Definition

The Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) in its Local clinical audit: handbook for physicians describes clinical audit as ‘an approach to quality improvement based on clinical data collected by clinicians, to support the work of clinicians in improving the quality of care for patients.

Clinical audit is, first and foremost, a professional and clinical tool, not a management or regulatory tool. The General Medical Council (GMC) guidance requires all doctors to seek to improve the quality of care. Clinical audit provides a method for achieving such improvement’.3

Clinical audit has many definitions. One definition, internationally recognized and endorsed by the HQIP, comes from the Principles of Best Practice in Clinical Audit.4

Clinical audit is a quality improvement process that seeks to improve patient care and outcomes through systematic review of care against explicit criteria and the implementation of change. Aspects of the structure, process and outcomes of care are selected and systematically evaluated against explicit criteria. Where indicated, changes are implemented at an individual, team, or service level and further monitoring is used to confirm improvement in healthcare delivery.

The following chapter will expand on the components of this definition.

Background

Clinical Audit and Quality of Healthcare

Professor Avedis Donabedian introduced the modern era of clinical audit with his seminal works in the 1960s–1980s.5, 6 He introduced a rigorous approach to improving quality in healthcare and developed the concept of measuring structure (what is needed to provide a good service), process (what is done to provide a good service) and outcome (what is expected of a good service) as key elements to evaluating quality of care. In the 1980s Royal Colleges were promoting medical audit as part of good professional practice. Over time, medical audit became clinical audit, recognizing that care is a multidisciplinary process, but audit remained a local activity with modest impact on the service.

In 1997, the new Labour Government introduced a sea change in the role of quality management in the NHS with the White Papers, The new NHS; modern and dependable, and A first-class service: quality in the new NHS. Quality of care was no longer to be the preserve of individual professionalism but became a matter of management responsibility. The government sought to improve the quality of healthcare by:

- Continual improvement in the overall standards of clinical care;

- Reducing unacceptable variations in clinical practice;

- The best use of resources so that patients receive the greatest benefit.

These aims were to be achieved by:

- Setting, delivering and monitoring quality standards;

- Making quality of care a management responsibility rather than just a professional commitment.

To execute these changes the government established bodies and programmes as indicated in Table 138.1.

Table 138.1 National developments to implement the quality agenda in healthcare–1997.

Setting standards

|

Delivering improvements in care

|

Monitoring standards

|

In 2008, the government White Paper, High Quality Care for All, authored by Lord Darzi, built on the undoubted success of bodies such as the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) and the Healthcare Commission in setting standards, monitoring standards and laying the foundation for improved patient care. The White Paper re-emphasized the importance of measuring performance, benchmarking and the use of data to drive change.1

In 2010 the White Paper, Equity and excellence: Liberating the NHS, provided the new Coalition Government vision for how the changes introduced in 1998 and reinforced by Lord Darzi could be developed further. The role of national audit was strongly endorsed with two particular changes of emphasis:2

Organizational process targets would be downgraded and the emphasis would be on measures of clinical performance that are directly linked the improved health outcomes.

Quality of healthcare can be broken down into ‘domains’. Donabedian proposed two domains: technical quality of care and interpersonal quality of care. More recently the Institute of Health Improvement have proposed widening the concept to include six domains, namely: safety, effectiveness, patient centredness, timeliness, efficiency and equity.7 Lord Darzi in High Quality Care for All emphasizes the importance of safety, effectiveness and the patient experience.1

National Clinical Audit

National audits have demonstrated over time how clinical audit can provide valuable information to address these domains of quality and contribute to improved service provision and patient care. National clinical audits, such as that of stroke8 and myocardial infarction9 have demonstrated the great variation in care in hospitals around the country as well as the dramatic changes and improvements in practice that have occurred over time. Data from such audits have had a significant impact on the formulation of national policy for developing services as well as providing local teams with invaluable data with which to seek improvements in care at a local level.

In addition to contributing to improving healthcare, national clinical audits serve other roles including providing a basis for research, education and revalidation.

Local Clinical Audit

Local clinical audit, while being routinely incorporated into the work requirements of trained doctors and doctors in training, has struggled to maximize its potential. In 2008 the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership was commissioned by the Department of Health to not only manage the national clinical audit programme, but also to re-invigorate local audit. The Partnership has initiated many projects to enhance local audit and has provided a much needed champion for all those involved in local audit.

Within the medical specialities, specialist societies have advanced their commitment to clinical audit, seeking to coordinate work, and provide web-based data collection systems to facilitate multisite local audit. Societies such as the British Thoracic Society have been in the vanguard of these developments. Such approaches will help all clinicians maximize the use of local clinical audit for the benefit of patients.

The Audit Cycle

Planning an Audit

Identifying What is to be Reviewed

It is sensible, for pragmatic reasons and on the basis of the research evidence relating to effective clinical audit, to focus on topics where there is a perceived inadequacy or variation in patient care or service provision. Professionals with specialized areas of interest may wish to perform an audit of local practice. Audit may be used as part of the clinical governance mechanism to explore aspects of care where there are concerns over the quality of care or where there have been significant numbers of complaints.

The value of an audit can be enhanced if the topic to be evaluated is important to several or many sites. It may be possible, either on a regional basis or via a specialist society, to coordinate the audit over a number of sites so that the data can be used to ‘benchmark’ local performance against that achieved by peers elsewhere in the country.

Commitment to Audit

The recommendations of the Bristol Inquiry emphasized the importance of clinical audit within the system of local monitoring of performance and the need for trusts to fully support such activity—including access to time, facilities, advice and expertise.10 These recommendations, welcomed by the government, echo the findings of systematic review, that clinical audit will only be successful if it is adequately resourced and it becomes part of routine practice.

Commitment is not just a clinical matter. It is essential that healthcare organizations as a whole seriously embrace these recommendations so that when results are available clinicians and managers are both willing to respond and jointly plan appropriate changes.

The planning phase needs to look ahead to how the conclusions will be used. This ranges from the need to include variables that allow for useful interpretation of the results as well as quality considerations to ensure the results are valid and reliable. The huge potential of audit for improving care can only be realized if the outcomes of each study are accepted as valid by all parties and thus utilized as the basis for reviewing and adapting practice.

Skills for Carrying out Audit

The infrastructure required includes access to skilled personnel (with dedicated time for the project) to carry out the work and systems to facilitate audit. Expertise is required in establishing a sound methodology for the work (see the following text) including an understanding of such issues as the size of population required for study, identifying relevant data for collection, the reliability and feasibility of data collection, data analysis, data presentation and implementation of change. Even apparently simple tasks such as setting out a questionnaire are in practice quite difficult. Poorly phrased or ambiguous questions result in data that cannot be interpreted. Therefore, most projects should be performed in conjunction with non-clinical staff with experience and expertise both in the technical aspects and in project management. They need support from professional healthcare workers to ensure the clinical acceptability and credibility and hence the validity of the study. At a local level, clinical teams should, therefore, work with clinical audit departments to ensure issues of methodology and project management are properly addressed. For national clinical audit significant investment in such audit infrastructure is required to ensure effective project delivery.

A multidisciplinary team is required that can effectively oversee and provide advice on the planning, carrying out and dissemination of the results of audit work. The group should include user involvement.

Modern audit has been made possible by the widespread availability of computing systems. They include software that can facilitate data collection, code and encrypt patient identifiable data and do sophisticated analysis. Access to such resources and expertise will enhance the audit process.

Patient and User Input

Health services exist to serve the public and any assessment of care quality should include patient and users as full partners at all stages of the assessment process. Feedback from service users may shed a useful light on where services are inadequate, and also on the users’ perspective of what is important as opposed to the views of management and professionals. Kelson has provided useful advice as to how user involvement can be achieved.11

As well as involving patients in the setting up and running of audits it is increasingly important to ensure that audit evaluates care from the perspective of the patient or user.12, 13 The patient perspective can be measured in terms of:

These measures provide a global assessment of the healthcare received [process] or the outcomes of care [outcomes] from the patient perspective. Such measures are helpful in monitoring trends but are very non-specific and provide no insight into the cause of any inadequacy of care.

These gather more specific feedback from patients with regard to the process of care received. These do provide an insight into where deficiencies in service provision lie from the patient perspective. Such measures are useful for assessing care for patients with chronic conditions.

Such measures are currently much in vogue. There is a disease-specific component and a global component that measure the patient’s perception of their health status following an intervention. Currently such measures are developed and in use in the NHS for surgical procedures, for example hip surgery, varicose veins surgery, hernia repair and cataract surgery. PROMs for more medical conditions are in the process of being developed.

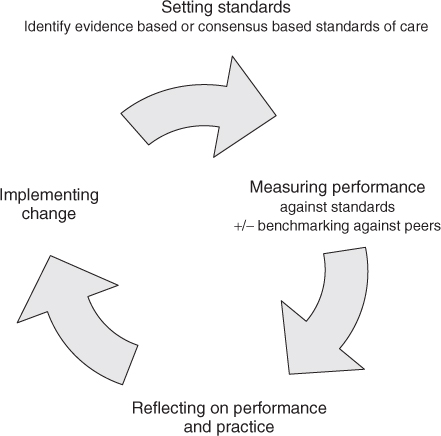

Determining Standards

As indicated in Figure 138.1, explicit standards of best practice must be established against which to audit. The important first step is to establish a statement or statements of the level of practice against which healthcare is to be assessed. There are two approaches: (1) define a gold standard and assess against that absolute target, or (2) collect comparative data and assess relative performance against the benchmark created by what one’s peers are doing. In theory, the gold standard is preferred but often the evidence needed to set that standard is lacking. Furthermore, gold standards can rarely command 100% compliance, for example the Coronary Heart Disease NSF (National Service Framework) target for 30 minutes ‘door to needle’ for thrombolysis was set at 75% to allow, for example, for those where diagnosis was delayed.9

Evidence-Based Standards

Where possible, such statements of best practice should be derived from evidence-based research. The process calls for careful attention to literature searching, critical appraisal and peer review. The methods used by such bodies as the Cochrane Collaboration, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN), and the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) all ensure a high degree of credibility in the recommendations derived. Evidence-based audit standards can be determined from such recommendations.

Example: The NICE Clinical Guideline on ‘Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease’ (COPD) has as an evidence-based recommendation that ‘The presence of airflow obstruction should be confirmed by performing spirometry. All health professionals managing patients with COPD should have access to spirometry and be competent in the interpretation of the results’.14 The audit criterion proposed to complement the recommendation is: ‘Percentage of patients with a diagnosis of COPD who have had spirometry performed’.

The role of NICE is becoming increasingly important in not only developing guidelines but also in producing associated quality standards.

Consensus-Based Standards

Where it is not possible to obtain evidence-based standards consensus techniques should be used.15 These will enable the best opinion of current health practice to be determined. The challenge in such a process is to ensure that there is no bias due to individual personalities or professions and to ensure that the views of all interested parties are included. Approaches include the following:

Selection of Gold Standard

In practical terms, healthcare settings will need to determine what aspect of care they wish to audit. They will then need to seek the most appropriate standard(s) against which to audit, which has the authority of being derived from one of the approaches above.

Determining Audit Criteria

The Donabedian principle of measuring structure, process and outcome remains the basis for selecting the type of audit criteria.

Structure

Measures of the facilities and resources available to a healthcare setting will reflect the potential to provide high-quality care. It is difficult for staff to provide a high-quality service unless they have the resources to do it. Equally, it has to be recognized that high-class care is not guaranteed in premium facilities. Facilities have to be matched with staff who are provided with training and the expertise to carry out the appropriate care.

Example: For coronary heart disease, if a hospital does not have access to immediate coronary angiography it is not possible to provide the highest quality care for people with acute coronary syndromes.

Measures of ‘structure’ can include facilities, staffing levels, skill mix, access to training, standard use of protocols, mechanisms for advice and information for patients and relatives. Data relating to ‘structure’ are the easiest of the audit measures to obtain. Such data form the basis of accreditation schemes and systems of this type are widely used internationally and in some parts of the United Kingdom as an indication of service quality.

Process

Audit criteria of ‘process’ explicitly define key aspects of care that should be provided if high-quality care is to be achieved. Aspects of process measured may include the history, examination, investigation, treatment and follow-up care. The process may also include the involvement of carers. Processes of care need to be clearly defined to ensure reliable comparison between different sites and different data collection episodes.

Example: In stroke care, a swallow assessment is important as a process. The audit has to define what constitutes an appropriate swallow assessment and what detail within the records reliably reflects what was carried out. Process data may be collected retrospectively by reviewing a selected number of cases. Such an approach has significant problems in ensuring that there is no selection bias in the notes that are retrieved. A planned retrospective audit such as the National Sentinel Audit of Stroke8 (assessing the care of 40 consecutive stroke patients in all hospitals in England, Wales and Northern Ireland) reduces the risk of bias. An alternative, but organizationally more challenging, approach is to obtain prospective data with data collection part of routine practice as in the Myocardial Infarction National Audit Project (MINAP).9 In practice, measurement of process provides a useful reflection of whether care matches up with expected best practice. Data related to process can be more difficult to retrieve than measures of structure but tend to be easier to collect than outcome measures and have the added benefit that they are not dependent on case mix. Structure, process and outcome are all interrelated. Data from the National Stroke audit has demonstrated that settings where good structures are in place presage better processes of care and lead to better outcomes. It is rarely apparent, however, at the outset, which will be the most sensitive measures. Increasing clinical audit experience will help provide an indication of the structures and processes that are important in determining high-quality care. There are problems, however. If specific processes are identified as the markers for quality, departments and services wishing to be seen to provide high-quality care may concentrate purely on the selected process to the detriment of overall care.

Outcomes

Ideally, the quality of healthcare should be evaluated by the outcomes it achieves.

Example: For urinary incontinence, does appropriate assessment and treatment of patients result in a reduction in the prevalence of incontinence?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree