9 Cancers of the thorax

Lung cancer

Aetiology

Environmental and occupational hazards

Other risk factors

Pathogenesis and pathology

Malignant lesions

Box 9.1 shows a classification of lung tumours, which is based on light microscopic assessment of patterns of differentiation. The most important distinction is between small cell carcinoma (SCLC: 15–25% of lung cancers) and other carcinomas, collectively called non-small cell carcinoma (NSCLC). These subgroups behave differently in their presentation, natural history and response to treatment.

Non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC)

NSCLC consist of the following types:

Other neuroendocrine tumours

Presentation

Other symptoms

Paraneoplastic syndromes occur in up to 10% of patients. Box 9.2 lists the paraneoplastic syndromes. SCLC is the most common type associated with paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes. Hypercalcaemia either due to excess parathyroid hormone (PTH) or PTH-related peptides is common in squamous cell carcinomas (15%). Hyponatremia occurs in up to 10% of patients, which is either due to syndrome of inappropriate secretion of ADH (SIADH) or to atrial natriuretic factor. SIADH is commonly associated with SCLC.

Signs

A normal physical examination does not exclude lung cancer.

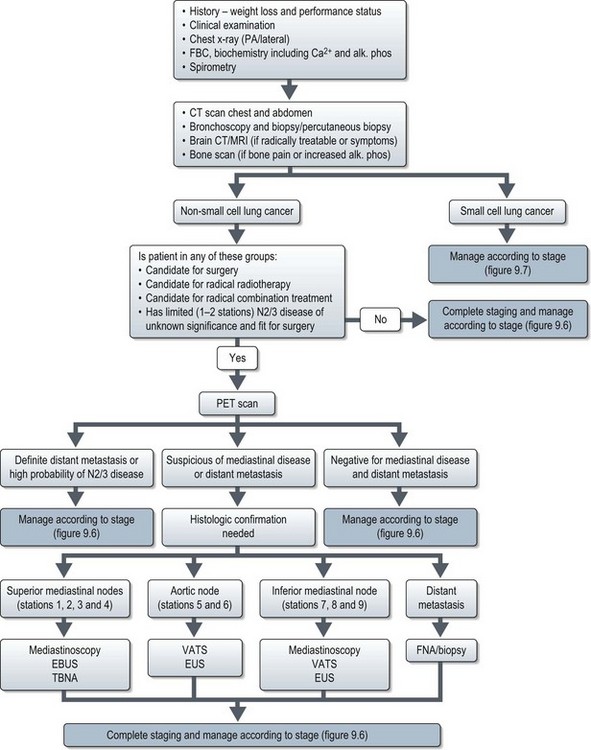

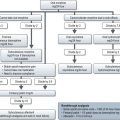

Investigations and staging (Figure 9.1)

Evaluation of a patient with suspected lung cancer is to:

Imaging

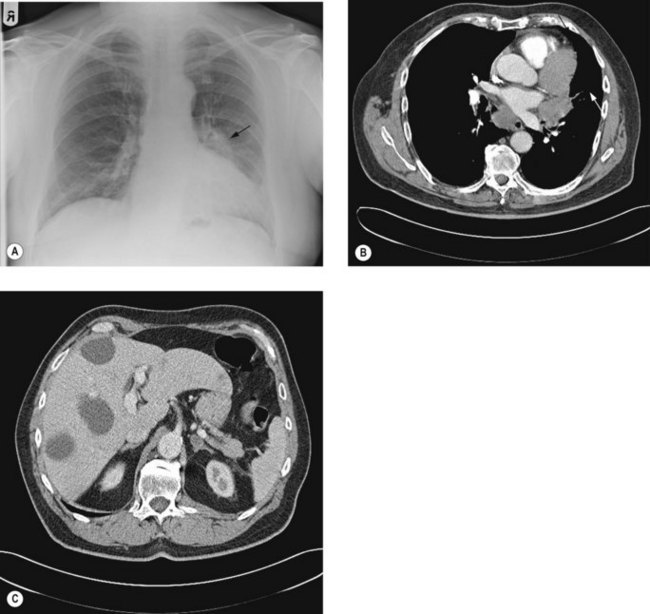

Chest X-ray (Figure 9.2A) may show lung lesion with or without lymphadenopathy. There can be associated lung collapse, pleural effusion, synchronous nodules or pericardial effusion. Bone metastases or bony destruction due to direct invasion can also been seen.

Contrast enhanced CT scan of chest, including upper abdomen (3–10% patients show asymptomatic liver and/or adrenal metastasis – Figure 9.2B&C) should be performed prior to further diagnostic investigations including bronchoscopy.

Bone scan is indicated if there is bone pain or isolated raised alkaline phosphatase.

Staging

Stage determines prognosis and guides treatment. TNM staging of lung cancer is given in Box 9.3. Small cell lung cancer can also be staged using a simple staging classification (Box 9.4). SCLC can be classified as TNM staging or using the simplied.

Box 9.3

Staging of non-small cell lung cancer

Stage Ib

| T2aN0M0 | Tumour >3 cm or ≤5 cm OR |

| Tumour of ≤5 cm with involvement of visceral pleura, main bronchus ≥2 cm distal to the carina or partial atelectasis |

Stage IIA

| T2bN0M0 | Tumour >5 cm or ≤7 cm |

| T1-T2aN1M0 | Metastasis in ipsilateral hilar or peribronchinal nodes |

Stage IIB

| T2bN1M0 | |

| T3N0M0 | Tumour of >7 cm OR |

| Tumour invading chestwall, diaphragm, phrenic nerves, mediastinal pleura or parietal pericardium OR | |

| Tumour <2 cm from carina, atelectasis of entire lung or nodule in the same lobe |

Stage IIIA

| T4N0-1M0 | Tumour invading mediastinal structures or nodule in different ipsilateral lobe |

| T1-3N2M0 | Metastases in ipsilateral mediastinal and/or subcarinal nodes |

Stage IIIB

| T4N2M0 | |

| anyT N3M0 | Metastases in contralateral hilar or mediastinal nodes |

| Metastases in scalene or supraclavicular nodes |

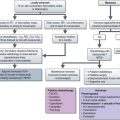

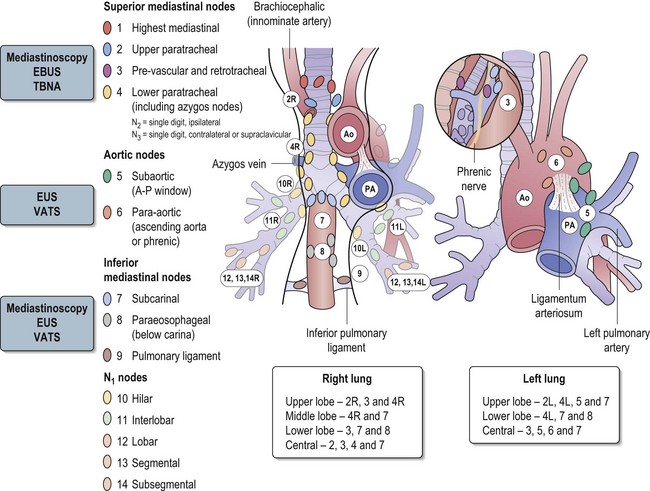

Mediastinal staging in non-small cell lung cancer

Accurate distinction of stages II, IIIA and IIIB is important in deciding optimal surgical treatment in the potentially operable patients. Stage II disease is treated with lobectomy or pneumonectomy with mediastinal sampling or dissection. Stage IIIA disease may be treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed radical surgery or radical chemoradiotherapy, whereas IIIB disease is unresectable. This necessitates both an accurate distinction of T3 from T4 tumours and an accurate staging of nodal status. A classification of mediastinal nodes is shown in Figure 9.3.

Figure 9.3 The classification of mediastinal nodes, patterns of nodal spread and method of choice of staging.

Methods of mediastinal staging

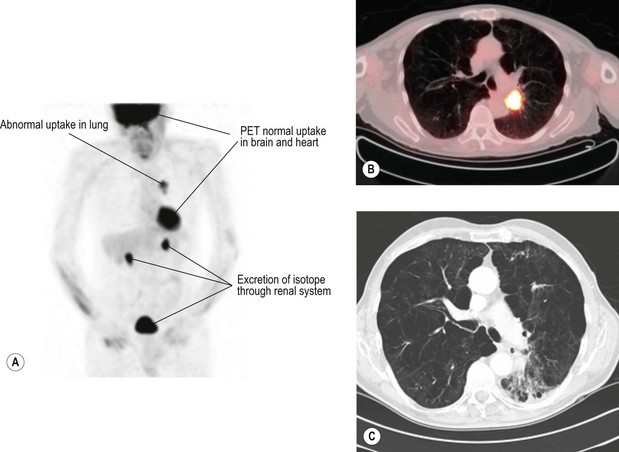

Positron emission tomogram (PET) (Figure 9.4) – PET is scan based on the principle of differential uptake of 2-[fluorine-18]-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) by cancer cells. FDG is metabolized at a higher rate by tumour cells than normal cells and the areas of increased activity can be detected by a scanner. FDG-PET has higher sensitivity (87% vs. 68%), specificity (91% vs. 61%) and accuracy (82% vs. 63%) at detecting mediastinal disease than CT scan. PET also has a high negative predictive value in exclusion of N2/N3 disease, which helps to omit further mediastinal staging in case of a negative PET. Overall, there is 20% improvement in accuracy of PET over CT for mediastinal staging of NSCLC.

One of the limitations of PET is false-positive ‘hot spots’ in the mediastinum due to inflammatory processes (in up to 13 to 17%). It is less accurate when the lesion is <1 cm and in tumours of low metabolic activity such as carcinoid and bronchoalvelolar carcinoma.

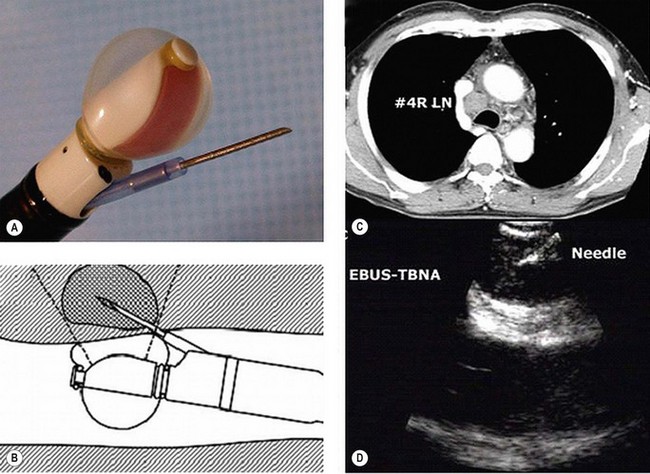

Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) – EBUS is able to penetrate up to 5 cm and can identify lymph nodes and vessels. It is helpful in visualizing paratracheal (stations 2 & 4) and peribronchial lymph nodes (see Figure 9.3) and enables EBUS guided transbronchial needle aspiration (Figure 9.5). Sonographic features of malignant lymph node are round shape, sharp margins and hypoechoic texture. The advantage of EUS over CT and PET is that it can characterize lymph nodes smaller than 1 cm. It can also determine the depth and extent of tumour invasion of tracheobronchial lesions and helps to define the relationships to the pulmonary vessels and the hilar structures. EBUS has been found to predict the lymph node staging correctly in 96% of cases, with a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 100%.

Figure 9.5 Endobronchial ultrasound (A) and its use for FNA (B) of an enlarged lower paratracheal node (C&D).

Mediastinoscopy is generally regarded as the gold standard for preoperative mediastinal evaluation. CT scan is helpful in guiding selection of patients for mediastinoscopy prior to surgery. Cervical mediastinoscopy allows better access to contralateral lymph nodes. It is useful in evaluating paratracheal (2 & 4), scalene and inferior mediastinal nodes (7, 8 & 9). It is not useful in evaluating aortic nodes (5 & 6). Mortality rates from mediastinoscopy are negligible, but morbidity rates especially arrhythmias are reported to be 0.5–1%. It has to be borne in mind that up to 30% of patients with lung carcinoma who have a negative mediastinoscopy prove to have mediastinal nodal metastasis at surgery.

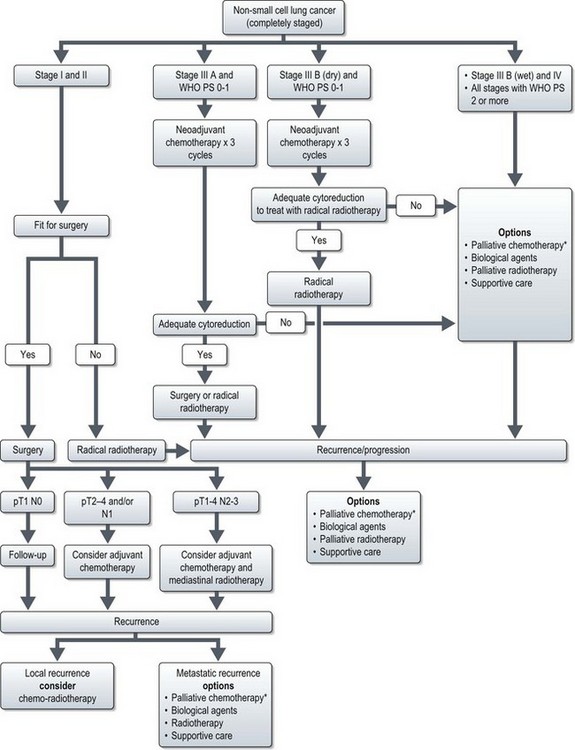

Management of lung cancer

Patients presenting with symptoms suggestive of lung cancer need urgent evaluation (Figure 9.1) and referral to a team specializing in the management of lung cancer. Treatment depends on type of lung cancer (NSCLC vs. SCLC), stage, performance status, co-morbidities and cardiopulmonary reserve.