Colon Resection

CRITICAL ELEMENTS

Abdominal Exploration

Extent of Bowel Mobilization and Resection

Proximal Vascular Ligation and Regional Lymphadenectomy

Multivisceral Resection

Removal of Lymphadenopathy Beyond the Primary Distribution

1. ABDOMINAL EXPLORATION

Recommendation: A thorough exploration of the peritoneal cavity should be performed at the time of surgery, and the findings of this exploration should be recorded in the operative report.

Type of Data: Retrospective observational studies and expert consensus.

Strength of Recommendation: Strong.

Rationale

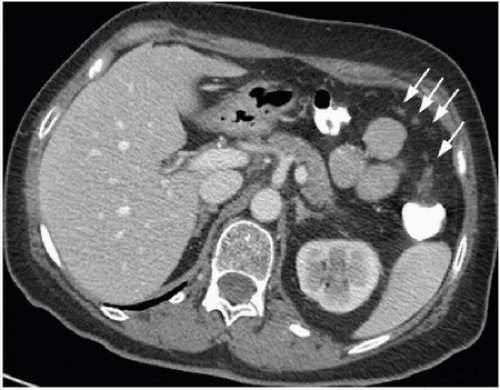

The operative management of colon cancer should begin with a thorough exploration of the abdominal cavity.1,2 The rationale for this exploration is unassailable; appropriate treatment requires accurate staging, and unexpected findings may warrant a change in the surgical approach. Some patients’ surgeries will yield unanticipated findings regardless of the type and quality of preoperative imaging performed, an eventuality supported by previous studies. For example, one study reported that the sensitivity of preoperative computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging,3 and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for the detection of liver metastases ranges from 74% to 81% on a per lesion basis, suggesting that a significant number of metastatic lesions may be below the limit of identification and go undetected prior to surgery.4 Another study found that although preoperative CT could detect liver metastases in 99% of patients,

it could detect locally advanced lesions in 86% of patients and peritoneal carcinomatosis in only 33% of patients5 (Fig. 16-1). Few studies have specifically investigated the potential impact of abdominal exploration on survival or the frequency with which findings from such an exploration alter planned treatment in the era of modern preoperative staging. Given the importance that a complete evaluation has for both treatment and prognosis, however, we support existing guidelines advocating this approach.

it could detect locally advanced lesions in 86% of patients and peritoneal carcinomatosis in only 33% of patients5 (Fig. 16-1). Few studies have specifically investigated the potential impact of abdominal exploration on survival or the frequency with which findings from such an exploration alter planned treatment in the era of modern preoperative staging. Given the importance that a complete evaluation has for both treatment and prognosis, however, we support existing guidelines advocating this approach.

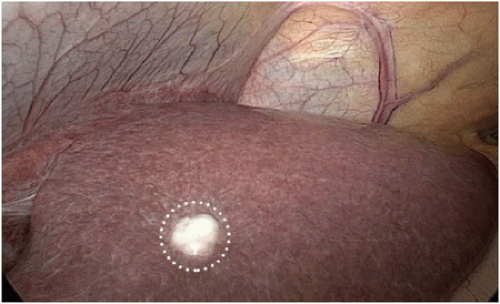

A thorough abdominal exploration should be performed regardless of whether a minimally invasive or open operative approach is used. To the extent possible without subjecting the patient to additional risk, the surgeon should examine the liver, peritoneal surfaces, omentum, mesentery, regional and extraregional (e.g., periaortic or periportal) lymph nodes, retroperitoneum, and adnexa (if present) and document the findings of this examination (Figs. 16-2, 16-3 and 16-4). The surgeon should also evaluate

primary tumor site for the presence or absence of full-thickness extension through the bowel wall and the presence of a confirmatory tattoo, if applicable (Fig. 16-5). The surgeon should also note the presence of ascites or other coexisting pathology. If it has not been completely evaluated preoperatively, the proximal colon should be examined for the presence of a synchronous cancer. The identification of unsuspected carcinomatosis during initial exploration indicates the presence of systemic disease. In an otherwise asymptomatic patient, primary tumor resection in this setting is contraindicated and the early initiation of systemic therapy should be considered. If the peritoneal disease is limited and favorable tumor biology has been demonstrated by the tumor’s response to systemic therapy, subsequent resection with cytoreduction may be considered in the context of multidisciplinary treatment.

primary tumor site for the presence or absence of full-thickness extension through the bowel wall and the presence of a confirmatory tattoo, if applicable (Fig. 16-5). The surgeon should also note the presence of ascites or other coexisting pathology. If it has not been completely evaluated preoperatively, the proximal colon should be examined for the presence of a synchronous cancer. The identification of unsuspected carcinomatosis during initial exploration indicates the presence of systemic disease. In an otherwise asymptomatic patient, primary tumor resection in this setting is contraindicated and the early initiation of systemic therapy should be considered. If the peritoneal disease is limited and favorable tumor biology has been demonstrated by the tumor’s response to systemic therapy, subsequent resection with cytoreduction may be considered in the context of multidisciplinary treatment.

2. EXTENT OF BOWEL MOBILIZATION AND RESECTION

Recommendation: The length of colon to be resected is determined by the primary tumor’s location with respect to the colon’s associated arterial supply.

Type of Data: Retrospective observational studies and expert consensus.

Strength of Recommendation: Moderate.

Rationale

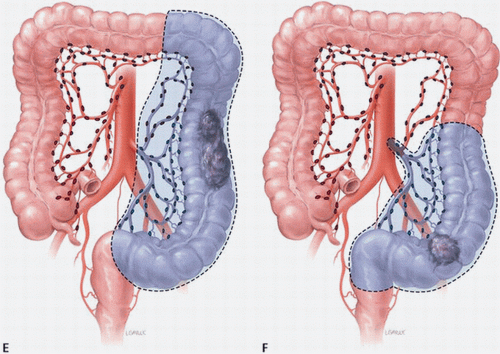

The lymphatics parallel the arterial supply (Fig. 16-6). The lymphatic drainage of the right colon and proximal transverse colon courses along the branches of the superior mesenteric artery. The lymphatics of the distal transverse colon, descending colon, and sigmoid colon segments drain along the course of the inferior mesenteric artery. Lymphatic drainage is often continuous, first from the pericolonic lymph nodes, then to the intermediate lymph nodes along the right colic artery, middle colic artery, left colic artery, and sigmoid arteries and then to the central nodes at the origin of the superior or inferior mesenteric artery. In general, the extent of bowel mobilization is dictated by the colonic blood supply and whether mesenteric resection will be adequate to provide an appropriate assessment of the associated lymph nodes. The resection of carcinoma located between two drainage areas should include both lymphatic drainage pathways, which may require that a longer segment of colon be removed (Fig. 16-7A-F).

The surgical margin generally accepted to result in an R0 resection for colon cancer is 5 cm. In most circumstances, however, the margin will be greater depending on the arterial supply to the involved colon segment, emphasizing the importance of the blood supply and its impact on the lymphatic drainage rather than simple length of the colon. The surgical margin is particularly important in patients with locally advanced

lesions (T3 or T4 disease). Whereas stage I and II cancers have low recurrence rates, stage III cancers have a high risk of recurrence even if the resection margins are at least 5 cm.6 An oncologic advantage of extended resection (e.g., resection of the terminal ileum during right colectomy or subtotal colectomy for a single tumor in the absence of underlying risk) has not been shown.

lesions (T3 or T4 disease). Whereas stage I and II cancers have low recurrence rates, stage III cancers have a high risk of recurrence even if the resection margins are at least 5 cm.6 An oncologic advantage of extended resection (e.g., resection of the terminal ileum during right colectomy or subtotal colectomy for a single tumor in the absence of underlying risk) has not been shown.

Extended resection may be indicated in certain clinical situations. For example, patients who present with synchronous cancers may be treated with two separate resections based on arterial supply (e.g., right colectomy and anterior resection for synchronous tumors of the cecum and sigmoid colon) or with a single resection that incorporates both tumors (e.g., subtotal colectomy for synchronous tumors of the hepatic flexure and descending colon).2 A subtotal colectomy may be indicated in

patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, as they have a higher incidence of synchronous and metachronous colonic tumors than do patients with sporadic colorectal cancer. As calculated by life table analysis, the risk for metachronous cancer among patients with hereditary nonpolyposis is as high as 40% at 10 years. Similarly, for colon cancer patients with familial adenomatous polyposis, surgical resection should consist of either total abdominal colectomy or total proctocolectomy. The choice between these two operations depends on the burden of polypoid disease in the rectum and the patient’s preference for close surveillance.7,8,9 Finally, individuals who develop colon cancer in the setting of long-standing ulcerative colitis require a total proctocolectomy. The oncologic principles of colon cancer surgery as outlined in this chapter, including the attention to surgical margins and the need for proximal vascular ligation, should be adhered to bilaterally, not just for the portion of colon in which the tumor has been identified.10,11

patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, as they have a higher incidence of synchronous and metachronous colonic tumors than do patients with sporadic colorectal cancer. As calculated by life table analysis, the risk for metachronous cancer among patients with hereditary nonpolyposis is as high as 40% at 10 years. Similarly, for colon cancer patients with familial adenomatous polyposis, surgical resection should consist of either total abdominal colectomy or total proctocolectomy. The choice between these two operations depends on the burden of polypoid disease in the rectum and the patient’s preference for close surveillance.7,8,9 Finally, individuals who develop colon cancer in the setting of long-standing ulcerative colitis require a total proctocolectomy. The oncologic principles of colon cancer surgery as outlined in this chapter, including the attention to surgical margins and the need for proximal vascular ligation, should be adhered to bilaterally, not just for the portion of colon in which the tumor has been identified.10,11

3. PROXIMAL VASCULAR LIGATION AND REGIONAL LYMPHADENECTOMY

Recommendation: Resection of the tumor-bearing bowel segment and radical lymphadenectomy should be performed en bloc with proximal vascular ligation at the origin of the primary feeding vessel(s).

Type of Data: Prospective and retrospective observational studies.

Strength of Recommendation: Moderate.

Rationale

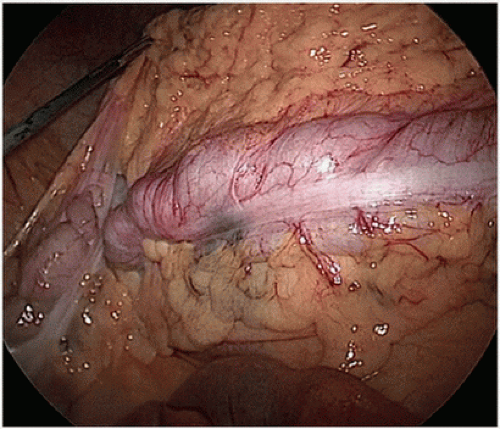

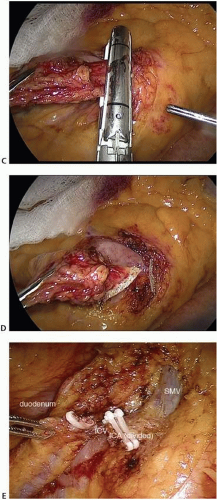

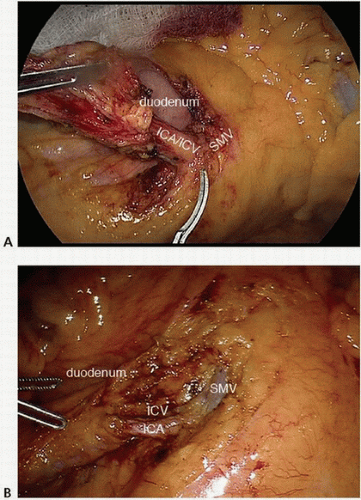

The standard of practice for the treatment of stage I to III (nonmetastatic) colon cancer is complete margin-negative resection (R0 resection) of the tumor-bearing bowel combined with en bloc resection of the intact node-bearing mesentery (i.e., regional lymphadenectomy). Regional lymphadenectomy is guided by the anatomy of the regional blood supply to the tumor-bearing bowel segment. Complete standard lymphadenectomy is facilitated by the proximal ligation of the relevant vascular pedicle of the tumor-bearing bowel segment. The pedicles that may be ligated on the basis of tumor location include the ileocolic (Fig. 16-8A-E), right colic (Fig. 16-9A,B), middle colic

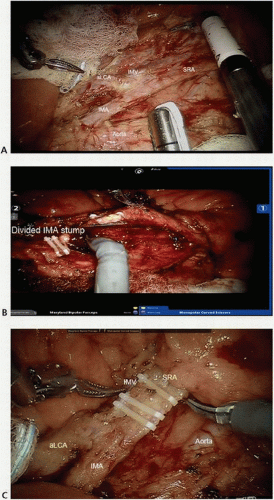

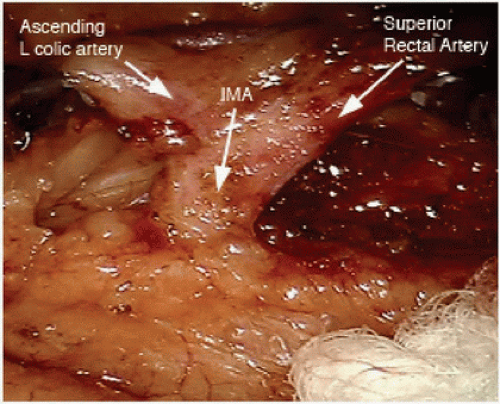

(Fig. 16-10A,B), left colic (Fig. 16-11), inferior mesenteric (Fig. 16-12A,B), and superior hemorrhoidal arteries and associated veins (Fig. 16-12C), which are identified centrally at the root of the colonic mesentery. Thus, the vascular anatomy of the tumor-bearing colon segment should be clearly identified, with attention to the potential anatomic variations that are commonly encountered. After the vascular ligation has been completed, the integrity of the blood supply to the remaining bowel should be carefully assessed by direct inspection of the bowel wall for adequate perfusion, visualization of pulsatile blood flow within the terminal vessels, or Doppler interrogation of the arterial supply. Although the marginal artery provides a collateral network between the primary vascular supplies, the artery may have congenital and/or acquired variations in its integrity and is subject to injury during colon mobilization.

(Fig. 16-10A,B), left colic (Fig. 16-11), inferior mesenteric (Fig. 16-12A,B), and superior hemorrhoidal arteries and associated veins (Fig. 16-12C), which are identified centrally at the root of the colonic mesentery. Thus, the vascular anatomy of the tumor-bearing colon segment should be clearly identified, with attention to the potential anatomic variations that are commonly encountered. After the vascular ligation has been completed, the integrity of the blood supply to the remaining bowel should be carefully assessed by direct inspection of the bowel wall for adequate perfusion, visualization of pulsatile blood flow within the terminal vessels, or Doppler interrogation of the arterial supply. Although the marginal artery provides a collateral network between the primary vascular supplies, the artery may have congenital and/or acquired variations in its integrity and is subject to injury during colon mobilization.

FIGURE 16-8 A-E: Intraoperative images of ileocolic vessel dissection and ligation. ICA, ileocolic artery; ICV, ileocolic vein; SMV, superior mesenteric vein. |

FIGURE 16-9 A,B: Intraoperative images of right colic artery dissection. ICA, ileocolic artery; RCA, right colic artery; SMA, superior mesenteric artery; SMV, superior mesenteric vein. |

FIGURE 16-11 Intraoperative image showing the IMA giving rise to the left colic and superior rectal arteries. IMA, inferior mesenteric artery. |

Proximal vascular ligation with en bloc lymphadenectomy ensures complete resection of the associated lymph nodes for pathologic evaluation. The number of lymph nodes resected surgically and evaluated pathologically reflects the completeness of lymphadenectomy and is an indicator of surgical quality and oncologic outcome.

The term “complete mesocolic excision” (CME) has been used to describe en bloc complete resection along embryologic planes of the tumor-bearing colon and associated mesentery with its investing envelope intact and without defects. To ensure the integrity and completeness of the bowel and lymphatic excision at the time of colon cancer surgery, some groups have emphasized the practice of complete mesocolic excision (CME) and central ligation of the arteries and draining veins.12 Observing the CME principles during resection has been associated with lower risks of margin positivity and iatrogenic tumor perforation. One retrospective review of a large, single-institution database demonstrated that the adoption of CME in colon cancer surgery decreased the 5-year local recurrence rate from 6.5% to 3.6% and improved the 5-year overall survival rate from 82.1% to 89.1%.13 The new terminology that accompanies the adoption of CME highlights the principles of standard oncologic resection (en bloc complete resection of the associated lymph nodes) and provides a standardized method for operative technique and pathologic evaluation.

4. MULTIVISCERAL RESECTION

Recommendation: Involved adjacent organs and structures should be removed en bloc with the primary tumor.

Type of Data: Retrospective observational studies.

Strength of Recommendation: Strong.

Rationale

Colorectal cancer involving adjacent structures (T4b disease) is reported to occur in 5% to 15% of patients3,14 and is often appreciated by history, examination, and/or staging studies (Fig. 16-13). En bloc resection of the primary tumor, associated lymph node basin, and involved adjacent structures is a key oncologic principle for colon cancer surgery and a key factor in maintaining local disease control. Consensus guidelines, National Cancer Institute (NCI), American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN Guidelines 2014) recommend en bloc multivisceral resection of locally advanced disease when there is acceptable morbidity and curative potential.3,15

En bloc resection requires removal of the tumor-bearing segment of bowel and attached structures as a single unit. The dissection of a tumor off the bladder followed later by the removal of the portion of bladder to which the tumor was attached is not an en bloc resection. Similarly, the removal of the surgical specimen and subsequent, separate removal of the lymph node-bearing mesentery associated with the tumorbearing segment is not an en bloc resection.

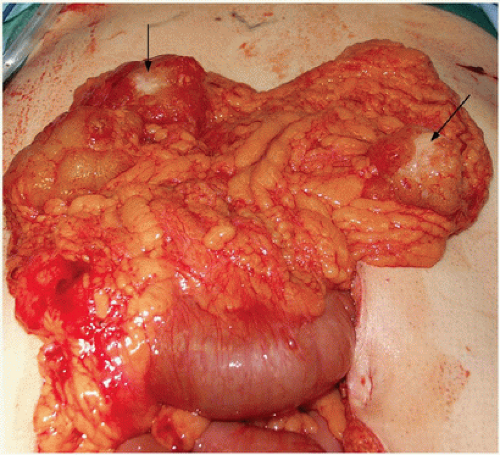

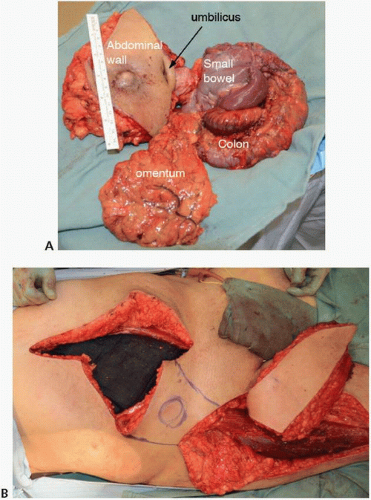

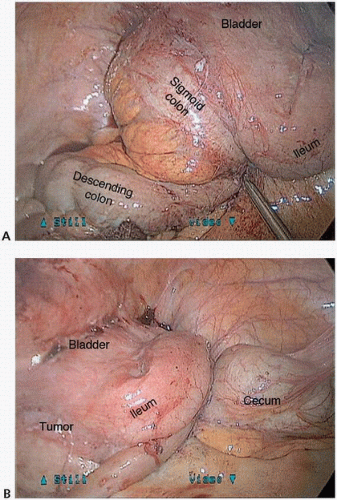

At the time of surgical exploration, adherence of the tumor-bearing colon segment to adjacent structures may be due to inflammatory adhesions or to malignant invasion (Fig. 16-14A,B). Intraoperative assessment can be unreliable for distinguishing between an inflammatory or malignant adhesion; false positive rates range from 30% to 50%.16,17 Attempting to separate planes risks incomplete oncologic resection. Therefore, gross adherence of tumor requires en bloc resection (Fig. 16-15). Determining whether a colon cancer involving adjacent organs is resectable requires a clear understanding of the anatomic boundaries required to attain negative margins, the potential for injury to adjacent structures, and the overall morbidity of the required procedure. Omitting any one of these in considering whether complete resection is a prudent

option may result in unacceptably high morbidity. If the extent of resectability cannot be fully assessed, or if the patient and/or operative team are not adequately prepared for the extent of resection (e.g., if there is a need for multidisciplinary surgical support), the surgeon should consider performing a temporizing diversion or bypass. This should be followed by careful radiographic staging and operative planning for later definitive resection.

option may result in unacceptably high morbidity. If the extent of resectability cannot be fully assessed, or if the patient and/or operative team are not adequately prepared for the extent of resection (e.g., if there is a need for multidisciplinary surgical support), the surgeon should consider performing a temporizing diversion or bypass. This should be followed by careful radiographic staging and operative planning for later definitive resection.

FIGURE 16-14 A,B: Intraoperative photograph of a locally advanced sigmoid colon cancer with bladder, ileum, and descending colon involvement. |

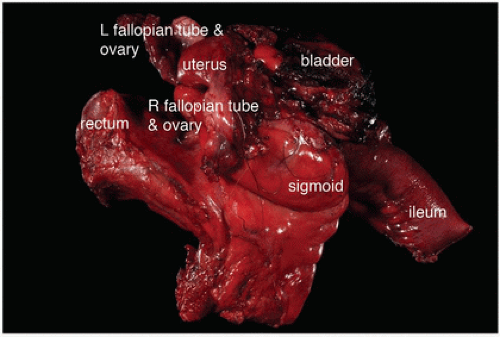

FIGURE 16-15 En bloc multivisceral resection specimen including the sigmoid colon, rectum, terminal ileum, uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries, and bladder. |

En bloc resection that includes structures in which removal would result in low morbidity—the small bowel, ovary, or abdominal wall, for example—should be performed in almost all situations. Major resections likely to result in high morbidity, such as pelvic exenteration, nephrectomy, pancreaticoduodenectomy, or major nerve or vascular resection, should be preceded by careful surgical preparation and preoperative patient counseling. Multivisceral resection of advanced-stage colon cancer poses many challenges to the operating surgeon and may be associated with significant morbidity. There are situations in which aggressive multivisceral en bloc resection provides the only chance for cure. Unfortunately, there are situations in which the surgery would be futile or result in unacceptably high morbidity; thus, the decision to proceed with resection should be based on a thorough preoperative evaluation and a discussion with the patient and the patient’s multidisciplinary care team. Proper planning includes review of imaging to determine the plan for both resection and reconstruction and assessment of patient’s functional status.

Morbidity rates following multivisceral resection range from 25% to 40% with 30-day mortality rates ranging from 4% to 9%.3,14,18 However, these data from singleinstitution reports reflect careful patient selection and treatment by experienced surgeons with coordinated multidisciplinary teams and recovery units. Thus, the patient’s comorbid factors and the surgeon’s experience should be considered in the management of these complex tumors. The need for thorough preoperative planning to reduce morbidity, including contingency plans, cannot be overemphasized.19 A more detailed description of some specific situations of adjacent organ involvement is outlined in the sections below.

Duodenum and pancreas. Locally advanced cancer in the right colon may extend directly into the duodenum or pancreatic head or neck. The resection of such cancer may entail en bloc pancreaticoduodenectomy or partial duodenectomy. Fortunately, only a very small proportion of locally advanced T4 colon cancers involve the pancreas (1.7% to 8%) or duodenum (0.8% to 4%). Direct tumor infiltration (pT4b disease) of the duodenum or pancreatic head suspected on the basis of tumor adhesion is pathologically confirmed in 20% to 78% of patients, which demonstrates the variability in the presentation of such tumors and the difficulty in clinically assessing whether pathologic invasion is present.3 Depending on the series, the risk for surgical morbidity is approximately 25% and that for surgical mortality is as high as 20%. In the setting of perforation or abscess, the surgical mortality rate is particularly high. Other adverse prognostic factors include nodal and distant metastasis; in the presence of such metastasis, the rate of early recurrence approaches 50% at a median time of 15 months. Regardless of the limited published evidence guiding surgery for colon cancer invading the duodenum and/or pancreas, the fundamental principles of

oncologic resection should be maintained. The tumor should never be dissected off the duodenal wall or pancreas. In healthy, well-selected patients, partial duodenal wall resection can be performed by a surgeon who has the necessary skills and experience. Pancreaticoduodenectomy can be offered only if the need for it is recognized preoperatively, but the surgery should be preceded by proper counseling and multidisciplinary discussion that includes the consideration of neoadjuvant therapy. For symptomatic high-risk scenarios, temporizing adjuncts include gastrostomy, feeding jejunostomy, and ileostomy or gastrojejunostomy bypass.

oncologic resection should be maintained. The tumor should never be dissected off the duodenal wall or pancreas. In healthy, well-selected patients, partial duodenal wall resection can be performed by a surgeon who has the necessary skills and experience. Pancreaticoduodenectomy can be offered only if the need for it is recognized preoperatively, but the surgery should be preceded by proper counseling and multidisciplinary discussion that includes the consideration of neoadjuvant therapy. For symptomatic high-risk scenarios, temporizing adjuncts include gastrostomy, feeding jejunostomy, and ileostomy or gastrojejunostomy bypass.

Ureters and bladder. En bloc R0 resection is often appropriate for tumors invading urologic structures in the pelvis. The bladder is the most commonly involved organ among patients with colorectal cancer, resected in 53% of cases in a large systematic literature review.18 In a recent series in which only bladder involvement was treated with limited bladder wall resection, malignant adhesions increased the risk of local recurrence at the bladder tenfold.20 Thus, the importance of wide, complete, and en bloc resection should be emphasized. However, following composite resection of the urinary tract for colon cancer, up to one in four patients will have urologic complications and that many of these patients (27%) will ultimately require surgical correction.21 Thus, a multidisciplinary approach to management of patients with colon cancer involving the urologic tract should be considered.

Uterus and ovaries. Female pelvic organs may be involved in both right- and leftsided colonic malignancies. Colon cancer involvement of the ovaries can occur via direct extension, peritoneal dissemination, or hematogenous spread. Approximately 20% of multivisceral resections for colon cancer are associated with ovarian involvement.18 The uterus and vagina may also become involved, although this is more commonly an issue in the setting of rectal cancer rather than colon cancer. Oophorectomy is advocated if there is clinical suspicion of ovarian involvement in the absence of disseminated peritoneal metastasis. Direct extension of the tumor into any female pelvic organs can be resected en bloc with curative intent and minimal morbidity.

The role of prophylactic oophorectomy in patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer has been a subject of some interest. The surgery can be performed with minimal morbidity, particularly among postmenopausal women. A survival benefit with prophylactic oophorectomy in patients with sporadic colorectal cancer has not been demonstrated.22,23,24,25 Prophylactic oophorectomy should be considered and the indications preoperatively discussed for colon cancer patients who have hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome, as these patients are at risk for both occult synchronous and subsequent metachronous ovarian malignancy.26,27 Prophylactic oophorectomy not only reduces the risk for ovarian cancer but has also been shown to be cost-effective.28

Abdominal wall and diaphragm. Abdominal wall invasion should be resected en bloc with negative margins. Preoperative planning for colorectal cancers invading the abdominal wall and/or diaphragm should include consultation with a reconstructive surgery team. Partial-thickness abdominal wall defects resulting from such resection may not require vascularized flap-based reconstruction but may be repaired primarily or

with bioprosthetic or synthetic mesh replacement of the fascia. Full-thickness abdominal wall defects and/or those with skin involvement likely require reconstruction with a vascularized flap (Fig. 16-16). There are various options for temporary and definitive abdominal wall reconstruction. Concerns about the risk for subsequent hernia should not preclude aggressive resection. However, if the need for abdominal wall resection has not been preoperatively anticipated and immediate reconstructive options are unavailable, aborting the resection with planned subsequent return to surgery with a multidisciplinary surgical team should be considered. Diaphragm involvement is not a contraindication to en bloc resection, and primary or mesh (e.g., bioprosthetic) closure in patients with diaphragm involvement may be performed. Such an approach has been performed among patients undergoing liver resection, and although associated with potentially increased morbidity, it does not increase operative mortality.29 However, the dissemination of cancer cells into the thoracic cavity either prior to exploration or

due to iatrogenic tumor seeding will limit the utility of this effort. Avoiding injury to the phrenic nerve improves postoperative respiratory recovery.

with bioprosthetic or synthetic mesh replacement of the fascia. Full-thickness abdominal wall defects and/or those with skin involvement likely require reconstruction with a vascularized flap (Fig. 16-16). There are various options for temporary and definitive abdominal wall reconstruction. Concerns about the risk for subsequent hernia should not preclude aggressive resection. However, if the need for abdominal wall resection has not been preoperatively anticipated and immediate reconstructive options are unavailable, aborting the resection with planned subsequent return to surgery with a multidisciplinary surgical team should be considered. Diaphragm involvement is not a contraindication to en bloc resection, and primary or mesh (e.g., bioprosthetic) closure in patients with diaphragm involvement may be performed. Such an approach has been performed among patients undergoing liver resection, and although associated with potentially increased morbidity, it does not increase operative mortality.29 However, the dissemination of cancer cells into the thoracic cavity either prior to exploration or

due to iatrogenic tumor seeding will limit the utility of this effort. Avoiding injury to the phrenic nerve improves postoperative respiratory recovery.

5. REMOVAL OF LYMPHADENOPATHY BEYOND THE PRIMARY DISTRIBUTION

Recommendation: Clinically positive lymph nodes outside the primary field of resection that are identified at the time of resection should be biopsied or removed.

Type of Data: Retrospective observational studies.

Strength of Recommendation: Moderate.

Rationale

Lymphatic vessels course along the distribution of the mesenteric vessels. Drainage from the intestine courses toward the root of the mesentery, along the para-aortic nodes, and ultimately into the thoracic duct. Lymphatics in the cecum and proximal ascending colon most commonly drain along the ileocolic lymph nodes, which encircle the ileocolic vascular pedicle. Metastases from tumors of the ascending colon may be present in lymph nodes along the ileocolic, right, and middle colic arteries. Lymph drainage from the transverse colon is primarily along the middle colic artery and then into the superior mesenteric lymph group.30

The inferior mesenteric lymph nodes, which are situated about the root of the inferior mesenteric artery, are afferent from peripheral nodes located along the marginal artery of Drummond and efferent to the lumbar nodal chain and superior mesenteric nodes.

Clinical Implications

In addition to the aforementioned primary routes of its lymphatic spread, colorectal cancer metastasis can also occur beyond the primary distribution and outside of the distribution of the primary resection along the following routes:

Para-aortic nodes. The para-aortic nodes are situated anterior to the lumbar vertebral bodies in proximity to the abdominal aorta. The para-aortic node group can be divided into three subgroups:

Preaortic group: These nodes drain the abdominal part of the gastrointestinal tract superior to the mid-rectum.

Retroaortic group: These nodes drain the lateral and preaortic regions.

Lateral group: These nodes, which drain the iliac regions, ovaries, and other pelvic organs, are located adjacent to the aorta and anterior to the spine. They extend laterally to the edge of the psoas major muscles and superiorly to the diaphragm.

Colorectal metastasis to the para-aortic nodes are uncommon but associated with poor prognosis. Metastases to the para-aortic lymph nodes most commonly occur in the preaortic or lateral groups, although multiple lymph nodes may be involved. The presence of para-aortic lymph node involvement signals the need for systemic chemotherapy and, when identified at surgery, should be removed for pathologic evaluation.

Nodes within the small bowel mesentery (SBM). The root of the SBM is contiguous with the hepatoduodenal ligament around the superior mesenteric vein and the right side of the transverse mesocolon about the gastrocolic trunk. The inferior mesenteric vein runs along the left side of the root of the SBM. Colon cancer cells can spread to the SBM by direct extension, by extension along the neural plexus or neighboring ligaments, or by way of lymphatic channels. Much like that of para-aortic nodes, colorectal cancer involvement in this node group is associated with poorer prognosis, and the clinical significance of extended dissection into this distribution remains incompletely understood.

The lymphatic spread of colon cancer from the submucosal lymphatic channels through the epi- and paracolic nodes to the intermediate nodes and then to nodes surrounding the superior mesenteric artery and/or para-aortic nodes was once considered to be an orderly and predictable process of tumor cell dissemination. Sentinel lymphatic mapping studies have shown aberrant lymphatic drainage in approximately 4% of cases (range, 0% to 10%).31 However, these studies often do not specify the precise anatomical location(s) of the aberrant node(s). Aberrant lymphatic drainage beyond the relevant nodes in the central vascular pedicle may be identified as clinically abnormal lymph nodes by their size or other characteristics and should be resected for pathologic evaluation if it is safe to do so.

Intraoperative Assessment

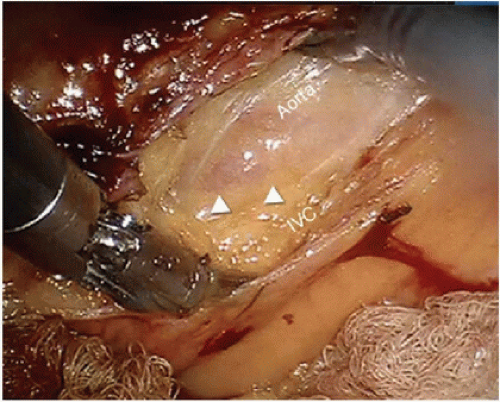

The standard preoperative clinical evaluation of patients with nonmetastatic colon cancer includes CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. During this evaluation, the patient should be carefully evaluated for enlarged lymph nodes along the superior mesenteric artery, superior mesenteric vein, and iliac vessels and about the abdominal aorta. Clinically suspicious lymph nodes (i.e., >1 cm) should be thoroughly evaluated and potentially resected at the time of operation (Fig. 16-17A,B). During the operation, the retroperitoneum and root of the mesentery should be carefully evaluated as part of routine exploration, and abnormal-appearing lymph nodes should be identified and resected for histologic evaluation.

FIGURE 16-17 Intraoperative photograph showing aortocaval adenopathy. Triangles point to lymph node. IVC, inferior vena cava. |

The vast majority of lymph nodes in colon cancer patients are small (< 1 cm) and hardly visible or palpable at the time of operation. In fact, nearly 80% of nodal tumor metastases are found in lymph nodes <5 mm in maximal dimension and are easily overlooked at the time of operation or pathologic evaluation.32,33,34,35 Nodes are generally considered to be normal if they are smaller than 1 cm2. The consistency of nodes upon palpation may also be illustrative; for example, stony-hard nodes typically suggest cancer metastasis. Similarly, a group of mesenteric nodes that appear to be connected or move as a unit, called “matted” nodes, are consistent with lymphatic spread of disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree