Chapter 48 Colon Cancer

Etiology and Epidemiology

In 2011 the American Cancer Society estimated that 141,210 patients were diagnosed with colorectal cancer and 49,380 deaths occurred.1 Although this malignancy may be linked to chemical carcinogens within the bowel lumen, it is not established whether these are ingested, the result of chemical activation of substances in the fecal stream, or a bacterial byproduct.2 Environmental and dietary factors have been established as contributing to colorectal cancer. Factors shown to increase the risk of developing this disease include increasing age, race, male sex, family history of colorectal cancer, increasing height, increasing body mass index, processed meat intake, excessive alcohol intake, and low folate consumption. Of these risk factors, only increasing age, male sex, and excessive alcohol use have been found to be associated with rectal cancer.3 The value of consumption of fruits and vegetables in the prevention of colon and rectal cancer remains controversial, although some studies have suggested that these associations have been overstated.4 Contemporary prospective and randomized data do not support a high fiber diet in the prevention of colorectal cancer.5 Other studies have suggested that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may reduce the risk of colorectal cancer. The role of chemopreventive agents (carotenoids, polyamine inhibitors, aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) in colorectal cancer is under active investigation.

Prevention and Early Detection

Neoplastic polyps, including tubular adenomas, villous adenomas, and tubulovillous adenomas, are precursors of colon cancers. Most colorectal cancers arise from preexisting polyps.6 Patients with neoplastic polyps should be considered at high risk for large bowel cancer, and polypectomy may reduce this risk. With the availability of the flexible colonoscope and endoscopic polypectomy, polyps can be removed at a premalignant stage and patients observed closely.

Screening

Because the cumulative lifetime risk of developing colorectal cancer in the United States is about 6%,7 screening programs for the general population have been undertaken. The goal of screening is to detect preinvasive polyps or early invasive cancer. The presence of polyps increases the risk for cancer to approximately 15%. Data from programs in which proctoscopy is performed annually suggests that routinely scheduled polypectomy reduces the development of subsequent bowel cancer by 80% or more.2 The American Cancer Society has recommended that screening begin at age 50 in the average risk patient by (1) annual fecal occult blood test, fecal immunochemical test, and/or flexible sigmoidoscopy every 5 years; (2) double-contrast barium enema every 5 years; (3) colonoscopy every 10 years; or (4) CT colonography every 5 years. The interval for stool DNA tests has not been firmly established. Intensive surveillance is recommended for patients at high risk (patients with adenomatous polyps, history of colorectal cancer, a first-degree relative diagnosed with colorectal cancer or adenomas, inflammatory bowel disease, or high risk because of family history or genetic testing). CT colonography as well as genetic fecal testing continue to be studied as potential screening tools. Although screening methods can detect colorectal cancer at an early stage, less than 40% of patients are diagnosed with early disease, likely reflecting low rates of disease awareness as well as the infrequency of screening in eligible candidates.7,8

Biologic Characteristics/Molecular Biology

Microsatellites are mutated short-repeat DNA sequences usually consisting of one to five nucleotides. Microsatellite “instability” is found in a majority of patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) as well as a minority of patients with sporadic colorectal cancers. It has been shown that this instability occurs in patients with mutations in genes encoding enzymes that repair DNA replication errors. These defects in mismatch repair lead to high-frequency microsatellite instability. Studies have suggested that patients with tumors possessing a high-frequency of microsatellite instability have a more favorable outcome and develop fewer metastases.9 Further elucidation of the genetic pathways in the development of colorectal cancer remains an active area of investigation and may ultimately impact therapy for this disease.

Clinical Manifestations, Patient Evaluation, and Staging

The clinical presentation of colon cancer is determined largely by site of the tumor. Cancers of the right colon are often exophytic and commonly associated with iron-deficiency anemia owing to occult blood loss. During the past 20 years the relative incidence of cancer of the right colon has increased and accounts for one third of cancers of the large bowel. Many of these are diagnosed late.2 Cancers of the left colon and sigmoid colon are often deeply invasive, annular, and accompanied by obstruction and rectal bleeding.

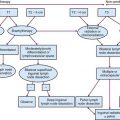

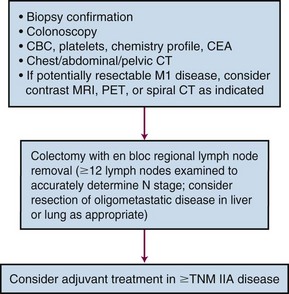

For patients undergoing resection, preoperative evaluation should include pathologic confirmation of adenocarcinoma, colonoscopy to evaluate the extent of tumor and rule out synchronous primary tumors (occurring in 3% to 5%), baseline blood cell counts with liver function tests, and carcinoembryonic antigen levels. Patients should undergo chest, abdominal, and pelvic CT to evaluate the extent of locoregional disease as well as the presence or absence of distant metastases. PET, MRI, and ultrasonography may be useful in evaluating patients with oligometastatic disease who may be appropriate candidates for resection of metastatic disease with curative intent. A diagnostic algorithm of the management of patients with potentially resectable colon cancer is shown in Figure 48-1.

Figure 48-1 Diagnostic algorithm of the management of patients with potentially resectable colon cancer.

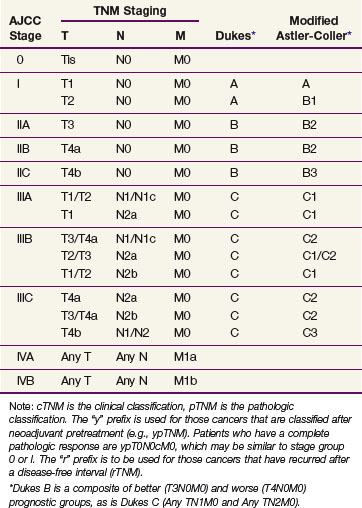

Prognostic factors influencing survival in colon cancer patients include depth of tumor invasion into and beyond the bowel wall, the number of involved regional lymph nodes, as well as the presence or absence of distant metastases. The TNM system of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) can be used as a clinical (preoperative) or postoperative staging system (Tables 48-1 and 48-2). Additionally, site-specific prognostic factors have been identified and included in the AJCC staging (Table 48-3).

TABLE 48-1 American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM Staging for Colorectal Cancer (2010)

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Primary Tumor (T) | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial or invasion of lamina propria |

| T1 | Tumor invades submucosa |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria |

| T3 | Tumor invades through the muscularis propria into pericolic tissues |

| T4a | Tumor penetrates to the surface of the visceral peritoneum* |

| T4b | Tumor is adherent to or directly invades other organs or structures*,† |

| Regional Lymph Nodes (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Metastasis in one to three regional lymph nodes |

| N1a | Metastasis in one regional lymph node |

| N1b | Metastasis in two to three regional lymph nodes |

| N1c | Tumor deposit(s) in the subserosa, mesentery, or nonperitonealized pericolic or perirectal tissues without regional nodal metastasis |

| N2 | Metastasis in four or more regional lymph nodes |

| N2a | Metastasis in four to six regional lymph nodes |

| N2b | Metastasis in seven or more regional lymph nodes |

| Distant Metastasis (M) | |

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed. |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

| M1a | Metastasis confined to one organ or site (e.g., liver, lung, ovary, nonregional node) |

| M1b | Metastases in more than one organ/site or the peritoneum |

Note: A satellite peritumoral nodule in the pericolorectal adipose tissue of a primary carcinoma without histologic evidence of residual lymph node in the nodule may represent discontinuous spread, venous invasion with extravascular spread (V1/2), or a totally replaced lymph node (N1/2). Replaced nodes should be counted separately as positive nodes in the N category, whereas discontinuous spread or venous invasion should be classified or counted in the site-specific factor category of Tumor Deposit (TD).

* Direct invasion in stage T4 includes invasion of other organs or segments of the colorectum by way of the serosa, as confirmed by microscopic examination (e.g., invasion of the sigmoid by a carcinoma of the cecum). For cancers in a retroperitoneal or subperitoneal location, direct invasion involves other organs or structures by virtue of extension beyond the muscularis propria (e.g., a tumor on the posterior wall of the descending colon invading the left kidney or lateral abdominal wall or a mid or distal rectal cancer with invasion of the prostate with invasion of the prostate, seminal vesicles, cervix or vagina).

† Tumor grossly adherent to other organs or structures is classified as cT4b. However, if no tumor is present in the adhesion microscopically, the classification should be pT1 to pT4a depending on the anatomic depth of wall invasion. The V and L classifications should be used to identify the presence or absence of vascular or lymphatic invasion where the pN site-specific factor should be used for perineural invasion.

From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, editors: Colon and rectum. In American joint committee on cancer staging manual, ed 7, New York, 2010, Springer.

TABLE 48-3 Site-Specific Prognostic Factors for Colorectal Cancer

From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, editors: Colon and rectum. In American joint committee on cancer staging manual, ed 7, New York, 2010, Springer.

Primary Therapy

Surgery

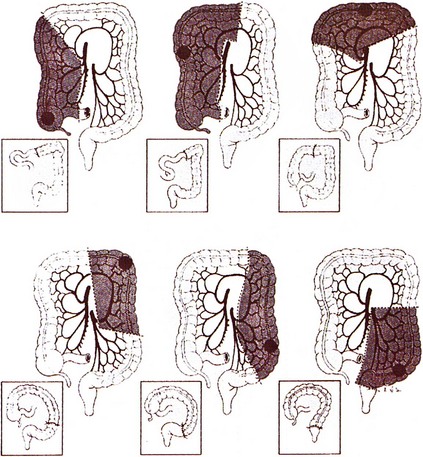

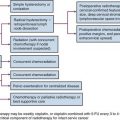

Surgery remains the primary treatment of colonic tumors. Resection with curative intent is possible in approximately 75% of patients.2 Surgical resection of primary colon cancer is based on the anatomy and mechanisms by which this disease spreads. Adenocarcinomas of the colon may grow by direct extension into the lymphatics of the submucosa and bowel wall. To avoid cutting across tumor in intramural lymphatics, sufficient lengths of bowel must be resected proximal and distal to the primary cancer. Colon cancer often extends through the serosa into mesenteric lymphatics that run along the blood vessels draining into the portal watershed at the root of the mesentery. Resection includes removal of the major lymphatic drainage system in the mesentery. Because anatomic resections designed to include named blood vessels also include the draining lymphatics, the boundaries for resecting large bowel cancer are relatively uniform (Fig. 48-2). Right hemicolectomy, transverse colectomy, left hemicolectomy, and sigmoid resection are performed by adherence to surgical oncologic principles without major sacrifice of large bowel function.