CENTRAL AND GONADAL FEEDBACK MECHANISMS IN THE CONTROL OF OVULATION

HYPOTHALAMIC-PITUITARY SIGNALS

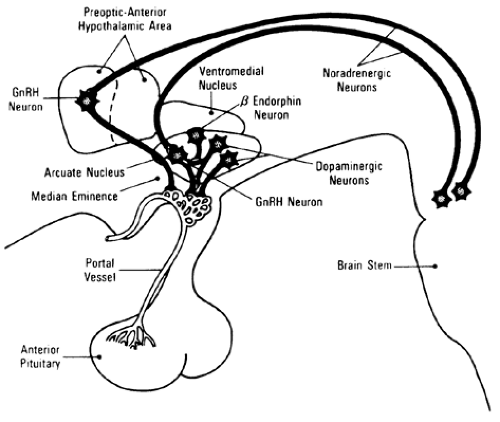

For normal reproduction, the principal hormone that allows gonadotropin secretion from the pituitary gland is the decapeptide GnRH (also known as luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone).21,59 Although GnRH is present in several hypothalamic regions, its greatest concentration is localized to the arcuate nucleus. The physiologic importance of this association is apparent from numerous observations that specific anatomic lesions within the arcuate nucleus result in hypogonadotropic hypogonadism secondary to either the absence of or deficiencies in gonadotropin secretion (see Chap. 8, Chap. 16 and Chap. 96).

GnRH from the arcuate nucleus is transported to the base of the hypothalamus, and more specifically to the median eminence, where it is released into the pituitary portal vascular bed (Fig. 95-9). This relatively closed vascular system directly links the hypothalamus to the pituitary and allows high concentrations of GnRH to affect pituitary gonadotropes directly without systemic passage. Thus, peripheral blood levels of GnRH and the other releasing hormones do not accurately reflect hypothalamic-pituitary interaction. Extremely high levels of GnRH may be present in the portal circulation when peripheral levels are undetectable.60

GnRH-secreting neurons in culture secrete GnRH in a pulsatile manner.61 Furthermore, it is apparent that GnRH must be provided to the pituitary gland in such a pulsatile manner to stimulate normal adult ovarian function and ovulation.62 The requirement for pulsatile GnRH presentation to the pituitary was proved when monkeys with endogenous GnRH secretion eliminated by selective placement of lesions in the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus were given replacement therapy with exogenous GnRH. GnRH given for 6 minutes every 60 minutes effectively induced ovulation and resulted in normal corpus luteum function.21 Continuously administered GnRH was ineffective in inducing ovulation.

From the classic experimental model,21 it is clear that the frequency and amplitude of infused GnRH pulses alter the quantitative secretion of LH and FSH. Continuous GnRH infusion results in less gonadotropin secretion (so-called down-regulation), either because of occupation of all receptors so that stimulation is impossible or because of internalization of receptors such that there is overt refractoriness to stimulation.

Information about responsiveness to exogenous GnRH is being used clinically. With commercially available portable pump technology, exogenous GnRH can be administered at regular intervals (60–120 minutes) either intravenously or subcutaneously over a dose range of 1 to 20 μg per pulse to induce ovulation63,64 (see Chap. 97). Following an initial stimulation of gonadotropin secretion, long-acting GnRH agonists will, within 3 weeks of treatment, down-regulate gonadotropin release, creating a state termed reversible menopause.65,66 and 67 The use of GnRH antagonists has been limited by incidental activation of mast-cell receptors, causing histamine release. Newer-generation GnRH antagonists, however, show great promise, in producing much less mast-cell activation. Down-regulation with GnRH analogs can be used to treat steroid-dependent pathologic processes, including, among others, leiomyomas, endometriosis, hirsutism, precocious puberty, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Future applications of similar technologies may provide new strategies for female and male contraception (see Chap. 104 and Chap. 123).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree