Fig. 6.1

A squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue showing the indurative type of observational findings and the endophytic type of clinical growth pattern

Fig. 6.2

A squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue showing the ulcerative type of observational findings and the endophytic type of clinical growth pattern

Fig. 6.3

A squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue showing the granular type of observational findings and the exophytic type of clinical growth pattern

Fig. 6.4

A squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue showing the leukoplakic type of observational findings and the superficial type of clinical growth pattern

Fig. 6.5

A squamous cell carcinoma of the tongue showing the papillary type of observational findings and the exophytic type of clinical growth pattern

Recently, a more universal and reproducible classification based on clinical growth patterns judged by close inspection and digital palpation has been proposed, which divides oral cancer into three types: superficial, exophytic, and endophytic [11]. These superficial, exophytic, and endophytic types are leukoplakic or erythroplakic lesions lacking deep indurations (Fig. 6.4), granular or papillary lesions with moderately deep indurations (Figs. 6.3 and 6.5), and indurative or ulcerative lesions with extensive deep indurations (Figs. 6.1 and 6.2), respectively. Especially in carcinoma of the tongue, the endophytic type is more closely associated with poor prognosis in comparison with the other types. This classification thus provides clinically useful information as a prognostic factor for recurrence, metastasis, and survival rate.

In addition to macroscopic inspection and digital palpation, pathological examination is indispensable for definite and accurate evaluation of lesions. Cancer tissue together with adjacent noncancerous mucosa is generally sampled using wedge resections as biopsy specimens. The objective of a biopsy is not only to make a definitive diagnosis of cancer but also to obtain detailed information concerning the degree of histological malignancy, mode of invasion, stage of invasion, vascular invasion, cellular response, and probability of lymph node metastasis.

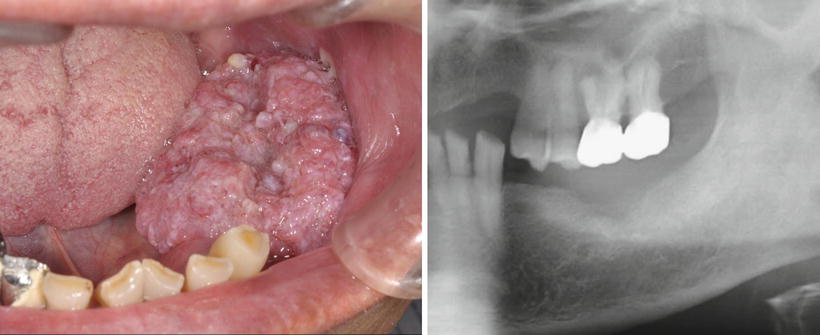

Furthermore, oral cancers should be evaluated using imaging with X-ray examinations including pantomography, CT, MR, ultrasonography, and PET. X-ray examinations, CT and MR, are extremely supportive to identify the invasion of adjacent tissues by attaching importance to the evaluation of depth. Furthermore, bone resorption patterns identified using imaging provide clinically useful information to evaluate malignancy of oral cancers. The patterns are usually classified into two types: pressure and moth-eaten types [11]. The pressure type shows flat, saucer-shaped, or U-shaped margin and is observed in association with slowly growing and noninvasive lesions (Fig. 6.6). In contrast, the moth-eaten type is irregular with an indistinct margin and is closely associated with rapidly growing and highly invasive lesions (Fig. 6.7).

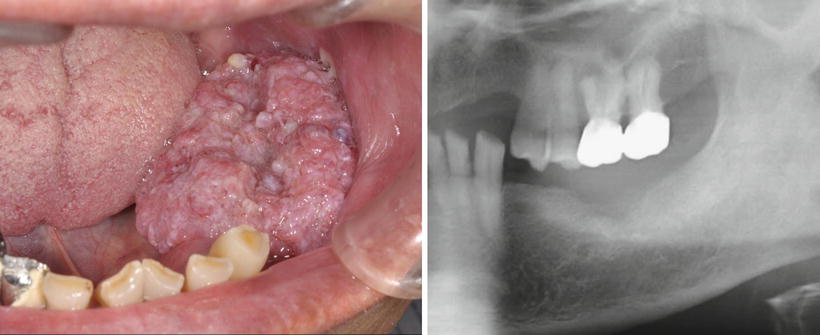

Fig. 6.6

A squamous cell carcinoma of the lower gingiva showing the granular type of observational findings, the exophytic type of clinical growth pattern, and the pressure type of bone resorption

Fig. 6.7

A squamous cell carcinoma of the lower gingiva showing the indurative type of observational findings, the endophytic type of clinical growth pattern, and the moth-eaten type of bone resorption

Cervical lymph node metastasis should be evaluated using CT and ultrasonography, as well as careful digital palpation, since approximately 30 % of oral cancers metastasize to the regional lymph node(s) in the ipsilateral and/or contralateral neck. MR and PET are occasionally supportive. Distant metastasis is identified only in approximately 1 % of oral cancers, but should be routinely evaluated using chest X-ray examination, as lung is one of the most frequent distant organs to which oral cancers metastasize. 67Ga and bone scintigraphies, and recently PET, are useful to identify distant metastasis to other organs.

6.1.1.2 Site-Specific Clinical Characteristics of Oral Cancers

Buccal Mucosa

In the Indian subcontinent, oral cancers account for more than one third of all malignancies, and buccal mucosa is the most common site for them. This is probably related to the widespread habit of betel- and tobacco-chewing. Carcinomas of the buccal mucosa account for approximately 10 % of oral cancers. The tumors usually involve the mucosa opposite the lower third molar tooth and retromolar pad and are predominantly well and moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinomas.

The early lesion is painless and may form a white or speckled patch or an indurated nodule or ulcer. As the tumor enlarges exophytically, it usually becomes ulcerated or papillary and then invades into the surrounding muscle and bones (Figs. 6.8 and 6.9). Nodal involvement, usually in the jugulodigastric, submandibular or upper deep cervical lymph nodes, is seen in 35–50 % of patients.

Fig. 6.8

A squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa showing the ulcerative type of observational findings and the endophytic type of clinical growth pattern

Fig. 6.9

A squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa showing the papillary type of observational findings and the exophytic type of clinical growth pattern

Upper Alveolus and Gingiva

Carcinomas of the upper alveolus and gingiva account for approximately 10 % of oral cancers, and the incidence is apparently lower than that of carcinomas of the lower alveolus and gingiva. These carcinomas are commonly well and moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinomas.

The tumor may present as a lump or as a more obvious vegetating mass and tends to involve the bone at a relatively early stage. Bone resorption patterns classified into either pressure or moth-eaten type provide clinically useful information to evaluate the malignancy of the tumor. The speckled appearance of the granular and exophytic mass is most frequently seen and the ulcerated mass is also seen (Fig. 6.10). If teeth are present in relation to the tumor, they may become loose, painful, and periostitic. Carcinomas of the maxillary sinus and malignant lymphomas invade the alveolus and/or palate to present in a similar manner. The submandibular and upper deep cervical lymph nodes are the most frequent sites of secondary spread and nodal involvement is evident in 20–30 % of patients.

Fig. 6.10

A squamous cell carcinoma of the upper alveolus showing the granular type of observational findings and the exophytic type of clinical growth pattern

Lower Alveolus and Gingiva

Carcinomas of the lower alveolus and gingiva account for as many as 20 % of oral cancers, and the incidence is two times higher than that of carcinomas of the upper alveolus and gingiva. The carcinomas are pathologically squamous cell carcinomas with high or moderate differentiation.

The tumor is most commonly granular and exophytic and may be indurative, ulcerative, or papillary, while the leukoplakic type is less commonly presented (Figs. 6.6, 6.7, and 6.11). As carcinomas of the upper alveolus and gingiva, the tumor frequently involves the bone at a relatively early stage, and bone resorption patterns, either pressure or moth-eaten type, provide clinically useful information to evaluate the malignancy of the tumor. If teeth are present in relation to the tumor, they may become loose, painful, and periostitic. Once the tumor invades into a mandibular canal, anesthesia of the lower lip is quite commonly detected, which may be accompanied by a pathologic fracture of the mandible. Metastasis of the tumor to regional lymph nodes, particularly submandibular and submental lymph nodes, is more frequently evident than that of carcinomas of the upper alveolus and gingiva, and the incidence is 30–40 % of patients.

Fig. 6.11

A squamous cell carcinoma of the lower alveolus showing the ulcerative type of observational findings and the endophytic type of clinical growth pattern

Hard Palate

Carcinomas of the palate are rare and account for approximately 3 % of oral cancers, but are fairly common in countries where reverse cigarette smoking is practiced. Most of them are highly differentiated squamous cell carcinomas. It should be noted that the most common site of intraoral salivary gland tumors is also the palate. The incidence of carcinomas of the palate is almost the same as that of salivary gland malignancies in the palate. Furthermore, it is occasionally difficult to distinguish it from a carcinoma of the maxillary sinus that has spread to the palate.

The tumor is often ulcerative or papillary and usually spreads extensively before it affects the bone (Fig. 6.12). The incidence and mode of lymphatic metastasis is almost the same as that of carcinomas of the upper alveolus and gingiva, but lymphatic spread rarely occurs to the retropharyngeal group of nodes.