CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF HYPOOSMOLALITY

Hypoosmolality is associated with a broad spectrum of neurologic manifestations, ranging from mild nonspecific symptoms (e.g., headache, nausea) to more significant disorders (e.g., disorientation,

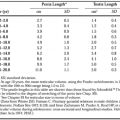

confusion, obtundation, and seizures). In the most severe cases, death can result from respiratory arrest after tentorial cerebral herniation and brainstem compression. This neurologic symptom complex has been termed hyponatremic encephalopathy and primarily reflects brain edema resulting from osmotic water shifts into the brain because of decreased effective plasma osmolality. Significant symptoms generally do not occur until the serum [Na+] falls below 125 mEq/L, and the severity of symptoms can be roughly correlated with the degree of hypoosmolality4 (Fig. 27-3). Individual variability is marked, however, and for any single patient, the level of serum [Na+] at which symptoms appear cannot be predicted with great accuracy. Furthermore, several factors other than the severity of the hypoosmolality also affect the degree of neurologic dysfunction. Most important is the period over which hypoosmolality develops. Rapid development of severe hypoosmolality is frequently associated with marked neurologic symptoms, whereas gradual development over several days or weeks is often associated with relatively mild symptomatology despite profound degrees of hypoosmolality. This is because the brain can counteract osmotic swelling by excreting intracellular solutes (including potassium4 and organic osmolytes22), an adaptive process known as volume regulation.21 Because this is a time-dependent process, rapid development of hypoosmolality can result in brain edema before this adaptation occurs, but with slower development of the same degree of hypoosmolality, brain cells can lose solute sufficiently rapidly to prevent brain edema and neurologic dysfunction.42 This accounts for the much higher incidence of neurologic symptoms as well as higher mortality rates in patients with acute hyponatremia than in those with chronic hyponatremia.4 A striking example of this is the fact that the most dramatic cases of death due to hyponatremic encephalopathy have generally been reported in postoperative patients,43 in whom hyponatremia can develop rapidly as a result of postoperative retention of hypotonic fluid infusions.

confusion, obtundation, and seizures). In the most severe cases, death can result from respiratory arrest after tentorial cerebral herniation and brainstem compression. This neurologic symptom complex has been termed hyponatremic encephalopathy and primarily reflects brain edema resulting from osmotic water shifts into the brain because of decreased effective plasma osmolality. Significant symptoms generally do not occur until the serum [Na+] falls below 125 mEq/L, and the severity of symptoms can be roughly correlated with the degree of hypoosmolality4 (Fig. 27-3). Individual variability is marked, however, and for any single patient, the level of serum [Na+] at which symptoms appear cannot be predicted with great accuracy. Furthermore, several factors other than the severity of the hypoosmolality also affect the degree of neurologic dysfunction. Most important is the period over which hypoosmolality develops. Rapid development of severe hypoosmolality is frequently associated with marked neurologic symptoms, whereas gradual development over several days or weeks is often associated with relatively mild symptomatology despite profound degrees of hypoosmolality. This is because the brain can counteract osmotic swelling by excreting intracellular solutes (including potassium4 and organic osmolytes22), an adaptive process known as volume regulation.21 Because this is a time-dependent process, rapid development of hypoosmolality can result in brain edema before this adaptation occurs, but with slower development of the same degree of hypoosmolality, brain cells can lose solute sufficiently rapidly to prevent brain edema and neurologic dysfunction.42 This accounts for the much higher incidence of neurologic symptoms as well as higher mortality rates in patients with acute hyponatremia than in those with chronic hyponatremia.4 A striking example of this is the fact that the most dramatic cases of death due to hyponatremic encephalopathy have generally been reported in postoperative patients,43 in whom hyponatremia can develop rapidly as a result of postoperative retention of hypotonic fluid infusions.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree