N. Cary Engleberg

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) refers to an illness that consists of profound, prolonged fatigue associated with other somatic or neuropsychological symptoms. The diagnosis is based on the patient’s subjective report of a compatible symptom cluster and the absence of any medical or psychiatric condition that might account for the complaints. Attempts to ascribe CFS to a single, coherent cause have been fruitless. The available evidence favors the notion that the syndromal definition identifies a heterogeneous population of patients in whom fatigue, pain, cognitive complaints, and viral-like symptoms, such as low-grade fever, sore throat, and tender lymph nodes, are the final common consequences of a variety of different causes. The current, prevailing etiologic hypothesis is that the disorder is a multifactorial condition in which genetic and environmental factors (including infection) interact to produce a disturbed capacity to manage and control stress, fatigue, and pain.

Other names for this disorder include myalgic encephalomyelitis (in Great Britain and Canada) and chronic fatigue and immune dysfunction syndrome (in the United States). Most authorities in the United States prefer the designation chronic fatigue syndrome because there is no convincing evidence that either inflammation of the central nervous system (CNS) or immune system dysfunction is directly responsible for the disorder. Postviral fatigue and postinfectious fatigue are less strictly defined designations for chronic idiopathic fatigue when the condition is perceived to be induced by an infectious disease and persists after resolution of the infection.

History

Although popular interest in CFS has been a relatively recent phenomenon, a historical perspective suggests that the illness is not new.1 For several centuries, an illness resembling CFS has been described repeatedly in the medical literature by different names. The illness has been attributed variously to neurologic, cardiovascular, endocrine, and infectious causes. The proximate association of infections, especially influenza, with chronic fatigue (i.e., neurasthenia) was appreciated in the late 19th century.2 In the 1950s, Spink3 found that nearly 20% of patients with serologic evidence of brucellosis developed lingering symptoms of fatigue, weakness, myalgic pain, mental confusion, and depression in the absence of evidence for continued, active infection, whether or not they had received treatment. He hypothesized that the development of “chronic brucellosis” involved an infection and a psychological predisposition. Later studies by Imboden and co-workers4 confirmed this impression by showing that patients with chronic brucellosis scored unfavorably on the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory relative to patients who had recovered from acute brucellosis. To test the hypothesis that a psychological propensity precedes the chronic fatigue illness, these authors conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of military personnel and dependents in Maryland after an outbreak of Asian influenza during the winter of 1957-1958.5 All subjects had completed the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory in August 1957, just before the epidemic. Prolonged convalescence from influenza was correlated with preexisting, unfavorable scores on certain subscales of this test. The typical Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory profile associated with prolonged postinfluenzal symptoms was nearly identical to that observed in patients with chronic brucellosis.

In 1985, two large series of patients with prolonged fatigue and other symptoms were reported to have elevated antibody titers against Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) compared with healthy controls.6,7 In the same year, a large outbreak of chronic fatigue with associated symptoms and serologic tests suggesting chronic EBV infection occurred in the area of Lake Tahoe, Nevada.8 It was proposed that idiopathic chronic fatigue might be due to “chronic mononucleosis.” This hypothesis was appealing because it had long been observed that persistent fatigue may follow documented acute mononucleosis in a small proportion of cases.9–12 However, several subsequent investigations failed to confirm a role for active EBV replication in the persistence of this clinical syndrome.13,14,15,16,17 During the past 4 decades, numerous other infectious agents have been proposed as the cause of CFS, including Candida albicans, Borrelia burgdorferi, enteroviruses, cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus 6, spumavirus, Bornavirus, and retroviruses, with the most recent controversy over a xenotropic murine retrovirus, XMRV (Table 133-1). The evidence that active infection with any of these agents causes a significant proportion of chronic fatigue cases is either inconclusive or refuted by subsequent investigations.

TABLE 133-1

Proposed Infectious Causes of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

| PROPOSED ETIOLOGIC AGENT | REFERENCES | |

| Suggestive Studies | Negative Studies | |

| Epstein-Barr virus | 6, 7, 173 | 13, 14, 15, 16, 174–176 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 177, 178 | 13, 14, 174–176 |

| Human herpesvirus 6 | 45, 46, 179, 180 | 13, 14, 175, 176, 181, 182 |

| Human herpesvirus 7 | 183 | 46, 175, 179, 182 |

| Human herpesvirus 8 | — | 46, 175, 184 |

| Enteroviruses | 185–187 | 13, 14, 188–191 |

| Parvovirus | 39, 192 | 175, 193, 194 |

| GB virus-C | 195 | |

| Human spumavirus | 196 | — |

| Bornavirus | 197, 198 | 199 |

| Human retrovirus | 200 | 201–203 |

| Xenotropic murine retrovirus (XMRV) | 49, 50 | 54, 56–58 59 (retraction of 49) 60 (retraction of 50) |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | 204 | 205, 206 |

| Brucella spp. | 207 | 3 |

| Mycoplasma spp. | 208, 209 | 210 |

| Candida albicans | 211, 212 | 213 |

To stimulate productive research on this clinical problem, the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) sponsored a series of research conferences between 1985 and 1994. One goal of these conferences was to prepare a workable consensus definition of CFS that could be applied uniformly by investigators studying the epidemiology, clinical features, etiology, and treatment of the disorder (Table 133-2).

Epidemiology

Fatigue is one of the most common complaints encountered in general medical practice. In most patients, the complaint is eventually attributed to a diagnosable medical condition or is short-lived. According to the most recent consensus conference definition, severe fatigue that remains unexplained after baseline physical and laboratory examinations and persists for more than 6 months is designated as idiopathic chronic fatigue. Patients with idiopathic chronic fatigue who also complain of four or more of the associated symptoms listed in Table 133-2 may be considered to have CFS.18

Because the case definition requires a medical evaluation, it can be applied only to study the prevalence of CFS in populations who seek medical attention. In a general medical practice in Boston, idiopathic chronic fatigue was reported by 8.5% of patients, but only 0.3% could be diagnosed with CFS.19 The CDC ascertained the national prevalence of CFS by conducting case findings through a network of physicians in four cities. The prevalence, age, and sex distribution were remarkably similar in the four cities. The prevalence ranged from 3 to 11 per 100,000 population. Patients were predominantly women (7 : 1) and clustered in the 30- to 50-year age group.20 Similar estimates of prevalence were reported from studies in Australia and the United Kingdom.21,22 The characteristic predominance of upper middle class white women in their 30s and 40s resulted in the pejorative term “yuppie flu.” These and other observations are biased, however, by reliance on clinic-based case ascertainment. When a random telephone survey was conducted in the San Francisco area, a different epidemiologic pattern emerged.23 The overall prevalence of subjects reporting a CFS-like illness was 0.2% of the population, and the female predominance was less dramatic (2.9 : 1). The age distribution was the same as that seen in clinic-based studies, but the distribution of cases by income showed higher rates in persons with family incomes less than $40,000, suggesting that the perception of “yuppie flu” is an artifact of health care use by the affected populations. The rates of CFS-like illness were higher in African Americans and Hispanics than in whites and Asian Americans, and there was no preponderance of cases in any individual occupational group. Similar findings have been reported in other community-based studies.24–27 These studies suggest that there is a high frequency of chronic fatigue in all communities; however, review of individual medical records reveals a medical or psychiatric condition to account for a majority of the cases. In addition, the prevalence of idiopathic chronic fatigue (usually about 1% to 6%) is much greater than the number that meets the CDC consensus criteria for CFS (0.1 to 0.3%).

Outbreaks of idiopathic illness consistent with CFS have been reported occasionally since the 1940s.28 In many of these outbreaks, the involvement of an infectious agent is unlikely because certain subgroups of the population at risk were affected disproportionately. Large hospital outbreaks in Los Angeles and London affected the professional staff but not the hospitalized patients or nonprofessional staff.29,30 An acute outbreak of neuromyasthenia in New Zealand resulted in CFS in many of the affected individuals. A 10-year follow-up of these cases indicated that most patients had recovered partially or completely.31

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Attempts to elucidate the pathophysiology of CFS have been hampered by several methodologic problems. Foremost among these is the problem of selecting a homogeneous group of subjects for study from among patients identified by the working definition. In a symptom cluster analysis of patients meeting the CDC criteria, at least two distinct subgroups emerged—one having numerous syndromal and nonsyndromal symptoms with high severity scores and a second, larger group with limited symptoms and only moderate severity.32 A recent genetic and clinical symptom analysis suggests the existence of seven discrete subgroups.33

It has long been appreciated that some patients have an acute onset associated with an infectious disease or other definable stressor, whereas others describe an insidious and progressive onset. Most patients have past or current psychiatric disorders,34–36 whereas some have no past or present psychiatric symptoms. There is no reason to assume a priori that patients with these diverse clinical circumstances have the same disorders simply because they meet the CDC criteria at the time of presentation.

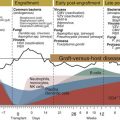

Role of Infection

Infectious causes of CFS have been proposed (see Table 133-1), but there is no reproducible evidence that any single agent is responsible for any significant proportion of these illnesses. Postinfectious fatigue cases indistinguishable from CFS may immediately follow a diagnosed infection (e.g., EBV infection, influenza, brucellosis, giardiasis), including some that are highly localized geographically (e.g., Lyme disease, Q fever, Ross River virus infection).5,37–41 In a prospective study, Hickie and co-workers12 reported that postinfectious fatigue occurs at a rate of approximately 12% whether the instigating infection is EBV, Q fever, or Ross River virus. Most of these patients met criteria for CFS as well. Others have reported that postinfectious and idiopathic cases have indistinguishable clinical and psychosocial features.42 Prolonged convalescence from infectious mononucleosis is a well-recognized phenomenon.9–11 A more recent prospective study of adolescents with infectious mononucleosis showed that at 6 and 24 weeks of follow-up, 13% and 4%, respectively, had prolonged fatigue that met CDC criteria.43 The use of steroids during the acute phase of mononucleosis was not associated with prolonged postinfectious fatigue in this study.

The occurrence of clinically indistinguishable “postinfectious” fatigue states after several unrelated infections supports the concept that CFS is a nonspecific sequela to a variety of illnesses rather than a disease with a single, specific infectious cause. Controversy persists about whether chronic fatigue can be triggered by any infectious or traumatic event or whether only a particular type of infection or trauma is necessary. However, patients seen in general practice for common infections do not have an increased frequency of prolonged fatigue relative to patients seen for other medical problems.44

Although there was never any direct virologic evidence favoring chronic, persistent EBV infection as a cause of CFS, a significant body of negative research has accumulated to reject this hypothesis. These studies showed no significant differences in serologic titers,13,14 shedding of virus in saliva,17 blood lymphocyte–transforming activity,16,17 or EBV-specific cytotoxic lymphocytes16 between patients and healthy controls. In addition, a large treatment study compared intravenous and oral acyclovir with placebo in CFS patients and failed to show any benefit.15 Similarly, negative microbiologic data have been collected for other specific infectious agents (see Table 133-1). The possibility that CFS patients may reactivate latent viruses more frequently than healthy individuals has been proposed,45,46 but it is not clear how or whether viral reactivation affects the ongoing symptom complex.47 For example, Chia and Chia48 have recently observed that enterovirus RNA and VP1 are found four times more frequently in the stomachs of CFS patients than in healthy controls. However, like many similar virologic observations, it is not clear whether persistent enterovirus is a cause or a consequence of the syndrome.

The latest controversy concerning CFS etiology occurred after a 2009 publication implicating xenotropic murine retrovirus (XMRV) in 67% of 101 patients but only 3.7% of 218 healthy controls.49 A separate research group reported a similar disparity in the frequency of murine leukemia virus (MLV)–related sequences among CFS patients and healthy blood donors.50 Initially, criticism of these reports from established researchers focused on poorly described selection of cases and controls, potential sources of bias, and uncertainty about the generalizability of the findings.51–53 However, the most serious challenge came from DNA sequence analysis showing that viruses in an established murine cell line are ancestral to viruses detected in the human samples, suggesting that the human samples were contaminated with mouse DNA.54 Several subsequent studies failed to show any association of XMRV with CFS,55,56,57,58 and the two studies that initially found an association were eventually retracted (see Table 133-1).59,60

Role of the Autonomic Nervous System

In 1995, researchers at Johns Hopkins University reported that chronic fatigue patients had abnormal responses to a 45-minute tilt-table test protocol.61 Virtually all of the patients had syncope or reproduction of fatigue symptoms, whereas only about one third of healthy controls had an abnormal response. These investigators proposed that the persistent fatigue may be attributable to neurally mediated hypotension. Subsequent studies have provided mounting evidence that younger patients with CFS have increased sympathetic activity at rest with exaggerated cardiovascular response to orthostatic stress. Resting catecholamine levels are increased, and thermoregulatory responses suggest increased sympathetic activation at rest.62,63 This may be manifest as positional orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) without hypotension.64 However, Katz and co-workers65 failed to find any difference in the frequency of orthostatic intolerance among adolescents 6 months after infectious mononucleosis whether they met criteria for CFS or had completely recovered.

Attempts to treat CFS as neurally mediated hypotension have not been successful. The investigators who demonstrated abnormal tilt-table testing in young patients with CFS used combinations of fludrocortisone, atenolol, and sertraline with increased salt intake to treat a cohort of patients. Initially, they reported a favorable durable response in 39% of patients.61 However, two subsequent controlled trials failed to show any benefit using this approach to therapy.66,67

Role of the Immune System

Some of the proposed inciting and perpetuating factors involve disruptions in various biologic systems (e.g., the immune system, skeletal muscle, heart, CNS). Although subtle alterations in some of these systems have been identified in patients, similar changes are observed in individuals without symptoms. Differences in various measures of immune function (e.g., cytokine levels, in vitro lymphocyte function, flow cytometry) have been observed by comparing CFS patients and healthy persons; however, many of the studies are inconsistent with one another or have not been reproduced. One prospective study of postinfectious fatigue failed to find any significant differences in the levels of eight cytokines comparing patients and controls.68

The most consistent immune alterations have included an increase in T lymphocytes expressing activation markers69 (e.g., in the number of lymphocytes bearing the CD45RA differentiation marker70). These findings suggest mild activation of the cellular immune system, but the relevance of these alterations is unclear, given the inconsistent immunologic differences among monozygotic twin pairs that are discordant for CFS.71 It is also not clear that a change in lymphocyte subsets occurs in conjunction with clinical improvement.72

Another immunologic finding more common in CFS patients than in healthy controls is a reduction in natural killer cell function and in the number of lymphocytes bearing the CD16 marker.73,74 This finding raised the concern that malignancies might occur at an increased rate in CFS. Analysis of cancer registries following the large 1985 Lake Tahoe outbreak did not support this notion.75 Subsequently, Chang and co-workers76 queried the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)-Medicare registry that includes 1.2 million cancer cases and compared them with 100,000 controls. The frequency of a CFS diagnosis more than 1 year before selection was 0.5% in both the cancer and control groups; however, an extensive subgroup analysis showed a small increase in the odds of CFS in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A study of all-cause mortality shows no increased rates for CFS patients.77

Abnormalities of B lymphocytes have been present less consistently among CFS patients. However, a Norwegian research group reported a transient beneficial effect of rituximab therapy in a majority of 15 treated CFS patients compared with 15 placebo-treated controls.78 This unique study requires confirmation before any firm conclusions can be made concerning the role of B lymphocytes in CFS pathogenesis.

Dysregulation of RNase L has been studied as a common feature of CFS. Normally, the presence of double-stranded RNA (i.e., from viruses) activates expression of the enzyme 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase. The 2′,5′-adenylate oligonucleotides generated from this activity bind to and activate RNase L, which degrades viral and some host RNAs. CFS patients are purported to have increased levels of 2′,5′-adenylate oligonucleotides and RNase L activity.79,80 In addition, a low-molecular-weight RNase L molecule has been detected more frequently in CFS patients than in healthy controls (88% vs. 32%81,82). Activation of this pathway in CFS could be regarded as evidence of a response to viral infection or, alternatively, as evidence of disturbed immune regulation that results in unnecessary degradation of host RNA.

A synthetic double-stranded (ds)RNA rintatolimod (Ampligen), activates 2′,5′-oligoadenylate synthetase via Toll-like receptor 3 and generates RNase L. This drug, given intravenously, has been reported to benefit CFS patients in two randomized, placebo-controlled trials.83,84 However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has repeatedly rejected a new drug application for Ampligen based on concerns about study design and efficacy. In any case, the failure of the drug to make CFS worse argues against exaggerated RNase L levels and RNA degradation as a cause of fatigue.

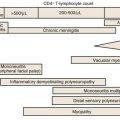

Role of the Central Nervous System

Because idiopathic chronic fatigue usually includes neuropsychological symptoms and subtle alterations of hormones regulated at the hypothalamic level, the hypothesis that the CNS is the principal site of the pathophysiology has gained support in recent years. Accumulating data from CNS imaging studies support this notion, but the significance of these findings still is unclear.45,85–88 Investigators have observed regions of reduced cerebral blood flow in CFS patients relative to healthy controls88,89; however, these findings were not confirmed in a study of single-photon emission computed tomography scanning in monozygotic twins discordant for CFS.90

Urinary free cortisol levels have been shown to be lower in patients with CFS than in age-matched and sex-matched healthy controls, although the means of both groups are within the defined normal range.91,92 Exaggerated adrenal responsiveness to corticotropin infusions in these patients suggests that a subtle defect in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis activity exists.93 The disturbance also results in a flattening of the diurnal pattern of cortisol secretion and enhanced sensitivity of the axis to negative feedback.94,95 Nater and co-workers96 reported an attenuation of morning salivary cortisol in medication-free CFS patients compared with well-matched controls but noted that the effect was limited to women. Reduced HPA-axis activity and hyperresponsiveness have also been observed in fibromyalgia and in post-traumatic stress disorder, whereas enhanced activity of the axis is typical of major depressive disorder.97 In contrast, gonadotropin levels are not affected by either CFS or fibromyalgia.98 These findings suggest the presence of a common pathophysiology in CFS and other stress-related disorders that is centered in the CNS.

The finding of depressed HPA-axis activity as a feature of chronic fatigue illnesses motivated a study at the National Institutes of Health in which patients received either replacement hydrocortisone or placebo for 3 months. This study and a subsequent trial suggest that there was minor improvement in the hydrocortisone group during treatment.99,100 There was also profound and sustained suppression of the HPA axis and loss of bone density, which prompted investigators to recommend against the use of steroids for treatment.100,101 Another attempt to boost the HPA axis pharmacologically was made in a randomized, controlled trial of the drug galantamine (a central stimulant of HPA-axis activity). The study showed no substantial benefit.102 Therefore, although HPA-axis disturbances may be present in CFS, attempts to correct these disturbances do not relieve symptoms. This suggests that any fundamental disturbance occurs at a more complex level in the brain.

As in the earlier studies of brucellosis and influenza by Imboden and co-workers,5 contemporary investigators have found that when patients present with a “viral illnesses” in general practice, psychiatric morbidity, belief in vulnerability to viruses, and attributional style at initial presentation are more important predictors of fatigue 6 months later than are “viral” symptoms during the initial infection.103 Several studies have reported that a prior history of depression is frequently present in chronic fatigue states and may represent an important predisposing condition.103–106 Perhaps the most convincing observations come from the National Child Development Study in the United Kingdom, a study that prospectively collected health and psychosocial data on huge cohorts of individuals from birth to adulthood. Cohorts born in 1946, 1958, and 1970 were analyzed in separate studies that came to similar conclusions. In the 1946 cohort, 3035 participants were assessed for CFS by self-report and a structured interview at age 53. The study found that those with psychopathology assessed by standard interview instruments at ages 15 and 36 were 2.65 times more likely to report CFS later in life. Moreover, the likelihood of CFS was greatest in those with the most severe psychiatric disorders.107 This study was confirmed using the 1958 cohort of 11,419 participants.108 Those with psychopathology when assessed at age 33 were 2.8 times more likely to report CFS at age 42. In addition, this analysis showed that psychopathology and sedentary behavior during childhood and extremes of physical activity in adulthood are not associated with CFS later in life.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree