Abstract

Disorders of histiocytic and dendritic cell origin, traditionally referred to as histiocytoses [1], form a group of extremely rare tumours, characterized by variable malignant potential and unpredictable clinical course, from spontaneously regressing to rapidly progressing. While the neoplastic character of some of these entities is still debated, the most commonly acknowledged predictors of malignant behaviour remain as morphological features, i.e. degree of cellular anaplasia. Some of these disorders show predilection for skeletal involvement (Langerhans cell histiocytosis, LCH; Erdheim–Chester disease, ECD) but bone marrow (BM) infiltration is infrequent. In turn, entities classified as frankly malignant (e.g. histiocytic sarcoma, HS) most often form tumoural masses in lymph nodes or at extranodal sites. Interestingly, many of the tumoural lesions in this category demonstrate ability to transdifferentiate to and from other malignancies, including lymphomas and leukaemias. Therefore although primary histiocytic or dendritic cell disorders are most commonly diagnosed in skeletal, soft tissue or lymph node biopsies, BM biopsies (BMB) and aspirates may be obtained for staging purposes or in cases when occurrence of secondary malignancy is suspected.

Introduction

Disorders of histiocytic and dendritic cell origin, traditionally referred to as histiocytoses [1], form a group of extremely rare tumours, characterized by variable malignant potential and unpredictable clinical course, from spontaneously regressing to rapidly progressing. While the neoplastic character of some of these entities is still debated, the most commonly acknowledged predictors of malignant behaviour remain as morphological features, i.e. degree of cellular anaplasia. Some of these disorders show predilection for skeletal involvement (Langerhans cell histiocytosis, LCH; Erdheim–Chester disease, ECD) but bone marrow (BM) infiltration is infrequent. In turn, entities classified as frankly malignant (e.g. histiocytic sarcoma, HS) most often form tumoural masses in lymph nodes or at extranodal sites. Interestingly, many of the tumoural lesions in this category demonstrate ability to transdifferentiate to and from other malignancies, including lymphomas and leukaemias. Therefore although primary histiocytic or dendritic cell disorders are most commonly diagnosed in skeletal, soft tissue or lymph node biopsies, BM biopsies (BMB) and aspirates may be obtained for staging purposes or in cases when occurrence of secondary malignancy is suspected.

Cell of Origin Classification

The currently accepted definition of the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) was first proposed in 1969 [2] but is constantly evolving [3]. The MPS is responsible for innate immune responses and consists of monocytes circulating in peripheral blood, macrophages or tissue-residing histiocytes and dendritic cells (DCs). Monocytes and macrophages originate from haematopoietic precursors in BM, participate in both acute and chronic phase of inflammation [4], and can differentiate into other MPS cell types. Dendritic cells remain the subjects of intensive studies but their development seems not to be fully understood yet. They may originate from embryonic precursors (dermal and mucosal Langerhans cells, LCs) or from common DC precursor (CDP) found in BM, developing through circulating precursors (pre-DC) [5]. From marrow CDPs originate both plasmacytoid DCs and other DC subsets found in lymphatic tissue and other organs, including the so-called mesenchymal- or stromal-derived DCs.

The MPS cells are dynamic and may demonstrate overlapping morphological or phenotypical features. In the tumoural context, disorders of BM precursor origin include LCH, Langerhans cell sarcoma (LCS), ECD, HS and interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma (IDCS). Tumours of mesenchymal- or stromal-derived DC origin include follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (FDCS), indeterminate dendritic cell sarcoma (INDCS), disseminated juvenile xanthogranuloma (DXG, systemic counterpart of juvenile xanthogranuloma, JXG), and fibroblastic reticular cell tumour (FRCT). From the morphological perspective, histiocytic infiltrates are prominent in ECD, DXG and HS, whereas transformed oval or spindle-shaped DCs dominate the picture in the remaining entities.

In the recent classification by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1], all the above-mentioned disorders are grouped under the category of ‘Histiocytic and Dendritic Cell Neoplasms’ (Table 7.1). However, the Histiocyte Society proposed a revised classification involving both morphological, phenotypical and molecular features as well as clinical presentation and radiological findings (Table 7.2) [6]. Several of these entities were discussed in Chapter 6 (ECD, Rosai–Dorfman disease (RDD) and haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)) and the remainder will be addressed below and summarized in Table 7.3.

Table 7.1 Classifications of histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms according to WHO 2017 [1].

| Neoplasm | Malignant potential | |

|---|---|---|

| Histiocyte derived | Erdheim–Chester disease (ECD) | Variable, mostly chronic disease |

| Xanthogranuloma family (juvenile XG, disseminated XG, adult XG) | Benign, systemic variant more aggressive | |

| Histiocytic sarcoma (HS) | Malignant, poor prognosis | |

| Dendritic cell derived | Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) | Variable |

| Langerhans cell sarcoma (LCS) | Malignant, poor prognosis | |

| Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma (IDCS) | Malignant, poor prognosis | |

| Indeterminate dendritic cell sarcoma (INDCS) | Malignant, variable course | |

| Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma (FDCS) | Malignant, good prognosis |

Table 7.2 Classification of histiocytoses according to Histiocyte Society 2016 [6].

| Tumour group | Clinical features | Most common entities |

|---|---|---|

| L Group | Variable clinical presentation Skeletal involvement common Endocrinological and/neurodegenerative complications possible | Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

| Erdheim–Chester disease | ||

| Disseminated juvenile xanthogranuloma | ||

| C Group | Mucosal and/or dermal lesions | Xanthogranuloma family |

| Benign cephalic histiocytosis | ||

| Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis, cutaneous RDD | ||

| R Group | Classical presentation with lymphadenopathy and systemic symptoms Extranodal involvement in 43% cases Association with ALPS and Autoimmune Lymphoproliferative Syndrome IgG4 disease | Rosai–Dorfman disease family |

| M Group | Frankly malignant Nodal or extranodal masses Association with other haematological malignancies | Histiocytic sarcoma Interdigitating dendritic cell sarcoma Indeterminate dendritic cell sarcoma Langerhans cell sarcoma (Follicular dendritic cell sarcoma excluded) |

| H Group | Systemic hyperinflammatory syndrome Primary FHL and Familial Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis, due to inherited mutations Secondary, most commonly due to infection, autoimmunity, malignancy | Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis Macrophage activation syndromes |

Table 7.3 Clinical and pathological characteristics of main histiocytic and dendritic cell disorders.

The field of histiocytic and dendritic cell disorders is undergoing constant evolution and attracts a lot of scientific attention. It should be noted, though, that of all haematopoietic diseases of neoplastic character, histiocytoses are the rarest and the most elusive. The crude incidence rate of malignant histiocytic and DC tumours in European countries was 0.053 × 100,000/year in 2007, with estimated 278 new cases in 2013 [7].

Phenotypic Features

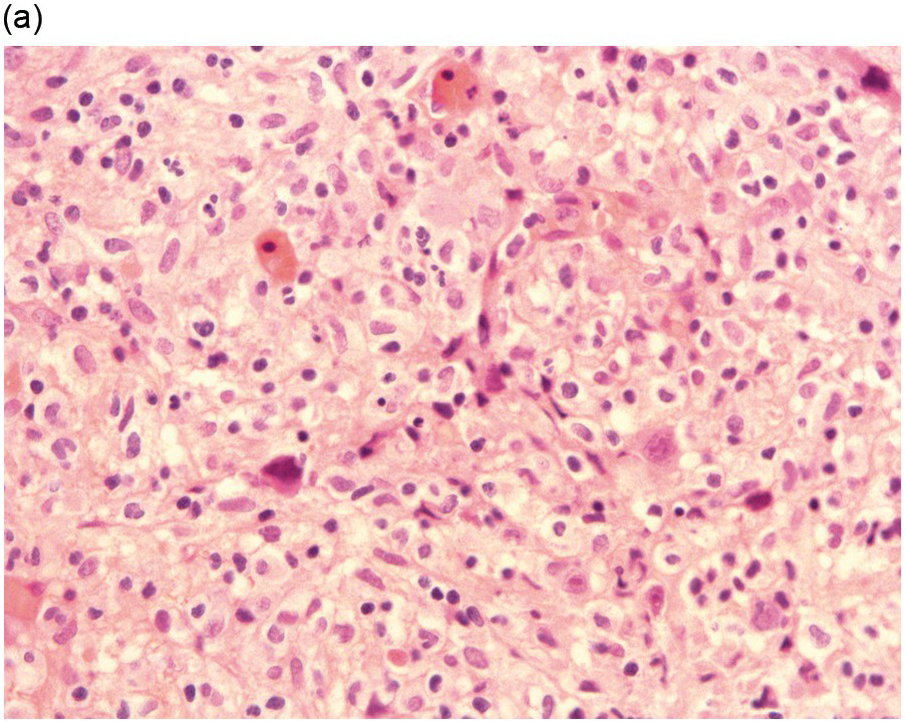

It is generally recognized that monocytic/histiocytic tumours are composed of cytoplasm-rich ovoid cells, whereas DC lesions have a more stellate cell appearance. In both groups spindle cells may be a prominent feature and a variable amount of a non-neoplastic inflammatory component, including plasma cells, small lymphocytes, eosinophils and reactive histiocytes, may be found. The tumour cell component itself may be low, e.g. in LCH it may account for only 8% of the entire infiltrate [8].

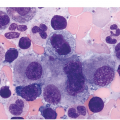

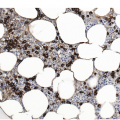

Histiocytic tumours may show prominent vacuolization, at times resembling foamy macrophages or storage cells (Figure 7.1). Lipid accumulation may also be a prominent feature, such as in JXG or ECD. Giant or multinucleated forms, including Touton cells, may be numerous, and fibrosis is usually seen in ECD. Infiltrates in tissue samples may remind one of mast cell aggregates.