Cancer staging systems have been designed to provide both physicians and patients with a metric for assessing the extent of disease and prognosis. Staging systems provide a universal classification that describes the extent of disease. This classification impacts individual stage-specific treatment, the development of practice guidelines, and the design of clinical research/trials. Cancer staging is therefore the foundation on which all clinical cares are based and is essential for the rigorous study of cancer therapies.

For most cancers, staging is predicated on the pathologic (postoperative) assessment of the tumor which is dependent on gross and histologic findings from the surgical specimens. For cancers in which presurgical (neoadjuvant) therapy is utilized, an additional clinical (preoperative) staging system is required. In pancreatic cancer, the clinical stage is determined by the biochemical, radiographic, and physical examinations of the patient, and is defined by the tumor–vasculature relationship. The accuracy of clinical staging has revolutionized the management of pancreatic cancer, which historically used operative staging to determine resectability. Prior to the use of modern imaging techniques, up to 30% of patients with presumed resectable pancreatic cancer were found, at the time of operation, to have either metastatic disease or vascular invasion which precluded resection of the pancreatic tumor.1 The limitation of operative staging is that patients who have advanced unresectable disease experience a delay in the receipt of the best appropriate therapy (chemotherapy and/or chemoradiation) secondary to the surgical procedure and the necessary postoperative recovery. In addition, laparotomy may potentially negatively impact the tumor–host relationship in favor of tumor progression, as the effect of surgery has been associated with relative immune compromise.

In pancreatic cancer, the use of neoadjuvant therapy is an alternative to a surgery-first approach for localized disease. Neoadjuvant therapy provides systemic therapy earlier in the treatment sequence and is the preferred approach in patients with borderline resectable or locally advanced disease.2 Even among patients with early-stage (resectable) pancreatic cancer who receive curative resections, the high rate of disease recurrence suggests that radiographically occult disease exists at the time of surgery in most patients. Although multiple randomized controlled trials3–5 have demonstrated a survival benefit for patients who receive adjuvant systemic chemotherapy after pancreatectomy, at least 50% of patients fail to recover from surgery to complete adjuvant therapy.6 Additional advantages of a neoadjuvant strategy include (1) early treatment of presumed micrometastatic disease, (2) the ability to minimize stage misclassification by providing a time interval during which indeterminate lesions (which may be metastases) may be better characterized through serial radiographic imaging, and (3) the theoretical efficacy of radiation in nonhypoxic environment.

For pancreatic cancer, a clinical staging system has been developed that uses precise, objective, anatomic criteria to determine the extent of the tumor–vasculature relationship and guides the selection of neoadjuvant therapy. Clinical/radiographic staging performed prior to any therapy and over serial time points can provide important insights into tumor biology, response to therapy, and can more accurately predict the utility of surgical resection. This chapter focuses on the clinical/radiographic definitions of pancreatic cancer staging and key modalities used to determine stage, as well as the importance of the pathologic review and staging of the resected specimen.

Determination of clinical staging is based on clinical and radiographic data. This includes evaluation of tumor resectability based on imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and positron emission tomography (PET), as well as incorporating staging laparoscopy with cytology and biomarkers such as CA 19-9. TNM staging can be estimated based on these criteria, but will be discussed more in depth in our discussion on pathologic staging.

Although consensus among clinicians may not exist, all published guidelines generally agree upon two clinical stages of operable disease (resectable and borderline resectable) and two clinical stages of inoperable disease (locally advanced disease and metastatic), which are summarized in Table 139-1. At the Medical College of Wisconsin, resectable pancreatic cancer (Fig. 139-1) is defined by an absence of tumor extension to the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), celiac axis, or hepatic artery (HA). Lack of arterial abutment is characterized by the presence of normal soft tissue planes between the tumor and the adjacent arteries. Associated superior mesenteric vein/portal vein (SMV/PV) abutment/encasement may be acceptable for resection provided that adequate inflow and outflow targets are identified for potential venous reconstruction. The distinction between borderline resectable (Fig. 139-2) and locally advanced pancreatic cancers (Fig. 139-3) is determined by the degree of tumor–artery interface (abutment is defined as <180° and encasement is >180°). As the tumor–artery interface increases from abutment to encasement, a complete gross resection of all disease is likely not possible—therein lies the rationale for the distinction between borderline resectable and locally advanced disease. The borderline resectable category also includes tumor abutment/encasement of a short segment of the hepatic artery—usually at the origin of the gastroduodenal artery (GDA), or an occluded SMV/PV that may be amenable to reconstruction. When occlusion of the SMV/PV prohibits the technical option for reconstruction (due to an inadequate SMV caudal to the area of occlusion or an inadequate portal vein cephalad to the site of occlusion), the tumor is considered locally advanced. Finally, metastatic disease is defined by the presence of extrapancreatic metastases (on radiographic imaging, biopsy is usually not required). These criteria have been adopted with slight modification (Table 139-2) by multiple institutions and by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) oncology guidelines which differ slightly from the precise CT criteria used at our institution.2

Definition of Resectability Used by the Multidisciplinary Pancreatic Cancer Working Group at the Medical College of Wisconsin

| Resectable | |

| Tumor–artery relationship | No radiographic evidence of arterial abutment (celiac, SMA, or hepatic artery) |

| Tumor–vein relationship | Tumor-induced narrowing <50% of SMV, PV, or SMV/PV |

| Borderline Resectable | |

| Artery | Tumor abutment (<180°) of SMA or celiac artery. Tumor abutment or short-segment encasement (>180°) of the hepatic artery |

| Vein | Tumor-induced narrowing of >50% of SMV, PV, or SMV/PV confluence. Short-segment occlusion of SMV, PV, SMV/PV with suitable PV (above), and SMV (below) to allow for safe vascular reconstruction |

| Extrapancreatic disease | CT scan findings suspicious, but not diagnostic, of metastatic disease (e.g., small indeterminate liver lesions which are too small to characterize) |

| Locally Advanced | |

| Artery | Tumor encasement (>180°) of SMA or celiac artery |

| Vein | Occlusion of SMV, PV, or SMV/PV without suitable vessels above and below the tumor to allow for reconstruction (no distal or proximal target for vascular reconstruction) |

| Extrapancreatic disease | No evidence of peritoneal, hepatic, extra-abdominal metastases |

| Metastatic | |

| Evidence of peritoneal or distant metastases | |

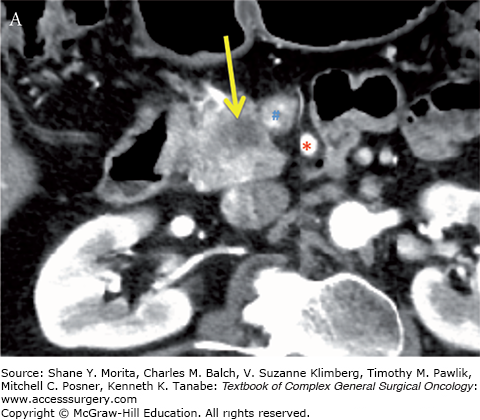

FIGURE 139-1

Resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma (low-attenuation mass) of the pancreatic head (yellow arrows). Note the tumor remains confined to the pancreas and is distant from the SMA (red asterisks) and does not abut or narrow the SMV (blue hashes). Axial CT images in the late arterial (A) and portal-venous (B) phases.

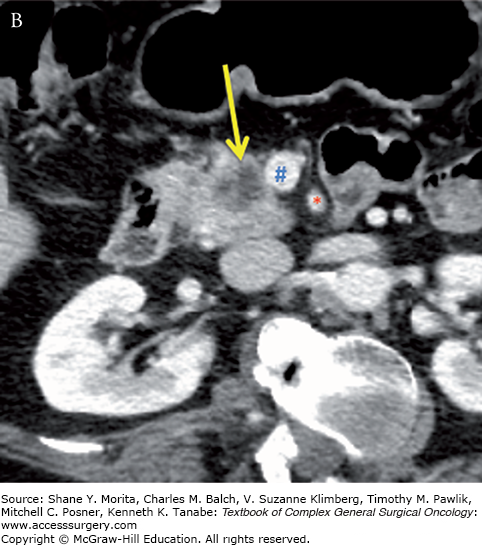

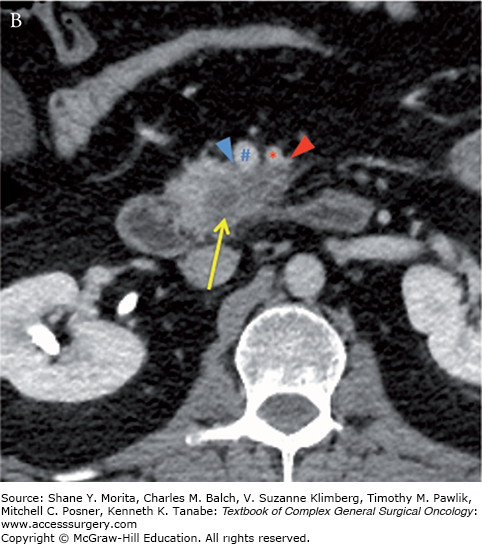

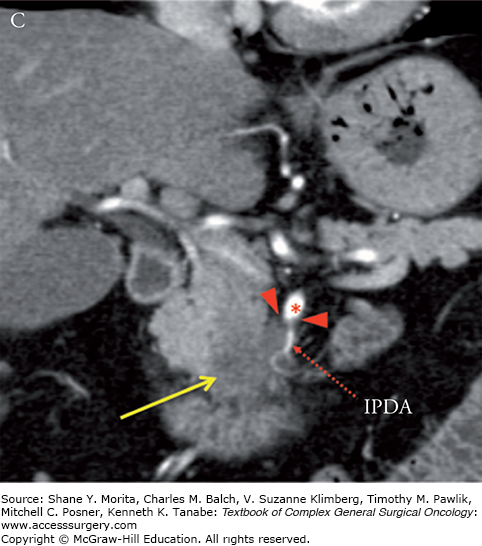

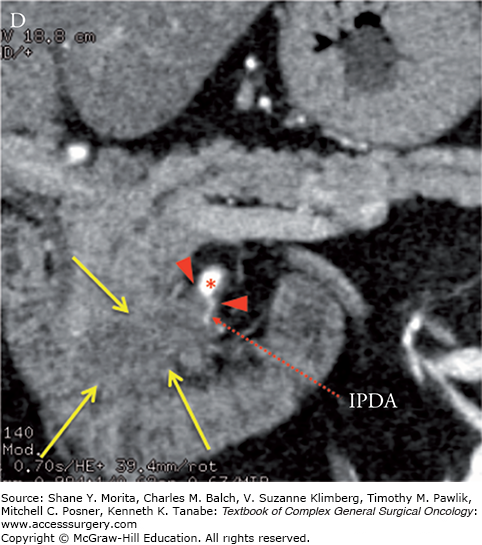

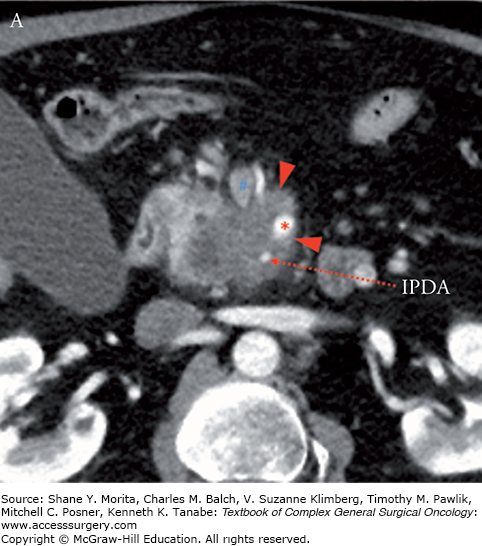

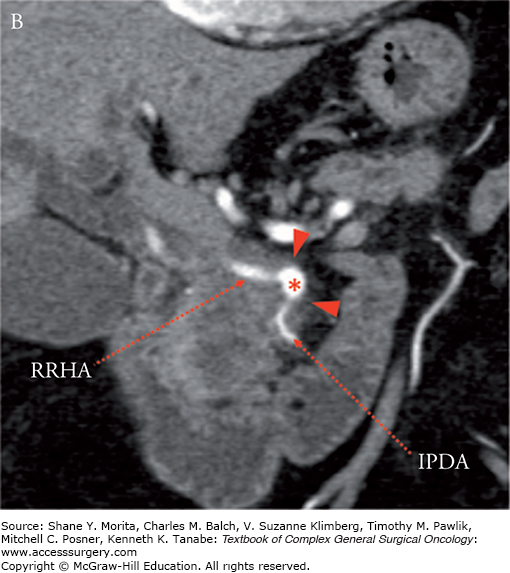

FIGURE 139-2

Borderline resectable adenocarcinoma (low attenuation mass) of the pancreatic head/uncinate process (yellow arrows) with tumor abutment (arrowheads) of the SMA (red asterisks) and SMV (blue hashes). Note the low-attenuation soft tissue that abuts the SMA (including IPDA branch) and SMV for 180 degrees or less and obliterates the expected normal fat plane. Axial late arterial (A), axial portal venous (B), coronal arterial (C), and curved planar venous (D) phase CT images. IPDA, inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery.

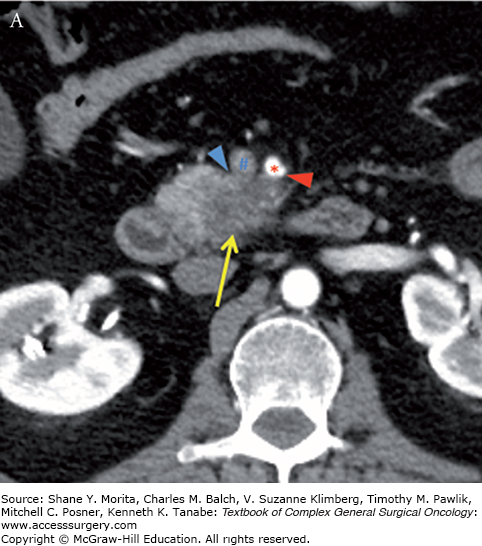

FIGURE 139-3

Locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma of the uncinate process with tumor encasement of the SMA (arrowheads). Note the low-attenuation soft-tissue which encases the SMA (red asterisks), inferior pancreaticoduodenalIPDA, and replaced right hepatic artery (RRHA) to SMA for greater than 180 degrees and greater than 50% “tear drop”-shaped narrowing of the SMV (blue hashes). Axial (A) and coronal (B) CT images in the late arterial phase. IPDA, inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery.

MCW vs. NCCN Definitions of Resectability

| MCW Definition | NCCN Definition | |

|---|---|---|

| Resectable | ||

| SMA, celiac artery | No abutment | No abutment |

| HA | No abutment | No abutment |

| SMV/PV | <50% narrowing of SMV, PV, SMV/PV | No abutment, distortion, tumor thrombus, or encasement |

| Borderline Resectable | ||

| SMA, celiac artery | <180° | <180° |

| HA | Short-segment encasementa |

|

| SMV/PV | >50% narrowing of SMV, PV, SMV/PVa |

|

| Other | CT scan findings suspicious but not diagnostic of metastatic disease | |

| Locally Advanced | Unresectable | |

| SMA, celiac artery | >180° | >180° |

| SMV/PV | Occlusion w/o option for reconstruction | Unreconstructable SMV/PV |

| Metastatic |

| |

| Extrapancreatic disease | Peritoneal or distant metastases | |

The accurate assessment of clinical stage is paramount, especially for borderline resectable disease, as more high volume centers gain experience with performing major vascular resections at the time of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD). Recent reports have demonstrated comparable survival among patients who undergo PD with or without vascular resection. In a single institutional series of 141 patients who underwent vascular resection, the survival among patients who underwent PD with vascular reconstruction was 23.4 months as compared to 26.5 months for those who underwent PD alone (p = 0.177).7 Several other institutions have reported similar survival data and in 2009, the Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association (AHPBA) and the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) developed consensus guidelines regarding the selection of patients for PD with vascular reconstruction.4,8–12 The authors concluded that PD with vein resection and reconstruction should be the standard of practice for pancreatic adenocarcinoma involving the SMV/PV confluence provided that (1) the venous reconstruction can be technically performed, (2) there is no involvement of the SMA or hepatic artery, and (3) an R0/R1 resection is expected. Therefore, the cornerstone to assessing the feasibility of surgical resection is the accurate characterization of the relationship of the primary tumor to the SMV/PV and the SMA/hepatic artery.

In addition to anatomic criteria for borderline resectability, additional risk factors have been identified by Katz et al which extend the classification using biochemical and clinical criteria (Table 139-3).13 Type A patients fulfill only the anatomic definition of borderline resectability based on tumor–artery abutment. Type B patients have either resectable or borderline resectable pancreatic cancer by anatomic criteria, but also have radiographic findings which are suspicious for, but not diagnostic of, metastatic disease. Type C patients have a marginal performance status or significant preexisting comorbidities which may preclude an immediate operation but for which an improvement is anticipated.

Borderline Resectable Pancreatic Cancer—MD Anderson Criteriaa,13

| A | |

| Anatomic criteria | Fulfills anatomic borderline criteria |

| B | |

| Anatomic criteria | Fulfills either resectable or borderline resectable criteria |

| Nodal involvement | Pathology or cytology positive for lymph node metastasis |

| Extrapancreatic disease | CT scan findings suspicious, but not diagnostic, of metastatic disease (e.g., small indeterminate liver lesions which are too small to characterize) |

| C | |

| Anatomic criteria | Fulfills either resectable or borderline resectable criteria |

| Performance status | ECOG 2 or significant comorbidities which preclude immediate surgical operation |

A thorough understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of various imaging modalities of the pancreas is essential to make well-informed management decisions. Overstaging of local tumor anatomy based on inaccurate or misinterpretation of imaging findings may preclude the possibility of a curative resection, whereas understaging may lead to unsuccessful intraoperative management. Herein, we describe the appropriate use of diagnostic imaging in the initial staging of pancreatic cancer.

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) is the primary method for diagnosing and staging pancreatic tumors of all histologies and remains the most important and useful imaging modality. MDCT provides the most comprehensive evaluation for clinical staging, especially with regard to delineating the extent of local tumor extension with specific reference to tumor-vessel anatomy. Because regional lymph node metastases are usually small in size, MDCT is less accurate at diagnosing lymph node metastases. To evaluate both the primary tumor anatomy and the presence of metastatic disease (liver, peritoneum, and lung), intravenous contrast-enhanced MDCT with dual-phase pancreatic protocol is required. Dual phase refers to image acquisition in the late arterial (pancreatic phase) and portal-venous phases. This allows for optimal enhancement of both the pancreatic/liver parenchyma and differential enhancement between tumor and normal parenchyma maximizing detection of tumors. Newer multidetector helical technology allows for submillimeter isotropic volumetric acquisition (higher resolution), faster image acquisition times, and the ability to perform multiplanar image reconstructions. Curved planar, multiplanar MIP (maximum intensity projection), and three-dimensional volume-rendered images can provide very high quality anatomic vascular detail and additional tumor–vasculature relationship detail. Clinical staging based on cross-sectional imaging involves determining the exact tumor vessel interface (SMA, celiac, hepatic arteries), as well as the presence or absence of tumor-induced narrowing/occlusion of the SMV or portal vein. Contrast-enhanced MDCT imaging has reported sensitivities as high as 84% (specificity of 98%) for detecting tumor encasement (>180° of circumferential vessel involvement), which is commonly associated with locally advanced, unresectable disease.14–16

The tumor–artery relationship is very accurately assessed on high-quality MDCT imaging in the absence of procedure-related inflammation. As such, the timing of the imaging should precede any planned invasive intervention, such as an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), to minimize the impact of procedure-related complications on accurate staging. Procedure-related complications can result in significant peripancreatic inflammation which can obscure the relationship of the primary tumor and adjacent vasculature, resulting in the inability to derive a clinical stage (resectable, borderline resectable or locally advanced), and result in under- or overstaging the true clinical stage.

Just as multiphasic and multiplanar imaging is vital for contrast-enhanced MDCT imaging of the pancreas, multiphasic, multisequence, and multiplanar MRI acquisition is required for staging of pancreatic cancer. Images are typically obtained as fat-suppressed T1-weighted images at various time points following the intravenous administration of gadolinium. A typical imaging protocol would include acquisition of T1-weighted fat-suppressed images at the following time intervals: prior to any contrast and at 20, 60, 120, and 180 seconds intervals. Although most tumors may be conspicuous on the immediate postcontrast images (late arterial or pancreatic phase), they can have highly variable appearance on later phase of imaging. Comparing MRI with MDCT, several studies suggest that MRI is comparable to the detection and the staging of pancreatic cancer.17,18 A meta-analysis of 68 studies performed by Bipat et al19 revealed the sensitivity of MRI to be 84% vs. 91% for MDCT. The sensitivity to detect surgical stage (resectable disease) was equivalent for both MRI and MDCT (82% and 81%, respectively). Sheridan et al20 compared dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and dual-phase helical MDCT in the preoperative assessment of suspected pancreatic cancer in a study of 33 patients. Two pairs of radiologists were blinded to the results of the other imaging modality and independently scored each study for the presence of tumor and resectability. The results were correlated with surgery. For determining tumor stage, the mean area under the receiver-operating characteristic curves were 0.96 and 0.81 (p = 0.01) and positive predictive value of 86.5% and 76% (p = 0.02) for MRI and CT, respectively. Staging of nodal metastases and peritoneal disease are well demonstrated in T2-weighted sequences with fat suppression and interstitial-phase gadolinium-enhanced fat-suppressed images in MRI. Studies have shown that dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI is equal or superior to contrast-enhanced CT for the detection of peritoneal metastases.21

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree