An Optimistic View

The prevalent notion that ‘the older you get, the sicker you get’ often leads the lay public to assume that those who achieve exceptional longevity must have numerous age-related illnesses that translate into a very poor quality of life. Among researchers and clinicians, the observation that the prevalence and incidence of dementia increase with age leads many to assume that dementia is inevitable for those who survive to age 100 years and older.1, 2 For example, the East Boston Study indicated that almost 50% of people over the age of 85 years have Alzheimer’s disease.3, 4 Over the past decade or so, however, significant light has been shed on this assumption, with a number of nonagenarian and centenarian studies addressing the prevalence and incidence of dementia amongst the oldest old; these are summarized in Table 134.1.

Table 134.1 Dementia studies of nonagenarians and centenarians.

| Study | Comments |

| Dutch population-based centenarian study | 10 centenarians in a population of 100 000 people were all noted to have clinically evident dementia.5 Expansion of the study to a population of 250 000 led to finding 15 of 17 centenarians as having dementia6 |

| Swedish population-based study of people aged ≥77 years | The prevalence of dementia amongst the 94 subjects aged ≥95 years was 48% (30% for men and 50% for women)7 |

| Canadian Study of Health and Ageing | Dementia prevalence of subjects aged ≥95 years (n = 104) was 58%. The rate of increase in prevalence slowed at very advanced ages1 |

| Study of Japanese Americans in King County, Washington | Dementia prevalence for subjects aged ≥95 years was 74%8 |

| MRC-ALPHA Study, of older people in Liverpool | Dementia prevalence amongst centenarians was 47%9 |

| Northern Italian Centenarian Study | Dementia was diagnosed in 62% of 92 centenarians10 |

| Finnish population-based centenarian study | 56% of 179 centenarians had cognitive impairment11 |

| Meta-analysis of nine epidemiological studies of dementia among people aged ≥80 years | Prevalence of dementia levelled off at around age 95 years at a rate of 40%12 |

| New England Centenarian (population-based) Study | Cognitive impairment prevalence was 79%13 |

| Danish Centenarian Study | Dementia prevalence was 67%14 |

| Coordinated study of dementia prevalence among centenarians in Sweden, Georgia (USA) and Japan | Dementia prevalences ranged from 40 to 63%15 |

| Heidelberg Centenarian Study | Cognitive impairment prevalence was 75%16 |

| French Centenarian Study | Dementia prevalence was 65% among female and 42% among male centenarians17 |

As most of the studies noted in Table 134.1 indicate, dementia is not inevitable with very old age. Conservatively, ∼15–20% of centenarians are cognitively intact. Furthermore, when dementia does occur, it tends to do so very late in life. In one study, over 90% of the centenarians did not experience functional impairment until the average age of 93 years.18 The Heidelberg Centenarian Study proposed that those who develop dementia at extreme age have a shorter period of functional decline prior to the end of their lives.16 In their review of the neuropathology literature amongst studies of nonagenarians and centenarians, von Gunten et al. concluded that the absence of Alzheimer’s-related pathology in some of these individuals indicates that this disease is not a necessary consequence of ageing.19 There have also been observations by several groups that in some centenarians, there is a disassociation between advanced pathology and clinical presentation, which suggests the presence of functional reserve or some form of adaptive capacity that allows these individuals to do better than expected given the degree of pathology on postmortem examination. The authors conclude that at least some centenarians have some form of resistance to Alzheimer’s disease, the underlying cause of which has yet to be determined. Hence centenarians are of interest in the study of dementia not only for the fact that some of them escape dementia, but also because most of them markedly delay the clinical expression of the disease until very late in their exceptionally long lives.

Compression of Morbidity Versus Disability

The compression of functional impairment towards the end of life that is observed among centenarians would at first glance appear to be consistent with James Fries’s compression-of morbidity hypothesis.20 Fries proposed that as the limit of human lifespan is approached, the onset and duration of lethal diseases associated with ageing must be compressed towards the end of life.21 Although we found that functional impairment was compressed towards the end of life among centenarians, we noted that some centenarians had long histories of an age-related disease. Perhaps an unusual adaptive capacity or functional reserve allowed some of these persons to live a long time with what normally would be considered a debilitating, if not fatal, disease while delaying its attendant disability and death by as much as decades.22–26

Consistent with this observed phenomenon of compression of disability, the Danish Centenarian Study accessed 1997 and 2004 data from the Danish Civil Registration System on nearly 40 000 people born in 1905 and found that centenarians had fewer hospitalizations and shorter hospital stays compared with other members of their birth cohort who died at younger ages. It was concluded that centenarians are a useful cohort for the study of healthy ageing.

To explore this hypothesis in our centenarian sample, we conducted a retrospective cohort study exploring the timing of age-related diseases amongst individuals achieving exceptional old age.27 Three profiles emerged from the analysis of health history data. Some 42% of the participants were ‘survivors’, in whom at least one of the 12 most common age-associated diseases was diagnosed before the age of 80 years; 45% were ‘delayers’, in whom one of these age-associated diseases was diagnosed at or after the age of 80 years, which was beyond the average life expectancy for their birth cohort; and 13% were ‘escapers’, who attained their 100th birthday without diagnosis of any of the 10 age-associated diseases studied. That most centenarians appear to be functionally independent through their early 90s suggests the possibility that ‘survivors’ and ‘delayers’ are better able to cope with illnesses and remain functionally independent compared with the average ageing population. Therefore, in the case of centenarians, it may be more accurate to note a compression of disability rather than a compression of morbidity. As would be expected, this is not generally the case with illnesses associated with high mortality risks. When examining only the most lethal diseases of the elderly, such as heart disease, non-skin cancer and stroke, 87% of males and 83% of females delayed or escaped such diseases (relatively few centenarians were ‘survivors’ with such diseases). These results suggest there may be multiple routes to achieving exceptional longevity. The survivor, delayer and escaper profiles represent different centenarian phenotypes and probably also different genotypes. The categorization of centenarians into these and other groupings (for example, cognitively intact persons or smokers without smoking-related illnesses) should prove useful in the study of factors that determine exceptional longevity.

Nature Versus Nurture

The relative contribution of environmental and genetic influences to life expectancy has been a source of debate. Assessing heritability in 10 505 Swedish twin pairs reared together and apart, Ljungquist et al.28 attributed 35% of the variance in longevity to genetic influences and 65% of the variance to non-shared environmental effects. Other twin studies indicate heritability estimates of life expectancy between 25 and 30%.29, 30 A study of 1655 old order Amish subjects born between 1749 and 1890 and surviving beyond age 30 years resulted in a heritability calculation for lifespan of 0.25.31 These studies support the contention that the life spans of average humans with their average set of genetic polymorphisms are differentiated primarily by their habits and environments. Supporting this idea is a study of Seventh Day Adventists. In contrast to the American average life expectancy of 80 years, the average life expectancy of Seventh Day Adventists is 88 years. Because of their religious beliefs, members of this religious faith maintain optimal health habits such as not smoking, a vegetarian diet, regular exercise and maintenance of a lean body mass that translate into the addition of 8 years to their average life expectancy as compared with other Americans.32 Given that in the USA 75% of persons are overweight and one-third are obese,33 far too many persons still use tobacco34 and far too few persons regularly exercise,35 it is no wonder that our average life expectancy is about 8 years less than what our average set of genes should be able to achieve for us.

Of course, there are exceptions to the rule. There are individuals who have genetic profiles with or without prerequisite environmental exposures that predispose them to diseases at younger ages. There is also a component of luck, which good or bad, plays a role in life expectancy. Finally, there is the possibility that there exist genetic and environmental factors that facilitate the ability to live to ages significantly older than what the average set of genetic and environmental exposures normally allow. Because the oldest individuals in the twin studies were in their early to mid-80s, those studies provide information about heritability of average life expectancy, but not of substantially older ages, for example, age 100 years and older. As discussed below, to survive the 15 or more years beyond what our average set of genetic variations is capable of achieving for us, it appears that people need to have benefited from a relatively rare combination of what might be not-so-rare environmental, behavioural and genetic characteristics, which are often shared within families.

Studying Mormon pedigrees from the Utah Population Database, Kerber et al.36 investigated the impact of family history upon the longevity of 78 994 individuals who achieved at least the age of 65 years. The relative risk of survival (λs) calculated for siblings of probands achieving the 97th percentile of ‘excess longevity’ (for males this corresponded to an age of 95 years and for women to an age of 97 years) was 2.30. Recurrence risks among more distant relatives in the Mormon pedigrees remained significantly greater than 1.0 for numerous classes of relatives, leading to the conclusion that single-gene effects were at play in this survival advantage. The Mormon study findings agree closely with a study of the Icelandic population in which first-degree relatives of those living to the 95th percentile of surviving age were almost twice as likely to also live to the 95th percentile of survival compared with controls.37 Both research groups asserted that the range of recurrent relative risks that they observed indicated a substantial genetic component to exceptional longevity.

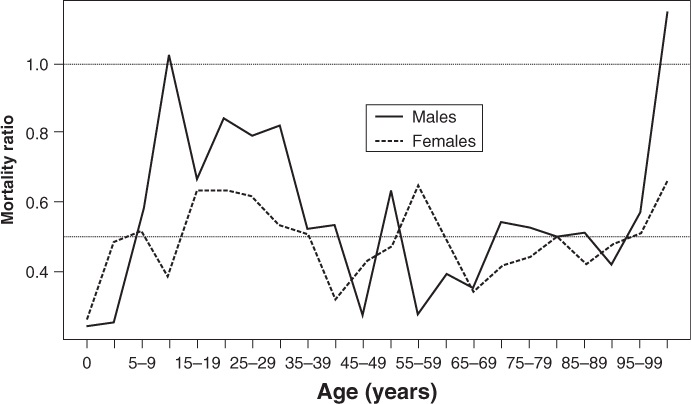

To explore further the genetic aspects of exceptional old age, Perls et al. analysed the pedigrees of 444 centenarian families in the USA that included 2092 siblings of centenarians.38 Survival was compared with 1900 birth cohort survival data from the US Social Security Administration. As shown in Figure 134.1, female siblings had death rates at all ages that were about half the national level; male siblings had a similar advantage at most ages, although it diminished somewhat during adolescence and young adulthood. The siblings had an average age of death of 76.7 years for females and 70.4 years for males compared with 58.3 and 51.5 years, respectively, for the general population. Even after accounting for race and education, the net survival advantage of siblings of centenarians was found to be 16 years greater than the general population. An increasing genetic role with increasing age at very advanced ages is further supported by the work of Tan et al., who noted that the power of a genome-wide association study to discover genes associated with exceptional longevity increases with the age of the subjects, for example from 90s to 100s.39

Figure 134.1 Relative mortality of male and female siblings of centenarians compared with birth cohort matched individuals (controls) from the general American population (survival experience of the controls comes from the Social Security Administration’s 1900 birth cohort life table).

Siblings might share environmental and behavioural factors early in life that have strong effects throughout life. It would make sense that some of these effects are primarily responsible for the shared survival advantage up to middle age. Evidence of effects of early life conditions on adult morbidity and mortality points to the importance of adopting a life course perspective in studies of chronic morbidity and mortality in later life and also in investigations of exceptional longevity.40–47 Characteristics of childhood environment are not only associated with morbidity and mortality at middle age, but have also been found to predict survival to extreme old age.48, 49 Stone50 analysed effects of childhood conditions on survival to extreme old age among cohorts born during the late nineteenth century. Key factors predicting survival from childhood to age 110+ years for these individuals, most of whom were born between 1870 and 1889, were farm residence, presence of both parents in the household, American-born parents, family ownership of its dwelling, residence in a rural area and residence in the non-South; characteristics similar to those that had been previously shown to predict survival to age 85 years.48, 49

In general, however, environmental characteristics such as socioeconomic status, lifestyle and region of residence, are likely to diverge as siblings grow older. Thus, if the survival advantage of the siblings of centenarians is primarily due to environmental factors, that advantage should decline with age. In contrast, the stability of relative risk for death across a wide age range suggests that the advantage is due more to genetic than to environmental factors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree