Gastritis is defined as histologically proven inflammation of the gastric mucosa. Worldwide, the primary cause of gastritis is

Helicobacter pylori infection. Approximately 50% of the world’s population is infected, the prevalence being higher in developing and disadvantaged countries, since the prevalence of

H. pylori is inversely related to socioeconomic status.

11The etiology of gastritis is established from clinical examination, serology (pepsinogens and antibodies against infectious agents and/or autoantigens), endoscopy (which should include biopsy), and histology. From a clinical standpoint, gastritis may be acute or chronic, though no clear cutoff in duration of disease has been established to distinguish them. In practice, the best way to separate them is by histological examination of gastric mucosal biopsies.

There are robust criteria for classifying gastritis by etiology, and strong correlations have been established between etiology and clinical course.

Table 20-2 lists the most common agents responsible for inflammatory conditions of the gastric mucosa and also indicates those most frequently associated with a prolonged (chronic) clinical course.

Gastritis: Basic Morphology

Histology identifies two main histological variants of the disease, that is, nonatrophic and atrophic gastritis.

12,13Nonatrophic gastritis is basically characterized by the presence of inflammatory cells within the lamina propria (lymphocytes, monocytes, polymorphs, and granulocytes), with no loss of the gland units normally present. However, inflammation may coexist with visible alterations, such as columnar epithelia hyperplasia, fibrosis of the lamina propria, and smooth muscle hyperplasia.

Atrophic gastritis is characterized by loss of appropriate glandular units.

12 The distinction between atrophic and nonatrophic gastritis is important because there is a well-established clinicobiological relationship between gastric atrophy and adenocarcinoma. The loss of appropriate

glands may coexist with the histological (inflammatory and/or hyperplastic) changes that also occur in nonatrophic gastritis.

The Inflammatory Infiltrate

The inflammatory infiltrate mainly consists of lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and granulocytes within the lamina propria and, less commonly, within the single glandular units. Lymphocytes may be either dispersed or packed in follicular lymphoid structures; lymphoid follicles are usually seen in

H. pylori infections. Visual analog scales (VASs) have been developed to improve interobserver consistency in scoring the mononuclear infiltrate.

14The term

lymphocytic gastritis is applied when a prominent lymphocyte infiltrate is detected within the glandular gastric epithelia. Different cutoff values have been suggested for assessing lymphocytic gastritis, ranging from about 20 to 25 inflammatory cells per 100 epithelial cells. Lymphocytic gastritis is suggestive of, but not diagnostic for, an immunomediated component in the inflammatory disease. An association has also been suggested between lymphocytic gastritis and celiac disease.

15, 16, 17 and 18 A more severe (nodular) lymphocytic intraglandular infiltrate that destroys or partially replaces the glandular structures (i.e., “lymphoepithelial lesion”) is almost pathognomonic of primary gastric B-cell lymphoma, which is almost always associated with

H. pylori infection.

Active inflammation of the gastric mucosa is defined as the presence of neutrophils within the lamina propria and/or in the glandular lumen. Activity is scored on a VAS according to the intensity of the neutrophilic infiltrate. Inflammatory activity suggests

H. pylori infection, the presence of which in cases of chronic inflammation should suggest the presence of an active infection; otherwise, the activity score is clinically of no prognostic value. Active inflammation also is seen in association with any mucosal erosion, as in NSAID-related gastritis, for instance (see below). Intramucosal eosinophilic infiltrate is prominent in eosinophilic gastritis, though the cutoff for its histological assessment (the number of eosinophils per high-power microscopic field) has not been firmly established. The etiopathogenesis and clinical significance of this histological category remain to be clarified.

17

Accessory Lesions

These include mucosal erosions, fibrosis of the lamina propria, smooth muscle hyperplasia, and columnar cell hyperplasia.

Mucosal erosions are commonly seen at endoscopy and histology; they can be due to infectious (H. pylori) or chemical (NSAIDs, drugs, bile) agents. Gastric epithelia adjacent to the erosion may undergo reactive hyperplastic changes (see below).

Expansion of the collagen tissue of the lamina propria (fibrosis), coupled with loss of glandular units, is defined as mucosal atrophy. Fibrosis of the lamina propria also may be focal, as seen in scars from prior peptic ulcers.

Hyperplasia of the muscularis mucosae may result from long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy; smooth muscle fascicle hyperplasia may push the glandular coils apart, expanding the interglandular spaces and giving rise to a pseudoatrophic pattern.

All inflammatory conditions of the gastric mucosa are associated with some degree of regenerative epithelial changes (regenerative hyperplasia), and this is generally seen associated topographically with erosions and peptic ulcers.

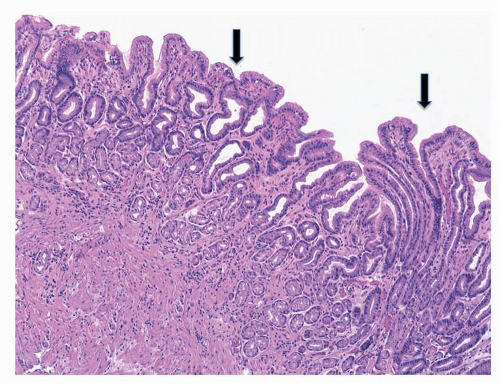

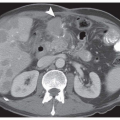

19 Chemicals (NSAIDs, bile reflux) or infectious stimuli increase the cell turnover by expanding the proliferative compartment of the glands (

neck region), resulting in hyperplastic

foveolae (

Fig. 20-1). Atypical regeneration of the glandular neck may be difficult to differentiate from dysplastic lesions (lesions “indefinite for noninvasive neoplasia”).

17,20Changes occurring in the oxyntic epithelia as a result of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) are sometimes considered hyperplastic changes, but they may simply represent a remodeling of the epithelial structure due to cytoskeletal rearrangements.

21