11 Cancers of the gastrointestinal system

Oesophageal cancer

Aetiology

Box 11.1 shows risk factors for oesophageal cancer. A diet rich in fruit and vegetables has been shown to reduce the relative risk.

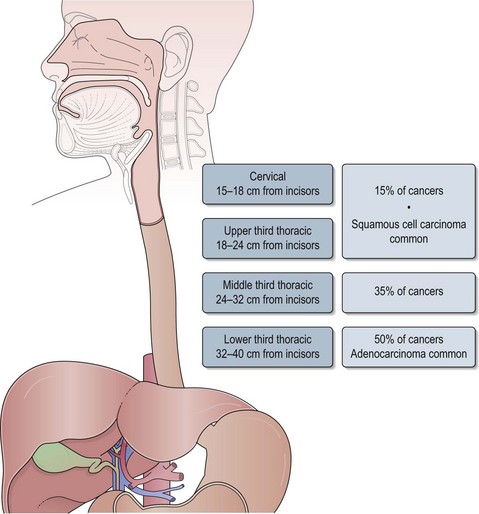

Anatomy

The oesophagus extends from the cricopharyngeal sphincter to the gastro-oesophageal junction (GOJ) and is 25 cm in length. Figure 11.1 shows the anatomic sections of the oesophagus. The majority of tumours (85%) arise in the middle and lower third of oesophagus and 15% arise in the upper third.

Clinical features

Metastatic disease can result in liver capsular pain, bony metastases, ascites or peritoneal deposits. Patients are usually cachectic at this stage.

Investigations and staging

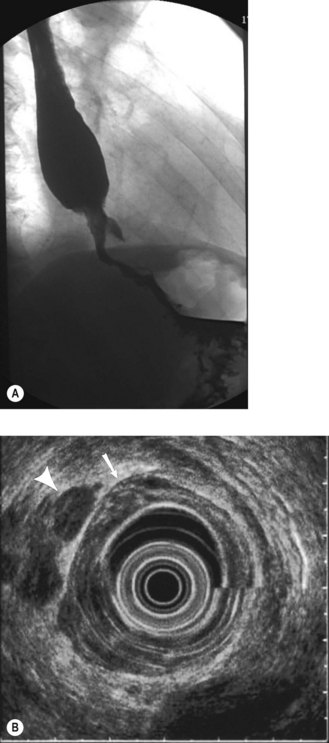

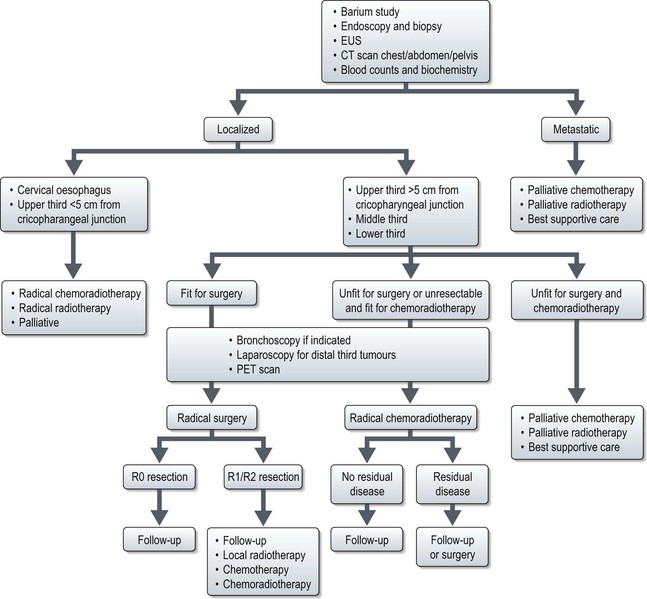

Investigations are aimed at establishing the extent of disease, obtaining histologic diagnosis and assessing fitness for appropriate treatment:

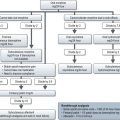

Management of oesophageal cancer (Figure 11.3)

Localized disease

Radical surgery

The common procedures are as follows:

Radical radiotherapy (Box 11.3)

Box 11.3

Radiotherapy for oesophageal cancer

Dose

| Indication | Single phase | 2 phase |

|---|---|---|

| Radical chemoradiotherapy | 50–50.4 Gy in 25–28 fractions | |

| Radical radiotherapy | ||

| Preoperative chemoradiotherapy | 45 Gy in 25 fractions | |

| Palliative | 30 Gy in 10 fractions or 20 Gy in 5 fractions |

Radical chemoradiotherapy (CRT)

Radiotherapy is given in combination with chemotherapy which is proven to be superior to radical radiotherapy alone. Chemotherapy improves local control by radiation sensitization and helps to minimize distant metastatic relapses. This approach results in an overall 3-year survival of 30%. The commonly used combination is cisplatin with 5-fluorouracil with radiotherapy at a dose of 50 Gy in 2 Gy per fraction (Box 11.3). However, locoregional recurrence remains the major cause for overall failure with 50% of patients developing locoregional disease. Attempts to increase the radiotherapy dose to improve local control has resulted in increased treatment-related deaths without improvement in local control or survival. Studies comparing CRT with CRT followed by surgery showed similar overall survival, but with high treatment-related mortality with surgery.

Preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery

A meta-analysis showed that preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery improved 2-year survival by 7% compared with surgery alone (HR 0.90; CI 0.81–1.00). The largest study (MRC OE02) of 802 patients which compared surgery alone with two cycles of 3-weekly preoperative cisplatin (80 mg/m2 on day 1 as 4 hour infusion) and 5-fluorouracil (1 g/m2/day continuous infusion for 4 days) followed by surgery showed that chemotherapy improves overall survival from 34% to 43% at 2-years (p = 0.004). Hence, this is the standard treatment option in most UK centres.

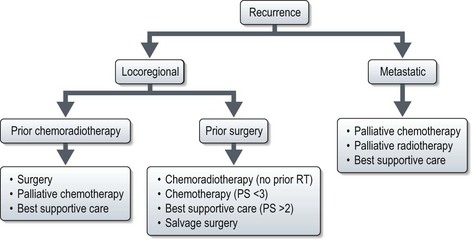

Advanced and recurrent disease (Figures 11.3 and 11.4)

Systemic treatment

Chemotherapy for advanced oesophageal cancer improves survival when compared to best supportive care alone. In the UK, the combination of epirubicin, cisplatin and 5FU (ECF) has been used as the standard regime (Box 11.4). A randomized study (REAL-2) to explore the role of oxaliplatin instead of cisplatin and capecitabine instead of 5-FU (EOX regime) showed that toxicity of 5FU and capecitabine were similar; oxaliplatin resulted in increased neuropathy and diarrhoea but reduced renal toxicity, thromboembolism, alopecia and neutropenia when compared with cisplatin. Patients receiving EOX survived longer than ECF (38% vs. 47% at 1-year; p = 0.02).

Palliative treatment of dysphagia

Gastric cancer

Epidemiology

Only 20% of patients present with localized disease and the overall 5-year survival is 15–20%.

Aetiology

The aetiology of gastric cancer is multifactorial. The following factors increase the risk:

Pathology

Investigations and staging

Further assessment

Staging

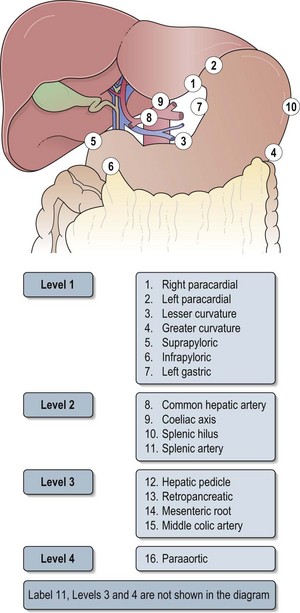

Box 11.5 shows the pathological staging of gastric cancer. Sixteen nodal stations defined by the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer help to define the extent of lymph node dissection in gastric cancer (Figure 11.6 and see below).

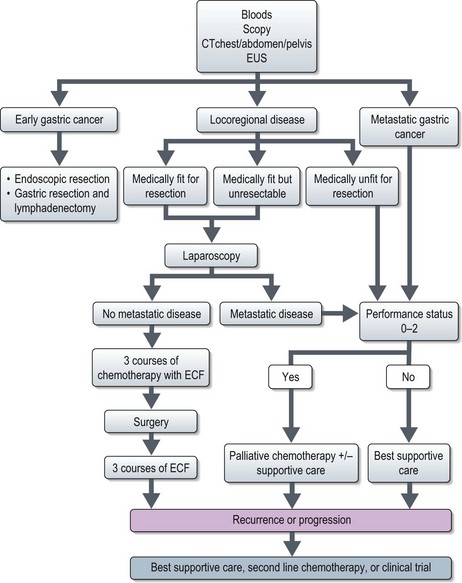

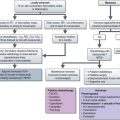

Management of gastric cancer (Figure 11.7)

All patients should be assessed in a multidisciplinary setting. Assessment of the performance status and co-morbidities should be done.

Early gastric cancer (EGC)

Resectable gastric cancer

Surgery

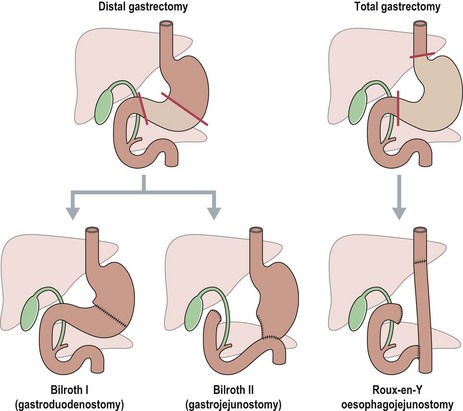

The extent of gastric resection depends on the size and location of the primary tumour (Figure 11.8).

Perioperative treatment

A randomized study (UK MRC MAGIC) showed that three cycles of pre- and postoperative chemotherapy with epirubicin, cisplatin and continuous infusion 5 fluorouracil (ECF) significantly improved 5-year survival (36% vs. 23%; p = 0.009) compared with surgery alone in resectable gastric and lower oesophageal cancers (Box 11.6). This is the standard of care in most of the UK and parts of the Europe (Box 11.6).

Box 11.6

Treatment regimes in gastric cancer

Perioperative chemotherapy and surgery (UK MRC MAGIC trial)

Unresectable gastric cancer

Systemic treatment of unresectable gastric cancer

Patients with unresectable and/or disseminated gastric cancer should be considered for a clinical trial, and those with good performance status (0–2) may be offered systemic therapy. Randomized trials suggest that chemotherapy may improve survival compared with best supportive care (9–11 months vs. 3–4 months HR 0.39) and quality of life. A meta-analysis showed that combination chemotherapy improves survival by 6 months and the best survivals are achieved by three-drug regimens containing 5-FU, anthracycline and cisplatin. The standard regime used in the UK is ECF (Box 11.6). A recent study (REAL 2) showed that ECF is comparable to EOX. This regimen has the advantage of avoiding the need for continuous infusion of 5-FU.