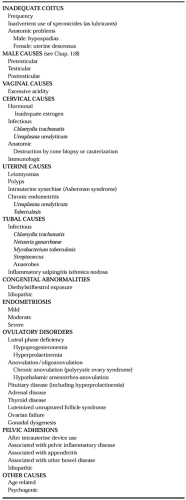

CAUSES OF INFERTILITY

Conception and sustenance of early pregnancy require the integration of all of the steps described earlier. Clinical infertility management is directed toward elucidating abnormalities in reproduction, but many perturbations cannot be assessed directly or corrected, and their relevance to fertility potential is not well established. Nevertheless, several areas of clinical concern can be addressed. Possible causes of infertility are listed in Table 103-1. In general, they include 40% due to the male factor, 40% due to the female factor, 10% due to a combined male/female factor, and 10% due to unexplained causes.

COITAL CAUSES OF INFERTILITY

Optimal fertility occurs with consistent midcycle coital exposure. Although this feature often is taken for granted in an infertility evaluation, establishing that coital technique and frequency are adequate is critical. The optimal frequency of intercourse is every other day during the periovulatory period; more frequent intercourse may lower the sperm count in some men.

Some couples may impair fertility by using lubricants with spermicidal properties. K-Y jelly and Surgilube immobilize sperm in vitro. Rarely, anatomic problems such as uterine descensus or hypospadias in the male contribute to infertility by impeding interactions between sperm and the cervical mucus.

MALE FACTOR IN INFERTILITY

The causes of male infertility are discussed in Chapter 118. Problems of the male partner are estimated to affect 30% to 40% of infertile couples.

VAGINAL AND CERVICAL CAUSES OF INFERTILITY

Putative vaginal causes of infertility that have been proposed include excessive acidity. The normal vaginal milieu is lethal to sperm, and the small fraction of the ejaculate that enters the cervical mucus immediately after ejaculation is the only portion that normally survives. Nevertheless, a deleterious effect of low vaginal pH on fertility and the alleged benefit of alkalinization with sodium bicarbonate have not been documented. Common vaginal pathogens such as Candida, Trichomonas, and Gardnerella vaginalis are not thought to contribute to infertility.

“Cervical factor” infertility remains a controversial entity that encompasses potential infectious, hormonal, anatomic, and immunologic causes. Chlamydia trachomatis and Ureaplasma urealyticum infections may involve the cervix and have been implicated in infertility. Patients with deficient estrogen levels may not achieve optimal cervical mucus production, and sperm migration may be impeded. Ovulation induction with an estrogen antagonist such as clomiphene citrate also may adversely affect cervical mucus and, consequently, sperm migration. Some patients have had surgical excision or ablation of the endocervix or endocervical glands after cone biopsy or cryocauterization of the cervix, with resultant absent or diminished cervical mucus production. The presence of agglutinating and immobilizing sperm antibodies in cervical mucus has been postulated to cause infertility.7,8 Some clinicians use the postcoital test to evaluate the interaction between cervical mucus and spermatozoa, but this test is more of historical interest than of true practical applicability as part of the infertility workup.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree