Abstract

Diagnosing anemia in a neonate is only a first step in a process that includes: clarifying the pathology responsible for the anemia, instituting the best-known therapy (if indeed a treatment is warranted), and then evaluating whether the therapy administered was effective in alleviating the anemia. Chapters 4, 6–10 and 20 focus on the principal varieties of anemia that occur in the neonatal period. The purpose of this chapter is not to repeat material detailed there, but to provide a method for navigating the somewhat unique process of diagnosing neonatal anemia and then discovering its cause. To accomplish this purpose, the chapter is organized into two parts: (1) making the diagnosis of anemia in neonates using reference intervals appropriate for gestational and postnatal age, and (2) following an evaluative algorithm to identify the underlying cause of the anemia in a neonatal patient.

Diagnosing anemia in a neonate is only a first step in a process that includes: clarifying the pathology responsible for the anemia, instituting the best-known therapy (if indeed a treatment is warranted), and then evaluating whether the therapy administered was effective in alleviating the anemia. Chapters 4, 6–10, and 20 focus on the principal varieties of anemia that occur in the neonatal period. The purpose of this chapter is not to repeat material detailed there, but to provide a method for navigating the somewhat unique process of diagnosing neonatal anemia and then discovering its cause. To accomplish this purpose, the chapter is organized into two parts: (1) making the diagnosis of anemia in neonates using reference intervals appropriate for gestational and postnatal age, and (2) following an evaluative algorithm to identify the underlying cause of the anemia in a neonatal patient.

Making the Diagnosis of Anemia

Simply stated, anemia is a pathological decrease, below normal, in the quantity of red blood cells [1]. In neonatal hematology, anemia is typically defined by a hemoglobin concentration, or a hematocrit, below the 5th percentile of the appropriate reference interval [2]. Comparison with an “appropriate reference interval” is essential for diagnosing anemia in neonates. This is because the hemoglobin and hematocrit normally increase steadily in a fetus during gestation, and then decrease in a characteristic pattern for several weeks after birth [2]. These physiological perinatal changes in what the hemoglobin and hematocrit “should be” necessitate that to properly label a neonate as “anemic,” the patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit must be compared with appropriate normative figures or tables, such as those provided in Chapter 24.

For adult patients, the diagnosis of anemia involves comparing the patient’s hemoglobin/hematocrit with normative values of healthy volunteers of the same sex. This is because mature males tend to have somewhat higher hemoglobin/hematocrit values than do mature females [3]. However, this female–male difference is not observed in neonates at birth or during the neonatal period [4]. Therefore, separate sex-specific figures/tables are not needed to diagnose anemia in neonates. Moreover, for adult patients, the diagnosis of anemia requires comparing the patient’s hemoglobin/hematocrit with values obtained at a grossly similar altitude above sea level. This is because patients living at high altitude develop somewhat higher hemoglobin/hematocrit values than do those living at sea level [5]. This altitude difference does not appear to apply to neonates at birth, at least not at altitudes up to 5,000 ft (1,524 m) or so above sea level [4]. It is not clear whether neonates born at extremely high altitudes (such as La Rinconada, Peru at 16,830 ft [5,130 m]) have significantly higher hemoglobin/hematocrit values at birth than those in the reference intervals of Chapter 24. Thus, it is not known whether new reference interval figures/tables are needed to assist in diagnosing anemia of babies born in very high altitude settlements such as certain communities in Peru, China, Nepal, Argentina, and Bolivia.

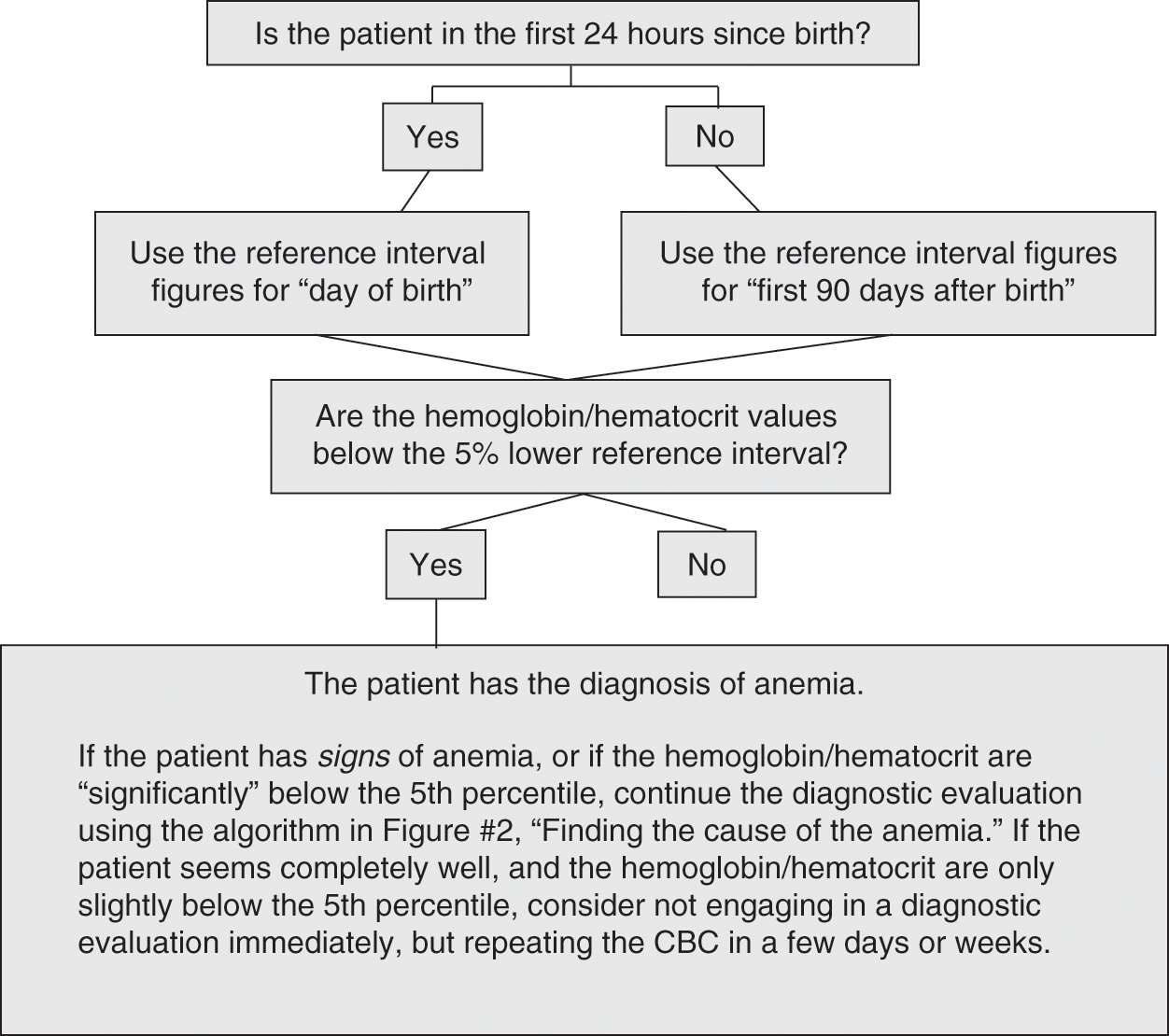

Not every neonate with anemia (as defined by a hemoglobin/hematocrit below the 5th percentile of the appropriate reference interval) requires a diagnostic evaluation to determine the cause of the anemia. If they did, 5% of all neonates would need to undergo such an evaluation. With four million births annually in the USA, this would mean 200,000 neonates/year would be classified as anemic, and in need of a diagnostic evaluation. Rather, some neonates will have a hemoglobin/hematocrit only slightly below the 5th percentile cutoff limit. If such a neonate is well appearing, with normal vital signs, and with a normal physical examination, one can forego a detailed diagnostic evaluation to seek the cause of the anemia; perhaps simply repeating the hemoglobin/hematocrit after a few days or weeks. Contrariwise, neonates with hematocrit/hemoglobin levels far below the 5th percentile level, or with signs of anemia, such as pallor, tachycardia, and or tachypnea, should undergo a diagnostic evaluation to identify the underlying cause of the anemia and to assist in selecting the best treatment and follow-up plans.

An algorithm that can be followed to confirm a diagnosis of anemia in a neonate is shown as Fig. 7.1. It involves applying the proper reference intervals (found in Chapter 24), and considering whether the anemia might be too mild, trivial, or asymptomatic to warrant commencing a larger and more definitive evaluation of causation.

The algorithm in Fig. 7.1 begins by applying the appropriate reference intervals for hemoglobin and hematocrit. These ranges gradually increase during the period in utero. In applying these reference intervals, it should be remembered that in newborn infants the anatomic site of the blood drawn to measure the hemoglobin and hematocrit influences the test result [6]. Perfusion of small vessels in the extremities can be relatively poor, particularly in the hours immediately after birth or during hypotension or skin cooling, and this can result in increased transudation of fluid and capillary hemoconcentration. Consequently, the hemoglobin and hematocrit of capillary blood can be 5% to 10% higher than from venous blood [7]. The difference between capillary and venous values is greatest on the day of birth and typically disappears by about 3 months of age. The discrepancy is greatest in preterm infants and in those with hypotension, hypovolemia, and acidosis. Differences can be minimized, but not fully resolved, by warming the extremity before sampling, obtaining freely flowing blood, and discarding the first few drops [7]. The interpretation of serial observations necessitates the consistent use of one anatomic site of blood sampling (i.e., all vascular or all capillary).

Hemoglobin concentrations should increase during the first hours after birth, attributable in part to a shift of fluid from the intravascular compartment, but also to the transfusion of fetal red cells from the placenta at the time of birth [6, 7]. After the first day, the reference intervals for hemoglobin and hematocrit gradually decrease, as shown in Fig. 24.2 (term and late preterm neonate) and Fig. 24.3 (preterm neonates). Once anemia has been diagnosed in a neonate, and it has been decided that this is not a minimal or trivial condition, attention should next be turned to discovering its cause.

Finding the Underlying Cause of the Anemia

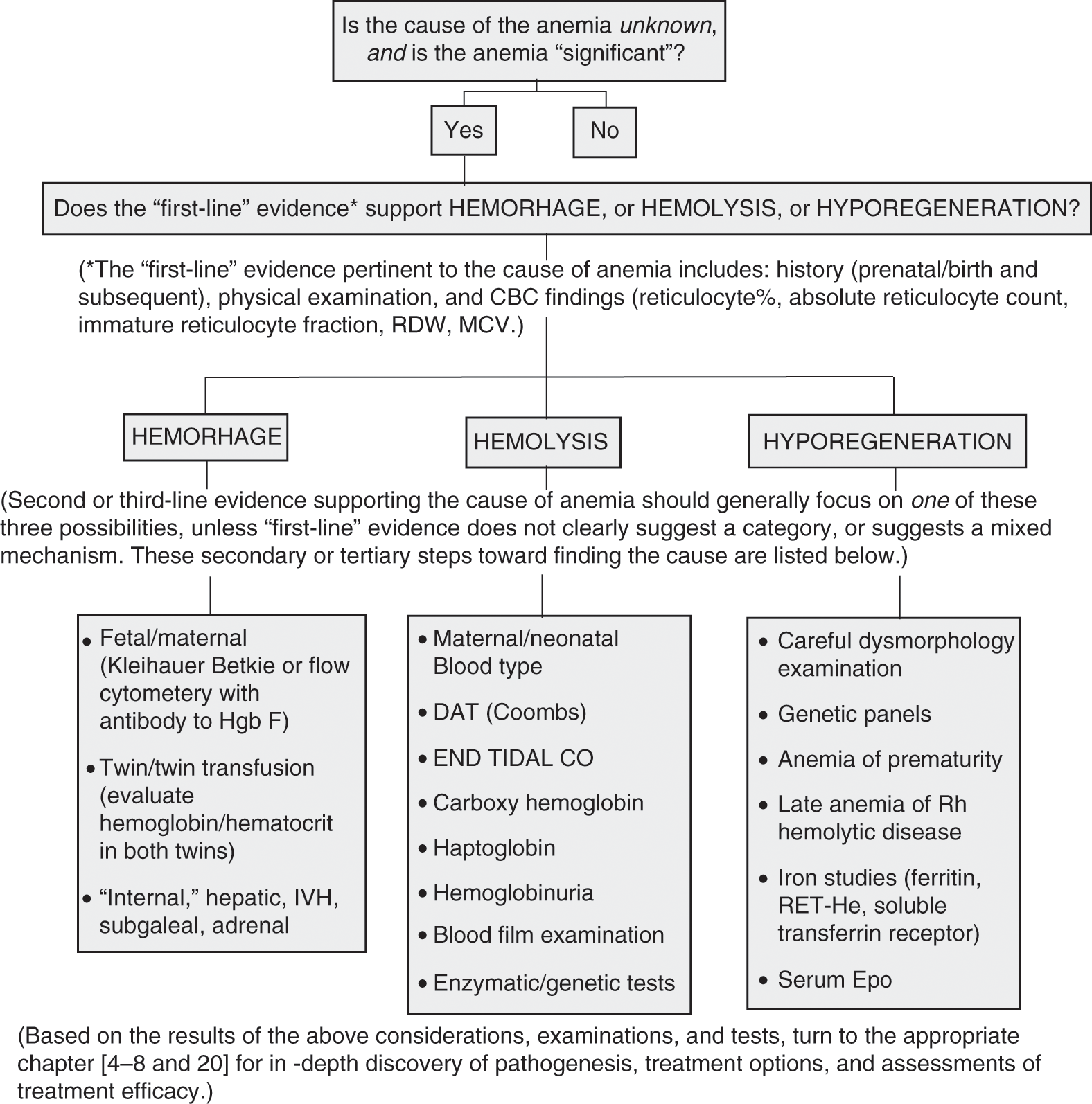

An initial impression of the cause of the anemia often derives from: (1) the history, (2) the physical examination, and (3) the CBC on which the diagnosis of anemia was made. These three elements can be termed “first-line” evidence for discovering the cause of the neonatal anemia, because they are generally readily available at the time the diagnosis of anemia is made. The initial putative cause of the anemia, derived from first-line evidence, can almost always be categorized into one of three groups: (1) hemorrhage, (2) hemolysis, or (3) hyporegenerative (see the algorithm in Fig. 7.2).

Fig. 7.2 Finding the cause of the anemia.

Very rarely, neonatal anemia has a mixed causative mechanism. For instance, hemorrhage and hemolysis can co-exist in an anemic neonate with disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), where internal and external bleeding is significant and brisk hemolysis accompanies microangiopathic schistocytosis [8]. However, generally a neonatal anemia has a single cause and is not due to a complicated combination of nutritional, inflammatory, inherited, and/or neoplastic disorders, as can occur in anemic adult patients. Therefore, after gaining an initial impression of causation from first-line evidence, it can be wise to focus on the one most likely cause (hemorrhage, hemolysis, hyporegenerative). Identifying the most likely one will suggest second-line testing to give confirmation and will lead to specific diagnostic testing where such is appropriate. Focusing the secondary tests on one of the three causative categories will diminish unnecessary testing, thus reducing costs, lowering phlebotomy losses, and saving time. The following sections review second-line tests to consider when focusing on one of the three groups as the cause of the anemia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree