Challenges to glycaemic control

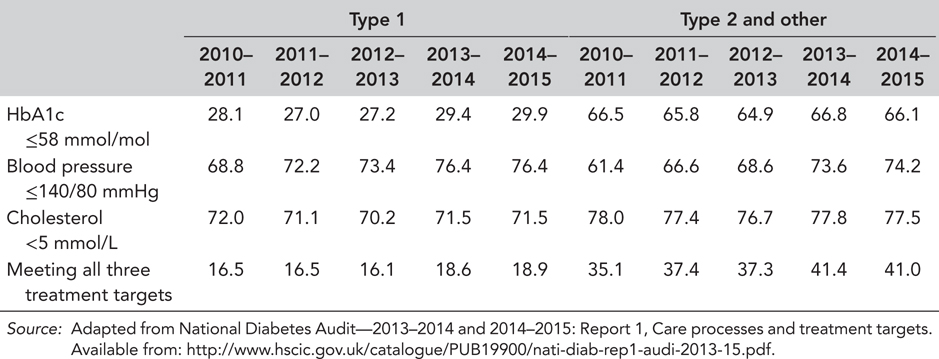

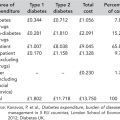

Achieving and maintaining adequate glycaemic control remains a challenge in many people with type 2 diabetes. The most recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend second-line intervention if haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) rises to 7.5% (58 mmol/mol) or higher with a combination of reinforced lifestyle advice and intensified drug treatment. HbA1c treatment targets are personalised, but in general should be 6.5% (48 mmol/mol) for diet ± metformin and 7% (53 mmol/mol) after intensification beyond this (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2015). Statistics from the UK National Diabetes Audit for 2014/2015 indicate that around one-third of individuals with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes in England and Wales have an HbA1c higher than 7.5% (58 mmol/mol) (National Diabetes Audit, 2014/2015) (Table 2.1), a figure that has hardly changed in the past 5 years. The proportion of people with a serum cholesterol level higher than NICE recommendations has remained stable, whereas blood pressure target achievement rates have improved steadily (Table 2.1).

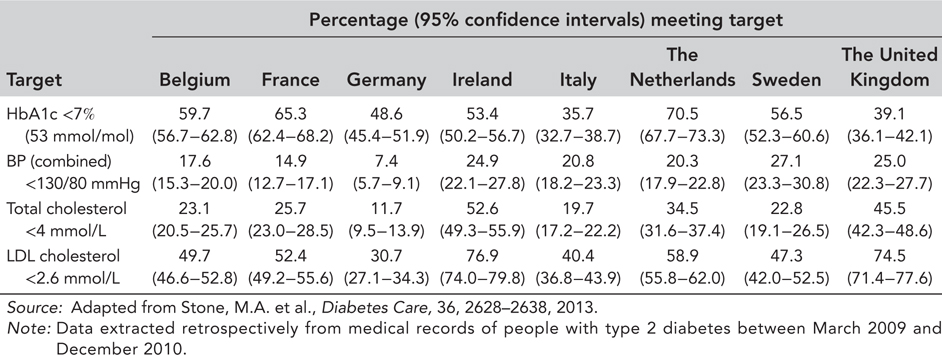

The maintenance of simultaneous control of hypertension, dyslipidaemia and hyperglycaemia is the cornerstone of diabetes care, but this was achieved in only 41% of individuals (Table 2.1) (achievements would have been even less if ‘best practice’ targets had been audited, that is, HbA1c <7% [53 mmol/mol], blood pressure <130/80 mmHg and total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol <4 and 2 mmol/L, respectively). Compared with its European counterparts, the United Kingdom appears better at managing lipids and blood pressure than hyperglycaemia. In a cross-sectional study that examined the medical records of people with type 2 diabetes across eight European countries over the period March 2009–December 2010, the United Kingdom was second lowest in terms of HbA1c target attainment (defined as an HbA1c <7% [53 mmol/mol]) (Table 2.2) (Stone et al., 2013).

Table 2.1 Percentage of people with diabetes in England and Wales achieving their treatment targets by diabetes type and audit year

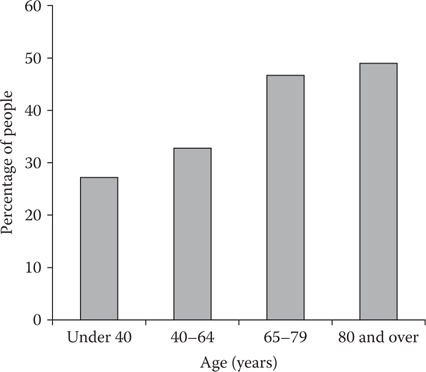

According to the National Diabetes Audit, people aged 65 and over were more likely to achieve simultaneous control of hypertension, dyslipidaemia and hyperglycaemia (just under 50% achieved control) compared with individuals aged 40–64 years old where only a third achieved control (Figure 2.1) (National Diabetes Audit, 2014/2015).

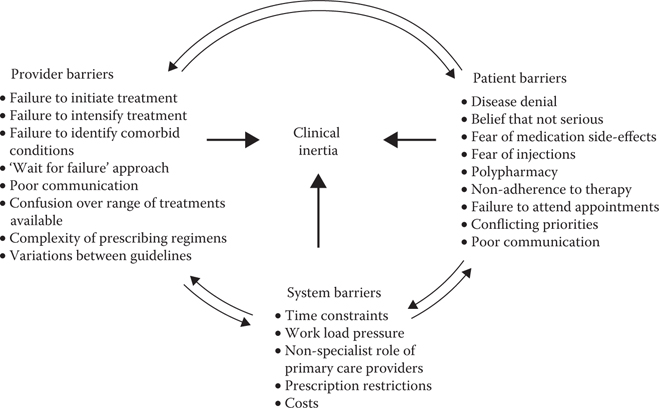

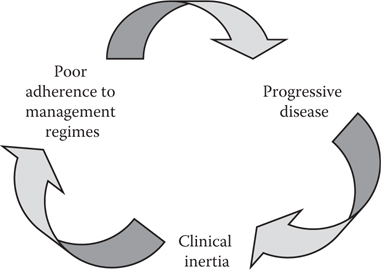

Managing type 2 diabetes appropriately is critical to control its progression and to prevent acute and long-term complications, which are not only detrimental to quality of life and long-term prognosis, but also account for a disproportionate share of the total cost of managing the condition (Liebl et al., 2015). Three main factors continue to challenge glycaemic control: the progressive nature of the disease, poor adherence to management plans and clinical inertia (‘the deadly triad’) (Figure 2.2).

TYPE 2 DIABETES IS A PROGRESSIVE DISEASE

Two major pathophysiological abnormalities underlie most cases of type 2 diabetes: insulin resistance (impaired insulin sensitivity) and β-cell dysfunction. As cells and organs become gradually less sensitive to insulin, the body tries to compensate by producing more insulin, and also by increasing the number of insulin-secreting β-cells. When insulin resistance is accompanied by β-cell dysfunction, failure to control blood glucose levels results. Both abnormalities are essential components of type 2 diabetes pathogenesis, but it is the progressive loss of β-cell function that is central to the progression of the disease.

The management of type 2 diabetes can be considered a ‘moving target,’ in that the underlying pathophysiology is constantly changing and progressing. It is therefore unlikely to respond adequately to any single therapy in the long term, resulting in complex prescribing patterns as the disease progresses with regular adjustments required over time. Furthermore, individuals with type 2 diabetes vary in their levels of insulin resistance and β-cell dysfunction. This has important implications for disease management. For example, the more insulin resistant a person with type 2 diabetes is, the harder it is to manage the disease with agents whose mechanisms of action are insulin dependent because more medication is required to provide enough insulin to achieve target blood glucose levels. The management of type 2 diabetes therefore requires treatment that is personalised to specific glucose (and other cardiovascular risk factors) problems and other health conditions.

Figure 2.1 Percentage of people with type 2 diabetes in England and Wales achieving all three treatment targets (HbA1c ≤7.5% [58 mmol/mol], blood pressure ≤140/80 mmHg and cholesterol <5 mmol/L) by age group, 2014–2015. (Adapted from National Diabetes Audit—2013–2014 and 2014–2015: Report 1, Care processes and treatment targets. Available from: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB19900/nati-diab-rep1-audi-2013-15.pdf.)

Figure 2.2 Challenges to good glycaemic control (all three are intimately interlinked).

Guidelines stress the importance of diet and exercise in the treatment of all stages of type 2 diabetes. These lifestyle measures are cheap and have no long-term side effects, but they demand a high degree of motivation, which will require ongoing support. Many people will require intensification of therapy to oral anti-diabetes agents and the early initiation of combination treatment if glycaemic control is not achieved.

ADHERENCE TO MANAGEMENT PLANS

Reasons for non-adherence are multifactorial and factors may include age, lack of information, perception and duration of disease, complexity of dosing regimen, polypharmacy, psychological factors, tolerability (probably the single most important factor) and, in some countries, cost. Various measures to increase patient satisfaction and adherence in type 2 diabetes have been investigated. These include reducing the complexity of therapy by using fixed-dose combination pills and less frequent dosing regimens, using medications that are associated with fewer adverse events (hypoglycaemia or weight gain), educational initiatives with improved patient–healthcare provider communication and reminder systems. A more detailed discussion of the barriers to adherence and potential solutions is provided in Chapter 3.

CLINICAL INERTIA

Clinical inertia is defined as the failure to initiate or intensify therapy despite an inadequate treatment response and has multiple causes relating to providers, patients and the healthcare system (Figure 2.3). It contributes to inadequate disease care in diabetes as well as a number of other chronic diseases, including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, depression and coronary heart disease. One report states that the contribution of clinical inertia is as likely to cause adverse clinical outcomes as medical errors, the only difference being the time frame in which the adverse event occurs: inappropriate use or misuse of a therapy leading to adverse events in minutes to hours (but may also be much longer, e.g. kidney damage from lithium treatment) and clinical inertia in years to decades (O’Connor et al., 2005). There also appears to be a greater acceptance of clinical inertia by healthcare providers (where the problem is a lack of appropriate prescription) compared with administering inappropriate medication (Strain et al., 2014).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree