12 Cancers of the genitourinary system

Cancer of the kidney

Aetiology

Risk factors for renal carcinoma are as follows:

Pathology

Investigations and staging

Imaging

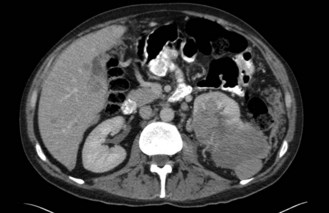

CT scan: CT scan appearance (Figure 12.1) is important in determining the appropriate surgical procedure – laparoscopic, partial or radical nephrectomy. Size is important in diagnosis – benign cortical adenomas can look like malignancies but tend to be less than 3 cm in diameter.

Staging

Stage (Table 12.1) determines the prognosis and treatment of renal tumours.

Table 12.1 Staging of tumours of the renal parenchyma

| Stage | ||

|---|---|---|

| I | T1 N0 M0 | |

| II | T2 N0 M0 | >7 cm in size, confined to kidney |

| III | T1/2 N1 M0 | Confined to kidney, metastases in a single regional node |

| T3 N0/1 M0 | T3a Invades adrenal gland or perinephric tissues but not beyond Gerota fascia | |

| T3b Extends into renal vein(s) or vena cava below diaphragm | ||

| T3c Extends into vena cava above diaphragm | ||

| IV | T4 N0–2 M0 | T4 Invades beyond Gerota fascia |

| T1–4 N2 M0 | N2 Metastases in >1 regional node | |

| T1–4 N0–2 M1 | M1 Distant metastases |

Management

Surgery of the primary tumour

Palliative

Nephrectomy should also be considered as a palliative procedure in patients with metastatic disease. Although very rarely (<1%) this may result in regression of metastases (‘abscopal effect’), it is not the main reason for considering surgery. It is aimed mainly at reducing symptoms such as pain, haematuria and hypercalcaemia. Removal of the tumour bulk may also improve the efficacy of any subsequent systemic treatment – trials have shown that patients with metastatic disease who are treated with interferon have improved survival if they undergo palliative nephrectomy prior to the immunotherapy.

Metastatic disease

Interferon-alpha

Interferon has significant side effects (Box 12.1) that impact on quality of life. These effects are dose dependent, but the majority tend to stop quickly on discontinuation of treatment. Common side effects include fatigue, flu-like symptoms, diarrhoea, nausea and vomiting, anorexia, bone marrow suppression and rash at injection site.

Novel agents

Sorafenib and sunitinib are oral multiple kinase inhibitors affecting VEGF, PDGF and c-KIT tyrosine kinases among others (p. 370). They have both antiproliferative and antiangiogenic activity. A phase III trial of sorafenib versus placebo in metastatic RCC patients on second-line systemic therapy showed an improvement of progression-free survival (5.5 months versus 2.8 months respectively).

Cancers of the urinary bladder and renal pelvis

Aetiology

Risk factors for bladder tumours include the following:

Investigations and staging

Investigations

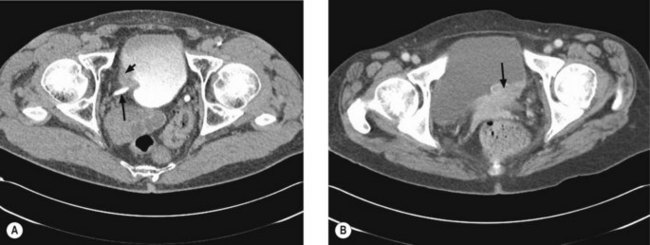

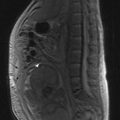

Once a bladder tumour is confirmed further investigations should be considered, including blood tests (renal function, full blood count, liver function and calcium level), chest X-ray, histology review and for muscle-invasive tumours, CT or MRI scan of the abdomen and pelvis (Figure 12.2). MRI is better for showing early invasion of adjacent organs and extravesical spread. A bone scan is only necessary if indicated by symptoms or a raised alkaline phosphatase. Chest X-ray or CT chest is useful to rule out metastatic disease (Figure 12.3).

Staging

The staging of bladder tumours is shown in Table 12.2.

Table 12.2 Staging of tumours of the bladder

| Stage | ||

|---|---|---|

| I | T1 N0 | |

| II | T2 N0 | |

| III | T3 N0 | |

| T4a N0 | T4a – invades prostate, uterus, vagina | |

| IV | T4b N0 | T4b – invades pelvic or abdominal wall |

| T1–4 N1–3 | ||

| M1 | Distant metastases |

Management

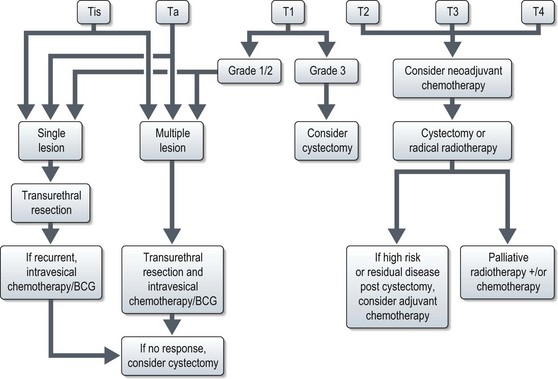

The management of bladder tumours is dependent upon the degree of invasion into the bladder wall and the histological grade of the cancer. Superficial, non-muscle invasive tumours are generally treated by transurethral resection, with intravesical chemotherapy or immunotherapy for multiple or recurrent tumours. Localized muscle invasive disease is treated by primary cystectomy or radiotherapy to the bladder and perivesical tissues. Figure 12.4 shows the management of bladder tumours by tumour stage. Indications for radical cystectomy are shown in Box 12.1.

Intravesical therapy

Muscle invasive disease

Radical cystectomy

Techniques for urinary diversion:

Radical radiotherapy

Radical radiotherapy is typically CT-planned with a target volume including a 1.5–2 cm margin around the empty bladder, prostatic urethra and tumour extension. This margin is to allow for considerable bladder movement. The rectum and femoral heads should be identified as organs at risk. Treatment is usually delivered via a 3-field plan (anterior and two laterals) to a dose of 55 Gy in 20 fractions over 4 weeks or 64 Gy in 32 fractions over 6.5 weeks using 6–10 MV photons.