Introduction

This chapter reviews changes in gastrointestinal motor and sensory function associated with healthy ageing, together with what is known about the underlying causes and their clinical significance. Illnesses with gastrointestinal complications that are common in the elderly are also discussed, along with medications that potentially affect gastrointestinal motility. The focus is on the oesophagus, stomach and small intestine, since the oropharynx (Chapter 59, Communication disorders and dysphagia), gallbladder (Chapter 23, Liver and gallbladder) and colon and anorectum (Chapter 24, Sphincter function, and Chapter 25, Constipation) are dealt with elsewhere, as are mucosal functions of secretion and absorption.

Control of Gastrointestinal Motility and Sensation

Patterns of motor activity, involving the circular and longitudinal layers of smooth muscle that extend throughout the length of the gut, are coordinated by plexuses of nerves within the gut wall known collectively as the enteric nervous system. Located in the submucosa (submucous plexus) and between the muscle layers (myenteric plexus), this network contains an equivalent number of neurons (about 100 million) to that present in the spinal cord.1 The intrinsic sensory neurons, interneurons and motor neurons that comprise the enteric nervous system control basic contractile activity such as reflex responses to distension. However, these intrinsic patterns of gut motility are modulated by both extrinsic neural and humoral signals. Central modulation of gut motility occurs via extrinsic sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves, while gut sensation is conveyed to higher centres by both the vagus and spinal afferent nerves, with noxious signals transmitted predominantly via the latter. Descending pathways to the spinal cord modulate the transmission of sensory signals.

Pathophysiology of the Ageing Gut

In rodent models of ageing, there is a substantial reduction in the number of neurons in the enteric nervous system, which becomes increasingly prominent more distally in the gut (40% loss in the small intestine and 60% in the colon, in the myenteric plexus of rats).2 Similar neuronal loss is reported in the oesophagus in older humans, while in the human colon the decline in neuron numbers begins as early as the fourth year, but is most marked between young adulthood and old age.3 Losses are selective for cholinergic neurons and involve both the myenteric plexus (involved with initiation and control of smooth muscle contraction) and the submucous plexus (involved in secretion and absorption and also motor control).4, 5 Nitrergic neurons, which generally mediate inhibitory motor responses, are protected in number but develop axonal swelling and glial cells are also lost in parallel with neurons. Regarding the extrinsic nerve supply to the gut, the number of vagal fibres innervating the upper gastrointestinal tract does not appear to decline in ageing rats, but afferent and efferent fibres undergo morphological changes.4 In particular, vagal afferents associated with both the muscle wall and the mucosa of the gut degenerate with age, potentially compromising both sensory feedback and gut reflexes.6 The underlying causes of neuronal loss with ageing remains unclear, although caloric restriction appears to be protective.7 Recent data also indicate a loss of interstitial cells of Cajal in the ageing human colon;7 these specialized cells are responsible for the propagation of the electrical rhythm of the gut on which muscle contraction is superimposed. Limitations to our understanding of the pathophysiology of the ageing gut include a relative lack of studies relating to the upper gut and the sphincters and the paucity of human data compared with animal models.

The relatively good preservation of gastrointestinal motility in the healthy elderly may imply that the large number of neurons in the enteric nervous system provides a considerable functional reserve, but even this may be limited; transit of a radiolabelled meal through the upper gut occurs at a comparable rate in the healthy elderly and the young, but is slower through the colon in the elderly, where the loss of enteric neurons is greatest.8 It may therefore not be surprising that constipation is the one gastrointestinal complaint that clearly stands out in the elderly compared with the middle aged.7 In the oesophagus, selective loss of intrinsic sensory neurons could explain why contractile activity in response to distension (so-called ‘secondary peristalsis’) occurs less frequently in the healthy elderly than the young.

In contrast to motor function, gut sensation is more consistently impaired with age, as reflected by decreased perception of balloon distension in the oesophagus,9 stomach10 and rectum11 in comparison with young subjects. A selective loss of intrinsic sensory enteric neurons may be responsible. However, the amplitude of cortical evoked potentials recorded from scalp electrodes during repeated oesophageal distension in older subjects is lower than in the young, raising the possibility that altered central processing of signals might also contribute to diminished sensation.12 In addition to mechanical stimuli, perception of chemical stimuli such as acid decreases with age, suggesting a generalized impairment of gut sensation.

Oesophagus

Patients with disordered oesophageal function can present with dysphagia or ‘heartburn’ or less specific symptoms such as chest pain or chronic cough. Age-related changes in oesophageal motility are extensively documented, but probably impact mainly on the very old. Classic oesophageal motility disorders such as achalasia, although uncommon, can present particular challenges in the elderly. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is as prevalent as in the young, often presents atypically and is more likely to be severe.

Changes in Oesophageal Motor Function Related to Ageing

The oesophagus incorporates striated muscle in the upper portion and smooth muscle in the lower, with an upper oesophageal sphincter (UOS) and lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS) at either end. The term ‘primary peristalsis’ refers to the coordinated sequence of contraction associated with swallowing, propagated from proximal to distal oesophagus. The LOS relaxes early in this sequence to allow the swallowed bolus to enter the stomach. ‘Secondary peristalsis’ is triggered by reflux of gastric contents into the oesophagus or experimentally by balloon distension and serves to clear the oesophagus of acid and bile. ‘Tertiary contractions’ represent spontaneous, uncoordinated oesophageal motor activity. While both tonic contraction of the LOS and its position within the diaphragmatic hiatus are important barriers against acid reflux, transient sphincter relaxations, particularly after a meal, are the most prevalent mechanism of acid reflux in most GORD patients. Defences against reflux include neutralization of acid by saliva (which contains bicarbonate), together with acid clearance by primary and secondary peristalsis.

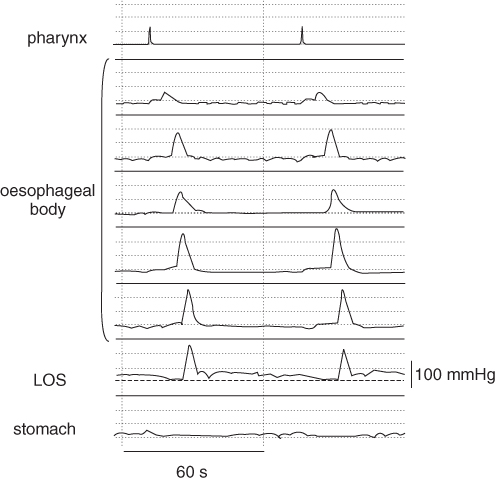

Oesophageal motility may be evaluated by manometry. In this procedure, a catheter incorporating multiple lumens within a relatively small external diameter is passed through the nose or mouth and perfused with water. Each lumen terminates in a sidehole at a different level of the oesophagus and, when coupled to pressure transducers and displayed as recordings of pressure over time, the assembly provides information about the amplitude, duration and propagation of pressure waves (Figure 21.1). Incorporation of either a sleeve sensor or multiple closely spaced sideholes into the assembly is ideal for measurement of both the resting pressure and relaxation of the UOS and LOS. Solid-state transducers, mounted at intervals along a catheter, represent an alternative method of manometry to water-perfused catheters. Multi-channel intraluminal impedance, a technique that records electrical impedance between sequential pairs of electrodes, is emerging as a method of evaluating flow of liquid and air in the oesophagus. While offering new insights into oesophageal function, it has yet to be applied specifically to the elderly. Radiographic imaging of swallowed contrast agent can reveal abnormal oesophageal wall movements (especially cineradiography), dilatation or delayed oesophageal transit. Transit can also be evaluated by the passage of a radiolabelled bolus, imaged by a gamma camera—a technique known as scintigraphy. While endoscopy is most useful in demonstrating mucosal lesions or strictures, it may also provide evidence of abnormal motor activity in disorders such as oesophageal spasm or achalasia.

Figure 21.1 Normal oesophageal manometry recording during water swallows, showing primary peristalsis. The pharyngeal pressure wave indicates the onset of swallowing, which is followed by an orderly sequence of waves from one channel to the next. Note the swallow-induced relaxations of the LOS, whose pressure decreases to approximate intragastric pressure (dashed line).

The effects of ageing have been studied more extensively in the oesophagus than any other gastrointestinal region, reflecting both its accessibility and the importance of swallowing disorders in the elderly. Soergel et al. coined the term ‘prebyoesophagus’ in 1964 when reporting radiological and manometric observations in a group of nonagenerians.13 Only two of 15 subjects had ‘normal’ oesophageal motility and on barium examination there was a high prevalence of tertiary contractions, delayed clearance and oesophageal dilatation. Manometry showed non-peristaltic, multi-peaked pressure waves. These subjects, however, could scarcely be described as healthy elderly, given the high prevalence of dementia and other chronic illnesses, including diabetes. Not surprisingly, more recent studies indicate that the prevalence and severity of oesophageal motor dysfunction in healthy ageing is less than suggested by early reports.14 While there are other reports of oesophageal dysmotility in the very old,15 in subjects aged less than 80 years there appears to be little difference in primary peristalsis when compared with young people, although simultaneous contractions may occur more frequently. The impact of ageing on the amplitude of oesophageal pressure waves may vary by site; distal oesophageal amplitudes increase with age, while a decrease is reported more proximally. Nevertheless, the magnitude of these changes is modest.16 Secondary peristalsis is elicited less consistently by distending stimuli in the healthy elderly compared with the young17 and increasing oesophageal stiffness, together with an increased threshold for perceiving distension, may contribute to this phenomenon.18 In fact, changes in biomechanical properties and primary and secondary peristalsis are observed from as early as 40 years of age.19

In the healthy elderly, while both the length of the UOS high pressure zone and its resting pressure are less than in young subjects, relaxation and opening of this sphincter are delayed.20 The result is a prolongation of the oropharyngeal phase of swallowing and an increase in intra-bolus pressure in the hypopharynx. Although not clinically significant in the healthy elderly, these findings must be taken into account when evaluating swallowing studies in older patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, where the use of reference ranges derived from the young would be inappropriate. Reflex responses of the UOS to oesophageal stimuli (increased pressure with oesophageal balloon distension and decreased pressure with air distension) appear to remain intact with healthy ageing, but reflex UOS contraction in response to laryngeal stimulation is impaired;21 the latter could predispose to aspiration. The fact that only the frequency and not the magnitude of the response is diminished suggests that the sensory side of the reflex arc is impaired.

The elderly have an increased prevalence of hiatus hernia (around 60% of those aged over 60 years)22 and both the resting pressure and intra-abdominal length of the LOS decline with age, while acid exposure increases,23 implying a predisposition to GORD. Other predisposing factors include reduced flow of saliva and impaired acid clearance. The frequency of transient LOS relaxations, the major mechanism of acid reflux in most individuals, has not been specifically studied in the elderly, nor have mucosal repair mechanisms been compared with the young. The number of reflux episodes appears similar in both age groups, but their duration appears to be more prolonged in the elderly;24 this may relate to impaired clearance mechanisms. The refluxate may be less acidic due to a higher prevalence of atrophic gastritis in the elderly, but it should be recognized that its bile content may be important in mucosal injury (e.g. Barrett’s mucosa) and this has not been studied specifically in relation to age.14

Clinical Presentation of Disordered Oesophageal Motility

Disordered oesophageal motor function may present with symptoms of difficulty in swallowing (dysphagia) or chest pain. In both nursing homes (50–60%) and general medical wards (10–30%), there is a high prevalence of dysphagia when patients are specifically questioned,25 although less than half of elderly subjects who reported dysphagia in a population-based survey had consulted a physician about the problem. Potential consequences of dysphagia include aspiration, which contributes substantially to mortality and inadequate intake of nutrition.

Swallowing disorders can be classified into those of oropharyngeal (difficulty initiating a swallow) or oesophageal (impaired transport of swallowed material) origin and these can usually be distinguished with a careful history and examination. The oropharyngeal component of swallowing comprises preparatory (chewing food, mixing with saliva and bolus formation), oral (propulsion of the bolus by the tongue and palate to the pharynx) and pharyngeal (transport through the UOS while protecting the airway) phases. A comprehensive discussion of dysphagia of oropharyngeal origin is included in Chapter 59, Communication disorders and dysphagia.

Potential causes of oesophageal dysphagia are listed in Table 21.1. Key points in the history include whether dysphagia is for solids or liquids, is intermittent or progressive and whether there are associated reflux symptoms such as heartburn.26 Progressive difficulty in swallowing solids is suggestive of a structural lesion, while dysphagia for both liquids and solids is associated with motility disorders. Endoscopy provides a means to visualize and biopsy structural lesions and may be therapeutic (e.g., dilatation of a peptic stricture). Endoscopy and biopsy are also likely to be helpful when odynophagia (painful swallowing) is the presenting complaint and in the patient with dysphagia can help exclude eosinophilic oesophagitis, which is increasingly being recognized even in older patients.27 Barium videofluoroscopy provides complementary information regarding motor function and also structural lesions, and manometry is of greatest use in confirming or excluding a diagnosis of achalasia.

Table 21.1 Oesophageal causes of dysphagia.

| Structural lesions |

|

| Motility disorders |

|

Of the primary oesophageal motility disorders, achalasia, diffuse spasm and nutcracker oesophagus are diagnosed over a wide age range. Although the peak incidence of achalasia is in early to mid-adulthood, a second, smaller peak occurs in the elderly.16 Oesophageal spasm is more commonly diagnosed in people over 50 years of age, whereas non-specific motility disorders are particularly associated with an older population. However, the range of manometric diagnoses in the very old (age 80–93 years) presenting to a clinical motility unit with dysphagia was reported to be broadly similar to that in younger patients.28

Achalasia

Achalasia is an oesophageal motor disorder of unknown aetiology, associated with incomplete or absent swallow-induced LOS relaxation and absence of peristalsis in the oesophageal body. Occasionally, simultaneous oesophageal pressure waves of large amplitude are observed (so-called ‘vigorous’ achalasia). Inflammation of the myenteric plexus is an early histological finding, followed by ganglion loss and neural fibrosis. The condition typically presents with dysphagia for both liquids and solids, although weight loss, regurgitation and aspiration may also be presenting symptoms, particularly in the elderly. Conversely, chest pain is reported less often than in young patients.

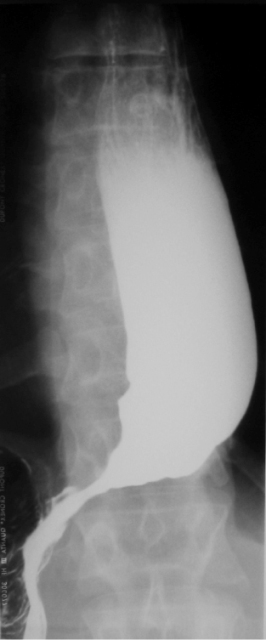

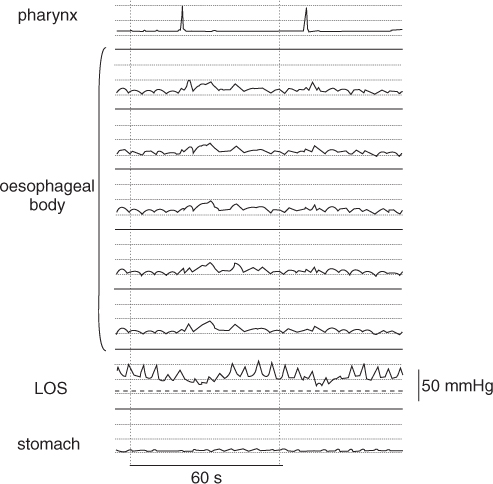

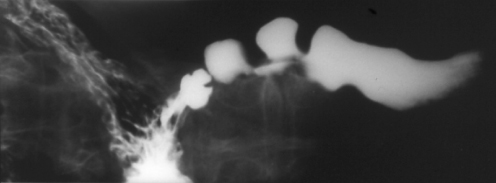

A barium swallow may show impaired peristalsis, delayed emptying and dilatation of the oesophageal body (the latter more characteristic in the elderly than the young), with ‘bird’s beak’ or ‘rat’s tail’ tapering at the LOS (Figure 21.2). At manometry, the resting LOS pressure may be high or within the normal range, but LOS relaxation on swallowing is either absent or incomplete. In the oesophageal body, pressure waves are simultaneous and of small amplitude or absent altogether (Figure 21.3). Endoscopy (and sometimes endoluminal ultrasound or computed tomography) must be performed to exclude ‘pseudo-achalasia’, especially in the elderly; this entity presents with features of achalasia, but is due to carcinoma of the distal oesophagus or cardia. A short history of symptoms and disproportionate weight loss are particularly suggestive of the diagnosis.

Figure 21.2 Barium swallow in a patient with achalasia, demonstrating a dilated oesophagus with tapering at the distal end.

Figure 21.3 Oesophageal manometry in achalasia. Note the simultaneous, small-amplitude pressure waves in the oesophageal body and minimal relaxation of the LOS on swallowing.

Pneumatic dilatation and surgical myotomy (now usually performed laparoscopically) represent the most efficacious treatments for achalasia. Relief of dysphagia after surgery appears as good for older as for younger patients (about 80%),29 while older patients my get better relief from pneumatic dilatation than the young.30 Oesophageal emptying is improved in a smaller percentage and neither therapy addresses aperistalsis of the oesophageal body. Pneumatic dilatation produces controlled tearing of the LOS and is associated with a risk of oesophageal perforation (about 3%) and induction of reflux symptoms (about 10%). Not infrequently, repeat dilatations are required, although two-thirds had no need for further dilatation in a recent report where an initial series of dilatations was guided by their effect on LOS pressures.31 While myotomy may be associated with a greater risk of GORD, it can be combined with an anti-reflux procedure. The lower morbidity of dilatation may favour this procedure over surgery in older patients, with the caveat that a thoracotomy is required if perforation occurs. Pneumatic dilatation is more cost-effective than surgical myotomy.

Endoscopic injection of botulinum toxin into the LOS represents an alternative and safe therapy, but adequate symptom relief may be achieved in fewer patients (around 60%)32 and the benefit lasts around 6 months, so that repeated treatments may be necessary. Therefore, this therapy is best reserved for patients in whom comorbidities represent contraindications to surgery or pneumatic dilatation; this group typically includes the frail elderly. This must be counterbalanced by evidence that the response to both pneumatic dilatation and botulinum toxin is better in older than younger patients. The cost of botulinum toxin injection is slightly greater than that of pneumatic dilatation, but substantially less than that of surgery.

Pharmacological therapy to reduce LOS pressure (nitrates, calcium channel antagonists or sildenafil) is of limited efficacy (possibly even less in the elderly than the young), requires frequent dosing and is associated with side effects.

Patients with achalasia have an increased risk (estimated as 16-fold) of squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus, but the absolute risk is small and surveillance endoscopy has not been advocated.33 Occasional patients have persistent dysphagia despite therapy, together with a tortuous, dilated oesophagus that empties poorly; in these circumstances, oesophagectomy may be required.

Diffuse Oesophageal Spasm and ‘Nutcracker Oesophagus’

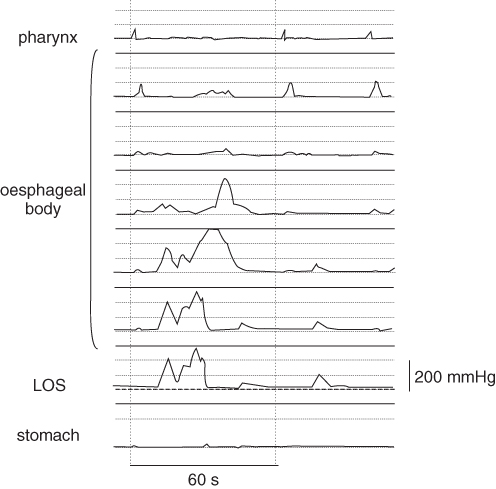

These disorders are diagnosed in a minority of patients with dysphagia or chest pain and in many cases the relationship between symptoms and motor abnormalities is unclear. Criteria for the diagnosis of diffuse oesophageal spasm are inconsistent; the presence of simultaneous oesophageal pressure waves in more than 10%, but fewer than 100% of wet swallows, regardless of amplitude, is a reasonable definition34 (Figure 21.4). The barium swallow may show segmentation of contrast by contractions or a ‘corkscrew’ appearance (Figure 21.5). Similar manometric abnormalities may occur in association with diabetes mellitus, alcohol abuse, amyloidosis, progressive systemic sclerosis and GORD. ‘Nutcracker oesophagus’ is characterized by large-amplitude oesophageal pressure waves, but peristalsis is maintained. The management of both diffuse spasm and nutcracker oesophagus is discussed below, in relation to non-cardiac chest pain.

Figure 21.4 Manometry recording in diffuse oesophageal spasm. Note the simultaneous pressure waves after water swallows, including multi-peaked and large-amplitude waveforms.

Figure 21.5 Barium swallow in a patient with diffuse oesophageal spasm, demonstrating segmentation of the barium column by contractions, producing a ‘corkscrew’ appearance.

Non-specific Oesophageal Motility Disorders

Many patients referred for investigation of symptoms such as dysphagia or chest pain have manometric features that are outside the normal range, but do not meet formal criteria for the diagnosis of disorders such as achalasia and diffuse spasm. In cases where peristaltic waves are of abnormally small amplitude, absent or fail to traverse the whole oesophagus, often associated with a low LOS pressure, a category of ‘ineffective oesophageal motility’ has been proposed.35 Non-specific abnormalities of oesophageal motor function are evident in more than one-third of presentations with dysphagia in patients aged over 65 years, in contrast to the young, where a specific diagnosis can usually be made. It is important to recognize that a causal association cannot be assumed, since the presence of radiographic or manometric abnormalities of oesophageal function correlates poorly with symptoms. Moreover, no specific therapy is available. Symptomatic management includes acid suppression when GORD is a feature and optimizing nutrition.

‘Pill Oesophagitis’

An important cause of dysphagia or odynophagia in older individuals is mucosal injury caused by impaction of medications in the oesophagus, the incidence of which is likely to be increasing as the number of medications prescribed in this group escalates. Risk factors which are more prevalent in the elderly include less saliva, delayed oesophageal transit and immobility. Capsules may present a greater risk than tablets, due to slower oesophageal transit. The most frequent sites of hold-up are the upper and mid-oesophagus, corresponding to extrinsic compression from left main bronchus, aortic arch or enlarged left atrium and also to a zone of small-amplitude pressure waves between the proximal and distal oesophagus. Numerous medications are associated with oesophageal injury, including potassium chloride, tetracyclines, aspirin, non-steroidal drugs, quinidine, theophylline, ferrous sulfate and alendronate.36

Symptoms usually resolve when the offending drug is withdrawn, but may sometimes be persistent and related to stricture formation. Perforation and bleeding are other complications, associated particularly with potassium chloride, quinidine and non-steroidal drugs. The typical endoscopic or barium swallow appearance in pill oesophagitis is of small superficial ulcers. There is anecdotal evidence that sucralfate is beneficial in severe or persistent disease. As a preventive measure, patients should be advised to take oral medications in the upright position, followed immediately by a full glass of water.

Non-cardiac Chest Pain

Chest pain is a prevalent symptom in the community and not infrequently presents a diagnostic difficulty, especially in older patients who are at greater risk of ischaemic heart disease than the young. The oesophagus is often implicated when cardiac causes have been excluded, but musculoskeletal, pulmonary, pericardial, gastric and biliary pathology should also be considered and an association with panic disorder has been reported.37

GORD may be responsible for a proportion of non-cardiac chest pain (NCCP) and about 50% of NCCP patients have excessive oesophageal acid exposure on pH studies. Many patients with excessive acid exposure do not have reflux oesophagitis, which limits the value of endoscopic examination. Rather, a trial of double-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for 2–8 weeks (depending on symptom frequency) is a useful and cost-effective initial test in NCCP, with a sensitivity and specificity as high as 80% each for a diagnosis of GORD. If symptoms are relieved, the dose of medication can subsequently be titrated down to the minimum effective dose. If PPIs are ineffective, then oesophageal manometry and ambulatory pH measurement (while remaining on the PPI) are indicated; the former is particularly helpful for excluding achalasia. Endoscopy should be performed whenever there are ‘alarm symptoms’ such as dysphagia, anorexia, weight loss, haematemesis or anaemia. The threshold for endoscopy in older patients should be lower than in the young (age less than 40 years).

The association between NCCP and oesophageal motility disorders, including diffuse oesophageal spasm and ‘nutcracker oesophagus’, is less strong than previously assumed and even when these disorders are demonstrated, a causal relationship can be difficult to establish, even with 24 h ambulatory manometry.38 Furthermore, medical therapy for oesophageal motility disorders with smooth muscle relaxants such as nitrates, calcium channel antagonists or sildenafil has limited efficacy and surgical myotomy has had only anecdotal success.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree