Introduction

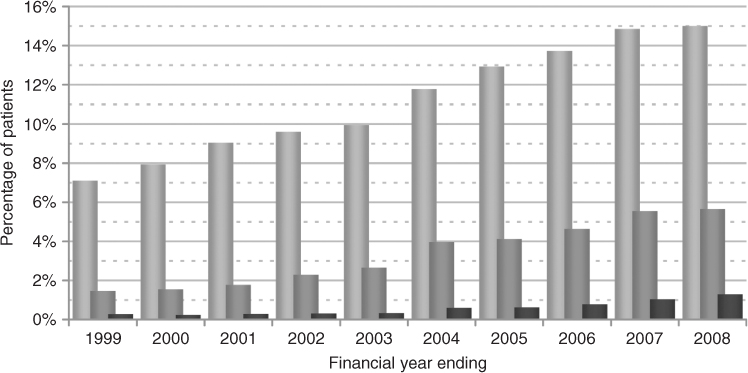

The primary enabling technology that led to the exponential growth in modern cardiac surgery was the development of the heart-lung machine in 1953. Currently, Western economies’ estimated needs are 1000 to 1300 cardiac operations per million population. Life expectancy in Western economies has increased significantly during the past 50 years; in Europe it is now 84 years for women and 77 years for men, and in 2008 approximately 18% of the European population were more than 65 years of age. Moreover, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the elderly,1 and it is estimated that 25–40% of octogenarians have symptomatic cardiac disease.2 Hence the increasing numbers of elderly patients undergoing cardiac surgery (Figure 42.1).3

Figure 42.1 Trends in the relative proportions of older age groups by financial year, of 341 473 patients who underwent heart surgery in the United Kingdom. Age categories are, in increasing shades, 76–80 years, 81–85 years, and >85 years old. Reprinted from Bridgewater et al.3 with permission from Dendrite Clinical Systems Ltd and The Society of Cardiothoracic Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland.

The elderly continue to enjoy an active lifestyle and not unexpectedly want a good QOL, and many feel that a high operative risk, namely death on the operating table is an acceptable alternative to increasing debilitating symptoms in the last few years of life. The decision when to ‘offer’ or ‘deny’ cardiac surgery should though be answered in terms of outcome, mortality and morbidity risk in relation to the expected improvement in QOL. Careful preoperative assessment of comorbid risk factors is also essential in the elderly, because of competing comorbid disease mortality risks.

Cardiac surgery outcome in terms of mortality has continually improved as a result of the development of less traumatic heart-lung machines, more effective myocardial protection strategies, and improved peri-operative care. The mean age of patients undergoing cardiac surgery is progressively increasing and many octogenarians are now successfully undergoing cardiac surgery. In the United Kingdom, 22% of patients undergoing heart surgery were over 75 years of age in 2008 compared to less than 9% in 1999 (Figure 42.1).3

The demographics of the octogenarian or older patient undergoing cardiac surgery differ to that of the younger patient group,4 in that patients are more likely to be female (∼45%), are less likely to have diabetes (∼20%), smoke (∼35%) or have chronic lung disease (∼10%); these observations are possibly indicative that only in the absence of these risk factors is an individual likely to live long enough to become a nonagenarian.

Age per se is not a contraindication for cardiac surgery provided the elderly patient can be discharged without significant disability and loss of independence.

Cardiac Surgery Outcomes in the Elderly

Mortality

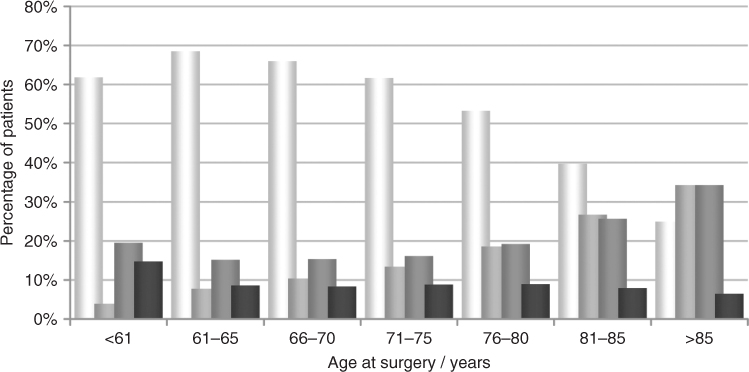

The type of cardiac surgery done is customarily grouped in terms of isolated coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG alone), CABG with concomitant valve surgery (CABG + valve), valve repair or replacement alone (valve alone), and Other procedures. Notably, the type of cardiac surgery done changes in the elderly; isolated CABG is the more common procedure in patients under 75 years of age (64% of heart operations), whilst heart valve operations predominate in patients over the age of 85 years (69%) (Figure 42.2).3

Figure 42.2 Type of cardiac surgery done in 184 461 patients undergoing heart surgery in the United Kingdom during the financial years 2004 to 2008 by patient age-group; isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery (light shade bar), and in increasing shades combined CABG and valve surgery, valve repair or replacement surgery alone, or other procedures. Reprinted from Bridgewater et al.3 with permission from Dendrite Clinical Systems Ltd and The Society of Cardiothoracic Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland.

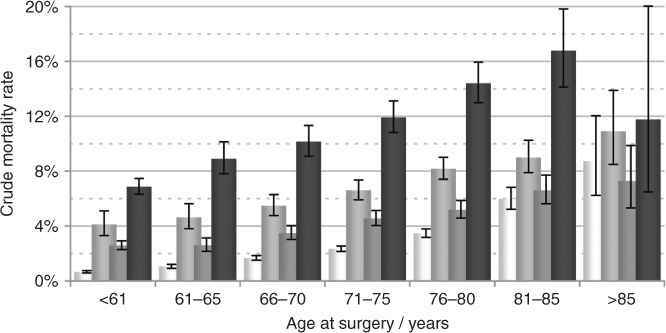

The mortality of cardiac surgery increases with both the complexity of the required procedure as well as with increasing age. Nevertheless, the crude in-hospital mortality associated with cardiac surgery in patients older than 80 years of age has now decreased to approximately 5–9% for isolated CABG, 8–11% for combined CABG and valve surgery, and 5–7% for isolated valve surgery (Figure 42.3).3 The lower aforementioned mortality range figures approximate that for patients electively admitted for surgery from home as opposed to patients undergoing urgent surgery because of the severity of their condition, who have a higher mortality. Nevertheless, elderly patients referred for cardiac surgery almost always have severe disease which if untreated would significantly reduce their life expectancy and result in a worse outcome than the aforementioned mortality rates.

Figure 42.3 Unadjusted cardiac surgery mortality by patient age-group and procedure type in 184 461 patients undergoing cardiac surgery in the United Kingdom during the financial years 2004 to 2008; isolated coronary artery bypass graft surgery (light shade bar), and in increasing shades combined CABG and valve surgery, valve repair or replacement surgery alone, or other procedures. Reprinted from Bridgewater et al.3 with permission from Dendrite Clinical Systems Ltd and The Society of Cardiothoracic Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland.

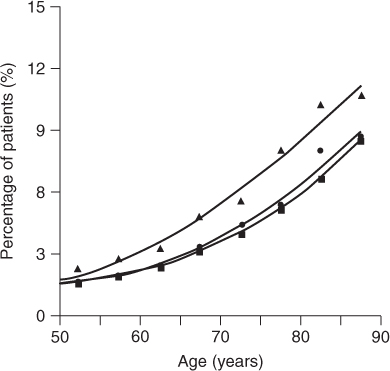

Postoperative complications such as requirement for temporary haemodialysis (incidence: nonagenarian 9.2%, octogenarian 7.7% vs. 3.5% in younger age groups), stroke and prolonged ventilation all increase with age (Figure 42.4).1 The average length of hospital stay following cardiac surgery in patients less than 60 years of age is 9 days but this increases to more than 15 days in patients older than 85 years.3

Figure 42.4 The rate of complications; in-hospital mortality (solid circles), neurological events (stroke, transient ischaemic attacks, or coma; solid triangles), and renal failure (oliguria with a creatinine >1 mg dl−1 or dialysis; solid boxes), by age in 64 467 patients following coronary artery bypass graft, with or without concomitant valve, surgery. Reprinted from Alexander et al.1 Copyright 2000, with permission from Elsevier.

Nonetheless, the expected medium-term post-cardiac surgery actuarial five-year survival in the octogenarian is 60–75%, and with a significantly improved QOL.5

Pre-existing comorbid risk factors associated with increased mortality in octogenarians undergoing open-heart operations should be taken into account when advising patients of the risk of having surgery. These include New York Heart Association (NYHA) dyspnoea class III or IV, female gender, previous myocardial infarction, triple-vessel coronary artery disease, depressed left ventricular ejection fraction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, higher left ventricular end-diastolic pressure, preoperative intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP), congestive heart failure, mitral valve operation, urgency of operation, chronic renal disease, as well as peripheral and cerebrovascular disease.5

Morbidity: Neurological Dysfunction

The postoperative complication of greatest concern following cardiac surgery is a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), which is usually embolic in aetiology. A stroke significantly reduces postoperative QOL and is also associated with a high late mortality following hospital discharge.

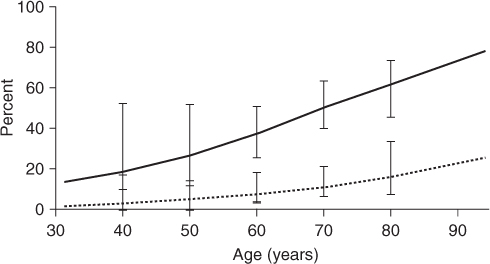

The risk of a peri-operative stroke is higher in the elderly: being 13% in octogenarian compared to 4% in younger patients. Age-related morphological and physiological changes characterized by cerebral atrophy and diminished cerebrovascular reserve capacity, subclinical degenerative brain disease and severe atherosclerosis of the aorta as well as head and neck vessels are multifactor pre-existing comorbid risks contributing to the increased risk of postoperative neurological complications in the elderly (Figure 42.5).6 Intraoperative manipulation of an atherosclerotic ascending aorta increases the probability of atheroembolism and consequent stroke. It is therefore important to identify elderly patients who are at high risk of sustaining a peri-operative stroke preoperatively in order to institute additional intraoperative protective strategies.6

Figure 42.5 Probability of finding atheroemboli in organs, other than the heart or lungs, at 221 autopsies after cardiac operations for ischaemic or valvular heart disease, according to age and the presence of a preoperative history of peripheral vascular disease (solid line) or no history thereof (dotted line). Reprinted from Blauth et al.6 Copyright 1992, with permission from Elsevier.

Preoperative identification of patients with carotid artery disease is important, and our practice is to screen patients at risk for atheromatous disease with carotid duplex imaging (Table 42.1). Carotid artery disease is uncommon in the cardiac surgical patient who does not have coronary artery disease.

Table 42.1 Risk factors for internal carotid artery atheromatous disease.

|

Patients scheduled for cardiac surgery who have coexisting symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid artery disease should then be assessed as to whether carotid artery endarterectomy is indicated either prior to or as a combined procedure with their cardiac surgery. A recent meta-analysis of combined versus staged procedure has shown that in stable cardiac patients the safer option is to perform carotid endarterectomy first followed by subsequent coronary artery bypass grafting.

The presence of severe ascending atherosclerotic plaque at the time of cardiac surgery is associated with a 10% incidence of peri-operative or late neurologic events, compared to 4% in patients with normal or only mild ascending aortic atherosclerosis. Intraoperative mechanisms of identifying ascending aortic atherosclerotic plaque are therefore useful in the elderly; either epi-aortic Doppler ultrasound or transoesophageal echocardiography. If significant atherosclerotic plaque is identified, then reducing ascending aortic manipulation such as off-pump surgery without any manipulation of the ascending aorta, cardiopulmonary bypass using single cross-clamp techniques, and the use of ascending aortic filtration devices are available techniques which can potentially reduce the risk of intraoperative atheroembolism.

More minor neurocognitive dysfunction such as memory loss and changes in visual acuity are also common after cardiac surgery and the aetiology is multifactorial. Pre-existing comorbid neurological risk factors, especially confusional states of indeterminate origin, should, however, be considered relative contraindications to cardiac surgery in the elderly, as undergoing open-heart surgery may aggravate them.

Assessment of the Elderly Patient for Cardiac Surgery

An improved longer-term prognosis is a frequent indication for cardiac surgery in younger patients; however in the elderly, this is less of an issue. Elderly patients must be assessed individually in terms of the natural history of their disease, symptoms thereof, comorbid diseases, current QOL, and the risk (mortality and morbidity) versus benefit (improved QOL) of any potential surgical intervention.

Operative Risk: Estimated Mortality for Cardiac Surgery

Mortality following cardiac surgery usually refers to either in-hospital, that is, deaths occurring within the base hospital during the same admission, or 30-day mortality, that is, deaths within 30 days of surgery. In the United Kingdom, the former definition is currently more commonly used.

Crude mortality fails as a comparative measure of quality between hospitals or surgeons, if there are major variations in case mix. A mechanism of risk stratification based on preoperative factors that increase operative mortality risks, such as age, is therefore essential if referral patterns, allocation of resources, and discouragement of the treatment of high-risk patients are to be avoided. Without risk stratification, surgeons and hospitals treating high-risk patients will appear, on the basis of crude mortality, to have worse results than others.7

The estimated risk of undergoing a given cardiac procedure is therefore determined from known preoperative risk factors and calculating the Euro Score (European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation Score), which is a weighted score that is used preoperatively to provide an estimated predicted operative mortality (Table 42.2).7 The web site http://www.euroscore.org provides a free multilingual risk calculator for predicting cardiac surgical mortality, by both the additive and newer logistic Euro Score.

Table 42.2 Weighted risk factors relevant to a specific individual patient are added and this then provides the Euro Score predicted mortality (%) for that patient to undergo the proposed cardiac surgical procedure (range 0–42%).

| Risk factors and definitions | Weighted-score |

| Patient-related factors | |

| Age (years) | |

| 60–64 | 1 |

| 65–69 | 2 |

| 70–74 | 3 |

| 75–79 | 4 |

| 80–84 | 5 |

| 85–89 | 6 |

| ≥90 | 7 |

| Gender Female | 1 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | |

| Long-term use of bronchodilators or steroids for lung disease | 1 |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy (any or more of following) | |

| History of intermittent claudication, internal carotid occlusion greater than 50% stenosis, previous or planned abdominal aortic, limb or carotid vascular surgery | 2 |

| Neurologic dysfunction | |

| Severely affecting ambulation or day-to-day function | 2 |

| Previous cardiac surgery | |

| Requiring pericardial opening | 3 |

| Renal dysfunction | |

| Serum creatinine greater than 200 μmol l−1 prior to surgery | 2 |

| Active endocarditis | |

| Still under antibiotic treatment for endocarditis at time of surgery | 3 |

| Critical preoperative state (any or more of following) | |

| Ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation or aborted sudden death preoperative cardiac massage, preoperative inotropic or intra-aortic balloon pump support, preoperative ventilation before arrival in anesthetic room, preoperative acute renal failure (anuria or oliguria <10 ml/hour) | 3 |

| Cardiac-related factors | |

| Unstable angina | |

| Rest angina requiring intravenous nitrates preoperatively until theater | 2 |

| Left ventricular dysfunction | |

| Moderate (left ventricular ejection fraction 30–50%) | 1 |

| Poor (left ventricular ejection fraction <30%) | 3 |

| Recent myocardial infarct | |

| Within 90 days of surgery | 2 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | |

| Pulmonary artery systolic pressure >60 mmHg | 2 |

| Operation-related factors | |

| Emergency surgery | |

| Carried out on referral before the beginning of the next working day | 2 |

| Other than isolated CABG | |

| Major cardiac surgery other than or in addition to CABG | 2 |

| Surgery on thoracic aorta | |

| For disease of ascending, arch, or descending thoracic aorta | 3 |

| Postinfarction ischaemic ventricular septal defect | 4 |

| Euro Score Predicted Mortality (%) | |

| Derived by the addition of the above relevant risk factor scores for each individual patient | Σ |

Source: Reprinted from Nashef et al.7 Copyright 1999, with permission from Elsevier

The additive Euro Score has been shown to provide a good correlation with actual observed mortality in the lower-risk groups, but is less accurate and tends to underestimate operative morality when the predicted operative mortality risk exceeds 9%. In the higher-risk groups, the alternative logistic Euro Score mathematical model appears to improve prediction. Although the original simple additive model remains a useful more user-friendly clinical tool to predict immediate operative risk (Table 42.2).

In the future, procedural one-year mortality or more will provide additional useful information for predicting ‘true’ outcome.

Benefit of Surgery: Intended Improved Quality of Life (QOL) Following Surgery

Increased survival is not the primary benefit of cardiac surgery in the elderly and should therefore not necessarily be the primary outcome indicator. Nevertheless, medium-term five-year survival for patients over the age of 80 years is remarkably good; isolated CABG ∼70%, isolated AVR ∼65% and isolated mitral valve repair ∼72%.3

More important is assessing any expected improvements in QOL intended by a proposed cardiac surgical procedure, which is difficult. A perceived improvement in the NYHA dyspnoea score is not sufficient as it does not fully address the broader aspect of QOL and independent lifestyle.

Factors that impact on QOL are mostly physical rather then mental conditions. The SF-36 health survey questionnaire assesses eight general health concepts: physical functioning, bodily pain, role limitation because of personal or emotional problems, emotional well-being, social functioning, energy or fatigue, and general health perceptions. A study of octogenarians who had undergone cardiac surgery showed SF-36 scores equal or better than those of the general population of age greater than 65 years. Moreover, 84–94% of octogenarian operative survivors continue living on their own, and 83–98% indicated that they would in retrospect undergo cardiac surgery again because of the improvements in their lifestyle.8

To date preoperative QOL assessments such as the SF-36 questionnaire have not been used to guide preoperative decision-making. An alternative simpler assessment is the EQ-5D or EuroQol, which assesses the level of mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression, and may well assist in preoperative decision-making (Table 42.3).9

Table 42.3 EuroQol questionnaire, which assesses five quality-of-life dimensions and perception of general and present health state.

| EuroQol questionnaire |

| Mobility I have no problem in walking about I have some problems in walking about I am confined to bed |

| Self-care I have no problems with self-care I have some problems washing or dressing myself I am unable to wash or dress myself |

| Usual activities (work, study, housework, family, or leisure activities) I have no problems with performing my usual activities I have some problems with performing my usual activities I am unable to perform my usual activities |

| Pain or discomfort I have no pain or discomfort I have moderate pain or discomfort I have extreme pain or discomfort |

| Anxiety or depression I am not anxious or depressed I am moderately anxious or depressed I am extremely anxious or depressed |

| Compared with my general level of health over the past 12 months, my health state today is: Better Much the same Worse |

The elderly more frequently have additional coexistent medical conditions, which may frequently worsen, after cardiac surgery. Coexistent medical conditions must therefore be taken into account in terms of the patient’s QOL. Diabetes mellitus with end-organ disease and renal failure are the most hazardous risk factors for a postoperative reduced QOL. Diabetes mellitus results in decreased mobility and chronic pain, whilst renal failure directly affects survival. Care should therefore be taken when selecting patients with those comorbidities for cardiac surgery.

A confounding factor in the assessment of the elderly for cardiac surgery, however, is that suboptimal timing of surgery, namely, excessively late referral for surgery, has a significant negative impact on both operative risk and late outcome.10 The combined effect of delay, deteriorating cardiac status and exacerbating end-organ dysfunction (i.e. renal, pulmonary) may render an otherwise operable candidate beyond salvage.8, 11

The elderly are more sedentary, may not notice milder symptoms, or may attribute symptoms to increasing age and may thus present late. Complete assessment on initial presentation is critical, and mild symptoms in the elderly should not preclude further investigations such as echocardiography and coronary angiography, in order to more accurately determine the presence and extent of any underlying cardiac disease. The decision whether to operate or not should be done without delay and not on a ‘wait and see how symptoms progress’ basis if the best surgical outcome is to be achieved.

Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery

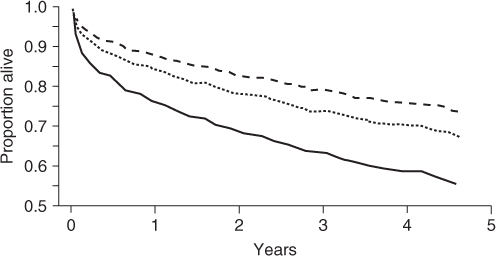

Coronary artery bypass graft surgery forms the majority of cardiac surgery today and was introduced as a therapeutic option in the early 1960s once myocardial ischaemia (angina pectoris or myocardial infarction) was shown to be due to narrowing of the coronary arteries from atherosclerotic plaque. Prospective randomized clinical trials in coronary artery surgery defined the indications for and benefits of CABG in both relieving symptoms and improving survival. These major trials showed that CABG increases survival in patients shown to have left main stem coronary artery stenosis, triple-vessel disease, or double-vessel disease on coronary angiography and in those with impaired left ventricular function or with left ventricular aneurysms. This applies equally in the elderly (Figure 42.6).12

Figure 42.6 Risk-adjusted survival curves for 981 patients, 80 years of age or older, with ischaemic heart disease who underwent either revascularization by coronary artery bypass graft surgery (dashed line) or percutaneous coronary intervention (dotted line) versus continued medical therapy (solid line). Reprinted from Graham et al.12 with permission from American Heart Association, Inc.

CABG reduces the incidence of fatal myocardial infarction, relieves angina, and increases exercise capacity. However, isolated CABG does not improve symptoms of congestive heart failure, especially in the absence of proven hibernating or stunned myocardium.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree