV is maintained in an epizootic cycle between the principal vector, Dermacentor andersoni, and small mammals such as porcupines, ground squirrels, and chipmunks. Humans are infected by the bite of adult ticks.9,13 The geographic distribution of the type-specific CTFV includes China, Europe, and North America. In the United States, the distribution of CTFV coincides with the range of the principal vector, D. andersoni. The virus has been isolated in 11 states, primarily within the Rocky Mountain region (California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming) as well as southwestern Canada.9 Most cases occur in Colorado, Montana, Utah, and Wyoming.9 Elevations of 4000 to 10,000 feet and rocky outcroppings are especially suited to CTFV.9,13,14 Transmission coincides with the seasonal activity of D. andersoni ticks, with most cases occurring between April and July.9 Disease transmission can occur even as a consequence of brief tick attachment, in contrast with the requirement for prolonged tick attachment for transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi or Rickettsia ricketsii.9 Ninety percent of patients report tick exposure, but only 48% recall tick attachment.15 Half of reported cases occur in patients between 20 and 49 years of age, with an additional 25% occurring in patients younger than 20 years.9,15 Transfusion-related symptomatic infection has been reported.16 CTFV patients should not be allowed to serve as blood product or hematopoietic stem cell donors until infection has fully resolved, and reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assays on blood are negative, a process that may take 4 months or longer (see later). Intrauterine transmission during human pregnancy has resulted in the birth of healthy infants but also has been potentially associated with spontaneous abortion and other congenital anomalies.17 Laboratory transmission cases have also been reported.

Clinical Features

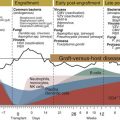

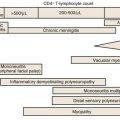

CTFV has been isolated from patients with acute febrile syndromes, meningitis, and encephalitis in North America. The first published clinical descriptions of CTFV appeared as early as 1855 with identification of the virus in 1946 after isolation from human serum.9,18 At least 22 strains of CTFV have been described,19 many of which cause disease in humans. Onset of symptoms usually occurs after an incubation of 3 to 5 days (range, 0 to 14 days).9,15,20 Symptoms classically include abrupt onset of fever, chills, and headache, which may be accompanied by retro-orbital pain, photophobia, conjunctivitis, myalgia, generalized weakness, or lethargy.9,15,20 Other reported clinical findings include pharyngitis (20% of patients), palatal enanthem, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and splenomegaly.9,15,20 Rash occurs in a minority (5% to 12%) of patients and has been described as macular, maculopapular, or petechial.9 Fever typically lasts 2 to 3 days and either resolves completely or, in 50% of cases, recurs after a period of 1 to 3 days of fever remittance (although malaise may continue), described as the saddleback fever pattern. This second phase of febrile illness lasts about 2 days.15,20 Full resolution of symptoms typically occurs within 1 week. Older patients (>30 years or age) may have fatigue, persisting for weeks to months.9 Neurologic complications (aseptic meningitis, meningoencephalitis, or encephalitis) are more common in the pediatric population, occurring in up to 10% of symptomatic children.9 Other rarely reported complications include myocarditis, pericarditis, pneumonitis, hepatitis, and epididymo-orchitis.6,9,19 Severity of illness is sufficient to necessitate hospitalization in up to 20% of CTFV patients.6 Mortality has not been reported in adults and is rare in children, with deaths reported in the pediatric population secondary to hemorrhagic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, or meningoencephalitis.9,15,20

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree