Cartilage Lesions

Felasfa M. Wodajo

Chondromas

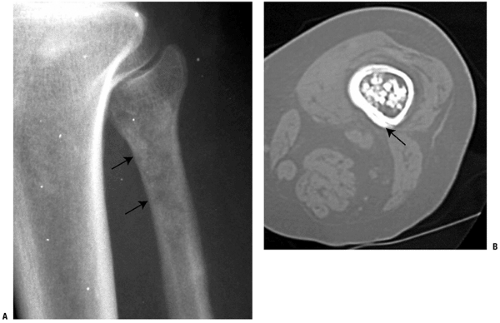

Chondromas, according to the latest World Health Organization classification, include enchondroma, periosteal chondroma, and enchondromatosis. The common thread is that all chondromas are tumors of hyaline cartilage. This distinguishes them from other cartilage tumors such as chondroblastomas and chondromyxoid fibromas, which are tumors of immature cartilage. The tumors of hyaline cartilage share a characteristic pattern of cartilage mineralization, evident radiographically, that allows them to be recognized with a great degree of certainty (Fig. 5.2-1). Enchondroma is the intramedullary variety, periosteal chondroma is the surface counterpart, and enchondromatosis is the congenital chondroma disorder. The latter is described in more detail in Chapter 7, Congenital and Inherited Bone Conditions.

Enchondroma

Enchondromas are benign intramedullary lesions consisting of mature hyaline cartilage. They are common findings in the long bones and are generally asymptomatic.

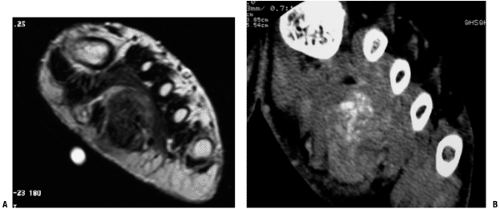

Figure 5.2-1 Soft tissue chondroma in the foot. Large, deep mass with areas of dark T1 signal on MRI (A) corresponding to mineralized portions well visualized on CT (B). |

Pathogenesis

Etiology

Enchondromas are thought to arise from small rests of physeal cartilage entrapped in the metaphysis of growing bones.

Chromosomal abnormalities of 6 and 12 noted in some.

Epidemiology

Frequency: second most common benign chondroid lesion, after osteochondroma

3% to 17% of all primary bone tumors

Autopsy studies: 1.7% of distal femoral metaphyses contain cartilage rests

Most lesions are asymptomatic, and therefore the true incidence is probably higher.

No gender predilection has been noted.

Distribution

Most common location: small bones of hand (40% to 65% of lesions)

Uncommon in distal phalanx

Less common in small bones of the feet

Common in the long bones (25%)

Femur >mt humerus

Solitary enchondromas of flat bones (rib, sternum, scapula): rare

Intramedullary cartilage lesion in these bones should lead to concern for chondrosarcoma.

In the ribs, chondrosarcoma usually at anterior costochondral junction

Solitary enchondromas of the pelvis: very rare

Exception: enchondromatosis

Converse: Chondrosarcoma is relatively common in the pelvis.

Solitary enchondromas of spine: rare

Converse: Chondrosarcoma is the second most common nonlymphoproliferative primary tumor of the spine after chordoma.

Natural History

In general, enchondromas are considered benign, indolent lesions. Slow or no growth is expected. Pathologic fracture through enchondromas in the hands and feet is not uncommon.

Malignant Transformation

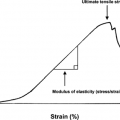

Transformation of enchondromas to malignant chondrosarcoma has been well described (Fig. 5.2-2).

The actual incidence is controversial. Rates of transformation of up to 2% to 3% of large (3 to 7 cm) enchondromas have been suggested.

Atypical or Aggressive Enchondroma (Grade 1/2 Chondrosarcoma; Chondrosarcoma In Situ)

More common than malignant transformation

Painful intramedullary enchondroma that fills the marrow cavity and demonstrates deep (>mt50%) endosteal scalloping

No significant metastatic potential has been described, but they nevertheless should undergo intralesional excision.

Ollier’s Disease (also see Chapter 7.3)

Nonhereditary congenital disease with multiple intramedullary foci of cartilage

Ranges in presentation from asymptomatic enchondromatosis to significant growth disturbances, including bone shortening and deformity

Often unilateral or even single limb in its distribution

Significantly increased risk of secondary transformation to chondrosarcoma, with rates described as high as 5% to 30%

Maffucci’s Syndrome (also see Chapter 7.3)

Another disorder with multiple enchondromas but in association with soft tissue lesions, most commonly hemangiomas

Predilection for hands and wrist

Soft tissue lesions are usually in the same extremity.

Increased risk for developing chondrosarcoma, other sarcomas, and even other, nonskeletal malignancies

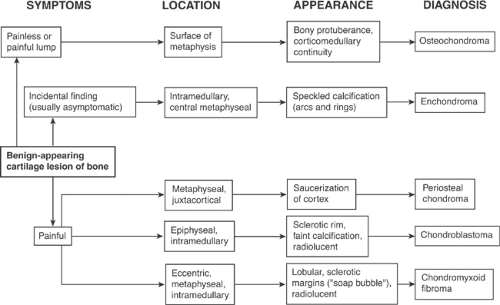

Diagnosis (see Algorithm 5.2-1)

Clinical Features

Most common presentation is as an incidental finding, often in adults undergoing evaluation for other reasons. Often there is a history of knee or shoulder pain. In one series, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated that 81% of patients with proximal humerus enchondromas also had another shoulder disorder potentially causing pain.

Therefore, for patients with vague, nonlocalized pain and in the presence of an enchondroma, therapeutic measures such as steroid injections or physical therapy should be administered for both diagnostic and therapeutic reasons.

Radiologic Features

Radiographs

Long bones

Mineralized central or eccentric metaphyseal or diaphyseal lesion

Punctate rings and arcs mineralization pattern indicative of hyaline cartilage

Large majority (95%) of lesions demonstrate at least partial mineralization.

Typically <6 cm in size, but also sometimes extending for longer lengths (Fig. 5.2-3)

Short tubular bones of the hands and feet

Appearance may be somewhat different

Deep endosteal scalloping

Minimal radiographic mineralization

Well demarcated and sometimes extend to the ends of the bones (see Fig. 5.2-3)

Periosteal reaction and cortical disruption are seen in the setting of pathologic fracture.

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography (CT) is useful for detecting mineralization and extent of endosteal scalloping (see Fig. 5.2-3).

The depth and length of endosteal scalloping have been identified as helpful in distinguishing enchondroma versus chondrosarcoma (Box 5.2-1 and Fig. 5.2-2).

MRI

MRI is useful for determining marrow extent and the presence of soft tissue extension, if any.

The lobular nature of enchondromas is demonstrated well on T2-weighted images (see Fig. 5.2-3).

The dark areas on T1 and T2 represent mineralized portions. However, the value of MRI may be more in diagnosing the source of pain in the patient with a solitary enchondroma discovered incidentally during evaluation of knee or shoulder pain.

Bone Scan

Variable patterns of uptake can be seen on bone scintigraphy.

Some authors have proposed that uptake less than the anterior iliac spine is consistent with the diagnosis of enchondroma.

Box 5.2-1 Objective Signs Worrisome for Malignant Transformation of Enchondromas

Periosteal reaction, cortical destruction, and especially soft tissue extension

Lysis within a previously mineralized area

Deep cortical scalloping, especially greater than two thirds of thickness (see Fig. 5.2-2)

Chondrosarcomas have focal areas of greater than two-thirds scalloping in 90% of cases, enchondromas only 10% of cases

Longitudinal extent of scalloping is throughout the length of the lesion in 79% of chondrosarcomas, as opposed to a shorter extent in enchondromas.

Large unmineralized areas or faint, amorphous calcification

Medullary fill of >90%

Large lesions: 50% of chondrosarcomas are >10 cm

Bone scan radiotracer uptake greater than anterior superior iliac spine

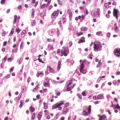

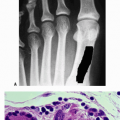

Histologic Features (Fig 7.3-6)

Mature lobules of hyaline cartilage, separated by hematopoietic marrow

Focal myxoid change may be seen.

Long bones: Cartilage should be relatively hypocellular, with only scattered binucleate cells.

Lesions from the hands and feet: Hypercellularity is common, but the diagnosis of chondrosarcoma should almost never be made in those anatomic locations.

Differential Diagnosis

Intramedullary Infarct

Also typically an incidental, asymptomatic finding, but mineralization appears more cloud-like or wispy, without typical arcs and rings calcification of cartilage

It is more common with a history of steroid use or sickle cell disease.

Enostosis

Enostoses or “bone islands” are also asymptomatic, incidental findings, but they have distinctive radiographic and CT findings.

The lesions have dense, ivory-like mineralization and are rarely larger than 2 to 3 cm. The periphery demonstrates a brush-border pattern of trabeculation on CT, and no uptake is seen on bone scan.

Chondrosarcoma

Differentiating between enchondroma and low-grade chondrosarcoma may be difficult (refer to text above and Box 5.2-1).

Cortical disruption, periosteal reaction, and deep endosteal scalloping are associated with more aggressive cartilage lesions.

Treatment

Biopsy

It is difficult to differentiate grade I chondrosarcoma from benign enchondroma by tissue examination alone.

Radiologic and clinical correlation is essential, and therefore biopsy should be reserved for selected chondroid lesions with radiologically or clinically worrisome signs.

Surgical Indications/Contraindications

Observation

Most lesions need no surgery.

On careful search, the pain in the region of the lesion is found to be due to other causes.

Simple follow-up of the lesion initially at 3- to 6-month intervals is indicated.

Pathologic Fracture Treatment

For enchondromas of the short tubular bones that present with pathologic fracture, the phalanx is immobilized until the fracture heals.

If the cortices are thinned such that future fractures are predicted, the enchondroma is curetted and the cavity packed with bone graft or bone cement.

Operative Management

Indicated for painful cartilage lesions that have endosteal scalloping but not periosteal reaction or cortical disruption (i.e., “aggressive” enchondromas or “chondrosarcoma in situ”); intralesional excision is recommended. Some authors recommend the use of physical adjuvants such as phenol or liquid nitrogen to reduce the risk of recurrence.

Intramedullary cartilage lesions of the pelvis are considered malignant and should be resected with wide margins.

Results and Outcome

Recurrence is rare after intralesional excision of enchondromas in the long bones or short tubular bones.

Periosteal Chondroma

Periosteal or juxtacortical chondromas are small, mildly painful lesions of the metaphyseal long bones; the etiology is unknown. They are uncommon and have distinctive radiographic features consisting of a sclerotic saucerization of the cortex and small size. Cellular atypia and hypercellularity are common despite the benign nature of the lesion. Curettage of the lesion is usually curative.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree